Simon Birmingham is copping flak over funding for Catholic schools

On the vexed issue of school funding reform, there’s a growing view that the Education Minister is being outfoxed by this man.

It was 4.01pm on June 12 when the email headed “Compliance” dropped into Stephen Elder’s inbox. It informed Catholic Education Melbourne’s executive director he was under formal investigation for his schools funding campaign and if he strayed in his responses and the information he provided, he would be jailed for up to one year.

The jail threat was issued twice. Elder was bemused.

“It’s certainly not what I was expecting. I am on solid ground,’’ he tells Inquirer.

At the time the email arrived, Elder had already faced many months of pressure from the Turnbull government over his campaign against its funding model for non-government schools, including false accusations by two cabinet members that he had lied or sought to profit politically from Labor.

But even by the standards of the previous year, the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission email was pushing the envelope. Here was a government entity, albeit independent, threatening the church with criminal sanctions for fighting publicly during a by-election for its schools.

At the same time the Prime Minister is being encouraged internally to restore relations with the church, the ACNC is undertaking a deep dive into the innermost workings of one of the faith’s biggest education commissions.

The ACNC is the nation’s regulator of charities and, as such, has a monitoring role covering organisations such as Catholic education.

The overall education funding debate involves vast sums of cash — total education funding will grow to nearly $250 billion over the next 10 years. But the ACNC investigation is focused on small beer: how $4378.84 was spent by Elder in the March 17 by-election on so-called robocalls for the Melbourne seat of Batman.

In that by-election, Elder had backed a carefully worded, computer-generated phone call to thousands of voters highlighting the key issue of school funding. Labor was facing off against the Greens. There was no Liberal candidate.

The robocalls came soon after Labor leader Bill Shorten had pledged an extra $250 million to Catholic schools in the first two years if he wins government at the next election. The Coalition viewed the calls as Elder’s reward to Labor for the funding commitment, made during the final week of the by-election campaign.

The Elder message stated: “Malcolm Turnbull has slashed funds from low-fee local Catholic and independent schools and our state school system. The Greens seek to strip funds from Catholic schools, threatening your right to choose the best school for your children, putting pressure on the state system. In contrast, Labor believes that local Catholic schools are an essential element of our education system. Labor will restore hundreds of millions in school funding cut by the Liberals to both Catholic and state schools.

“Education is vital for our future — and the future of our schools depends on who you support on Saturday.’’

The message was framed to be factual. The ACNC had flagged in mid-April that it was interested in Elder and the CEM, saying in its opinion “the distinction between political purposes and charitable purposes is one of degree’’.

Bear in mind, Elder’s campaigning on behalf of Catholic schools will net the system potentially billions of extra dollars over the next decade, minus the cost of the robocalls.

The ACNC was specifically interested in the Batman by-election and, as it turns out, the meagre cash that had been spent by the commission, dwarfed as it was by the nearly $16m the government pumped into spruiking its response to the Gonski 2.0 reforms.

Now at stake is the commission’s charity status and tax concessions. The ACNC told Elder: “We consider the expenditure of otherwise charitable funds on an activity is relevant to the question of whether this points to a disqualifying purpose.’’

Somewhere, someone didn’t like what Elder was doing, even though, within three weeks of the latest email lobbing, he was found to be overwhelmingly right in his criticism of the government’s schools funding model.

If you care about freedom of speech, the stakes are amplified when you consider what the ACNC is looking for. It requires CEM to provide its communications strategy, its policies, processes and procedures that explain how political support, lobbying and advocacy was done on the Batman by-election and evidence of any “discussions, considerations or decisions made by the board of directors in relation to the (Batman) campaign’’.

Elder tells Inquirer: “The Catholics didn’t pick this fight with the Turnbull government. But it’s my job to protect the interests of Australian families of modest financial means who want to send their kids to Catholic and low-fee independent schools. Fixing this mess will take money — lots of it. And we will continue the fight until fair funding to the Catholic sector is restored.”

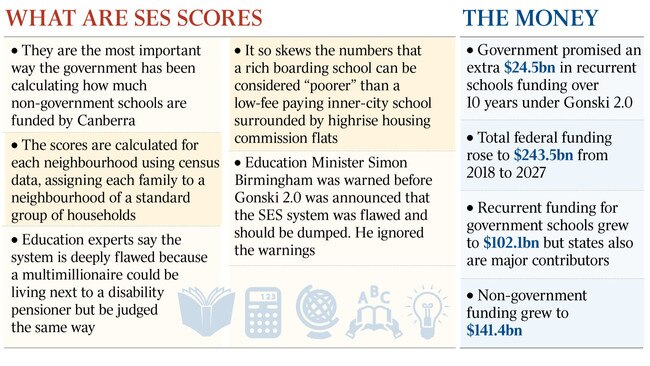

The so-called school socio-economic funding system has been in use since 2001, and for many years the government has been told that it no longer works, with its formula based on where people live rather than a more direct measure such as their income.

The current SES estimates what people can afford to pay based on their neighbourhood. Each family is assigned to a neighbourhood of about 200 households and judged to have the average characteristics of that area, but that means an elite boarding school can be deemed to be poorer than an inner-city Catholic school because rich farmers often live near working class communities.

The flaws are not confined to Catholic schools, with low-fee independents also affected, and the review of the system by businessman Michael Chaney found it was past its use-by date. It was time for a new income-based model, he found, substantially holding up Elder’s arguments.

The conundrum for federal Education Minister Simon Birmingham — not surprisingly, he is no fan of Elder — is that the government has known for many years that area-based SES was a bad measure of parental capacity to pay. But the minister pushed ahead anyway last year with the flawed policy.

He had been reminded weeks before announcing Gonski 2.0 that SES severely disadvantaged the Catholic sector and other low-fee-paying independent schools. Indeed, Turnbull’s friend David Gonski had blown the whistle on the SES funding model in his first inquiry into the education system in 2011.

While Birmingham has rightly been caned for his policy blunder, he has not been alone. Every education minister back to 2011 has failed to act on Gonski’s very clear warning about the SES model.

The first Gonski report confirmed there were some strengths in the SES model but emphatically acknowledged its shortcomings. Gonski found in 2011 that the “area-based SES measure used at present is subject to potentially significant error due to variability in family socio-economic status with census data collections’’.

“This should be replaced in time with a more precise measure that would reflect directly the circumstances and background of each student in a non-government school,’’ he found.

Internally, Birmingham faces a rising tide of anger among Coalition MPs. He has been accused of bungling the government’s relationship with the church, which becomes important during election campaigns and among cash-strapped parents in marginal seats trying to pay school fees.

The church almost begged Birmingham in late 2016 to start proper consultations with it on Gonski 2.0, which was due out in months. The church knew that it was up against it, with Perth Archbishop Timothy Costelloe writing: “On behalf of the 1731 Catholic schools with 766,000 students across Australia, I convey our disappointment that the future of school funding remains uncertain as 2016 draws to a close and that consultation with the Catholic sector has not formally begun.”

Birmingham did meet with the National Catholic Education Commission before Gonski 2.0 was handed down and he told parliament there had been a clear process of engagement across many months. But he conceded there was no attempt to inform stakeholders about the precise funding tools or cabinet discussions (not surprising) before the release of the Gonski 2.0 document.

The Catholic sector still feels ambushed, given it can take years to introduce new funding models and arrangements. To that end, Shorten will soon campaign in on Catholic school funding in Queensland, where officials in the Archdiocese of Brisbane have found a funding hole worth tens of millions of dollars. A hole of $1m or $2m is enough to lead to steep fee increases.

Next week, Turnbull is due to meet the most senior Catholic archbishops in the country. When he does, Birmingham will be called in from an anteroom to discuss the school funding issue. The emergence of the ACNC inquiry into Elder will make that meeting even more awkward.

While Elder’s campaign of opposing the Birmingham policy has been embraced in the church in Victoria, many elsewhere were slow to join the charge, perhaps weakened in confidence because of the sense of crisis that pervades the institution following the sex abuse scandals.

That has now changed markedly and the government has been facing an eastern seaboard backlash from the church and schools, with parents being sent details of how the present Birmingham funding model could affect them.

The risk for Turnbull and Birmingham is the ACNC inquiry will simply embolden the church.

Birmingham’s office did not respond to a series of questions this week from The Weekend Australian, referring instead to the minister’s past statements. He was offered the chance to be interviewed. Birmingham’s office was asked by The Weekend Australian: “Will he be offering an apology when he meets the Catholic archbishops with Mr Turnbull?’’

The PM’s office did not provide an update on when and where the meeting would be held.

But for all the political incompetence Birmingham has been accused of, he has qualified support in the independent schools sector, with its richest schools gaining substantial benefit from his present SES policy.

Internally in the Turnbull government, it’s a different question. There is a growing view that Birmingham has simply been outfoxed by Elder on the politics of funding. Elder, 61, is a former Victorian Liberal MP and the nephew of former premier Sir Henry Bolte.

“Birmingham has been completely smashed on this issue,’’ a senior federal Liberal says.

Following the Gonski 2.0 launch, Birmingham said: “While some lobbyists continue to spread mistruths, I want to reassure parents and families of the simple facts that funding for Catholic schools will increase by $1.2bn over the next four years and $3.396bn over the next 10 years, meaning there is no reason for fees to increase.’’

What Birmingham didn’t say is that the Catholic system, which has more than 1700 schools and more than 750,000 students nationally, would be smashed by an outdated, discredited SES formula. Looking ahead, the independent sector looms as a dark shadow for the government.

Independent schools in Australia are often assumed to be the rich private colleges characterised by rifle ranges and polo fields. Such schools exist. But the majority of independent schools are low-fee-paying schools, with the peak fees ranging between $2000 and $3999, and falling below $2000 at many. At the other end of the spectrum are the very few schools that charge $30,000 or more.

This is the intriguing point of the debate. While Elder, ACT Catholic Education director Ross Fox and Catholic Schools NSW chief Dallas McInerney were stridently defending the Catholic cause, the independents failed to punch through in the public relations war, perhaps because they faced the brick-wall stereotype of rich, white privilege. Or because the existing SES model favours the richest schools.

But when the Chaney review was handed down, the Independent Schools Council of Australia was clear that any response from Birmingham would have to be rigorously trialled and validated.

ISCA does not want to find itself in the same position as the Catholic Church when it was blindsided by Birmingham.

ISCA executive director Colette Colman warned that “significant clarification’’ was needed to ensure sufficient data was available for an accurate assessment of parental need for all schools and wondered whether Chaney’s approach would provide a stable and predictable funding environment.

Her language was conciliatory but clear: “The current approach took three years to model, trial and validate prior to its introduction, and we’d expect the same rigour prior to any move away from the existing arrangements.’’

Education heads were recently told that on one measure, as much as $2bn could be stripped from the independent sector and $1.8bn handed back to Catholic schools. At the same time, the Catholic sector believes it needs $2.5bn to $3bn to restore its finances.

Birmingham, however, won’t be implementing his fix until 2020, when he will probably be long gone from the education portfolio.

Elder, meanwhile, is going nowhere.