Senate repainted shades of Green

THIS will be the first left-wing alliance to control the upper house since 1949.

OVER the past two weeks the 12 outgoing senators who are retiring or were defeated at last year's federal election have been making their valedictory speeches in the chamber before the arrival of 12 new senators on Friday, July 1.

The transition will be significant in terms of personnel and the party complexion in the Senate. That, in turn, is likely to have a profound impact on governance in this, Labor's second term in power.

While Tony Abbott brought the Liberal and National parties back from the electoral brink in the House of Representatives to win more seats than the Labor Party at the 2010 federal election, the same story did not eventuate in the Senate because the half Senate up for re-election was that half elected in 2004, when the Coalition won three of six positions in every state plus a remarkable four out of six in Queensland as part of John Howard's landslide win over Mark Latham. The 2010 Senate result was always going to see the Coalition lose seats.

Despite Howard's defeat at the 2007 election, because the Senate is elected in two halves for six-year terms it continued to provide a powerbase for the Coalition throughout Labor's first term in office stifling, among other things, the government's efforts to legislate an emissions trading scheme.

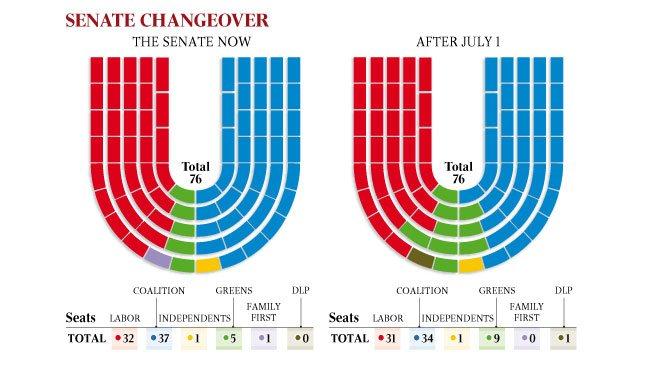

The Coalition holds 37 of 76 seats in the outgoing Senate. That is about to drop to 34 after the results from last year's election. Labor's number of 32 also falls, but by only one.

The big winners are the Greens, with their Senate team almost doubling in size from five to nine, giving the minor party the balance of power in its own right. But that could also cause tensions as Green senators jockey for influence as well as position themselves for leadership positions when Bob Brown -- approaching 70 years of age -- choses to retire.

Sydney University professor of politics and government Rodney Smith notes that while the media identifies the Greens as the new holders of the balance of power, in terms of ideological groupings it is the Labor Party which will in fact represent the balance of power party in the new Senate, juxaposed between the Coalition on the right and the Greens on the left.

"The idea that the Greens have the balance of power is probably the wrong way to look at it," Smith says. "Labor will actually be in a stronger position than most people recognise because it will be able to either play to the centre left or the centre right depending on the issue."

The new-look Senate is rounded out by independent Nick Xenophon, who wasn't up for re-election at the last election, and a blast from the past: the return of a representative of the Democratic Labor Party, which has not won representation at the national level since the 1970s.

John Madigan, a blacksmith by trade, replaces outgoing Family First Senator Steve Fielding, who he beat for the sixth and final spot in Victoria.

Xenophon will have less influence in the Senate courtesy of the new completion of party representation, but his close relationship with lower house independent Andrew Wilkie means it would be a mistake to assume he won't continue to exert influence over the government in policy areas such as gambling reform.

The government needs 39 votes to select a Senate president and pass legislation on the floor of the chamber. As of July 1, Labor and its alliance partner, the Greens, will control 40 votes, the first time a left-wing alliance has controlled the Senate since proportional representation was introduced in 1949. "It is a much easier position than [Labor] has found itself in till now," Smith says.

"Of course that depends on the way the Greens and the Coalition want to play ball."

Labor Senate frontbencher Mark Arbib is taking nothing for granted: "It's always difficult and complex to get your legislation up in the Senate. I don't see it being any easier in the new chamber."

It may be that the formal alliance between Labor and the Greens -- which sees them meet fortnightly outside of sitting weeks, weekly during them -- keeps disagreements between the parties behind closed doors rather than on the floor of the chamber.

Left-wing minor parties have joined with Labor governments before to pass legislation in the Senate, such as when the West Australian Greens held the balance of power during Paul Keating's prime ministership.

But they weren't alliance partners. In fact Keating described the Senate as "unrepresentative swill" at the time, in frustration at Dee Margetts and Christabel Chamarette blocking his legislation.

And while the Greens-Labor alliance has the potential to make dealing with the new Senate easier for the government than the outgoing one, the Greens are not a homogenous disciplined political party, and Julia Gillard still has to deal with her minority government status in the House of Representatives, which requires her to cobble together votes from two

rural independents, a Tasmanian independent and a single Victorian Green to even get legislation before the Senate.

Smith agrees that the lower house will continue to present challenges for the government.

But he suggests that despite the disparate forces within the Greens Senate line up, from environmentalists such as Christine Milne to social justice activists such as incoming senator Lee Rhiannon, they will likely vote as a block, making the party more professional to deal with.

"There has to be that level of trust when negotiating with other parties," he says. He notes that in the NSW parliament, where Rhiannon didn't always see eye-to-eye with her fellow Greens MLCs, the party nonetheless voted as a block on most issues.

There is little doubt the Coalition plans to use the arrival of a radical campaigner such as Rhiannon to damage the Greens and its alliance with Labor.

"I'll tell you something that encapsulates what the new senate will look like. Two words: Lee Rhiannon," Nationals senator Barnaby Joyce says. "It's a startling throw-back to the Cold War."

So far as the main policy issue of this term is concerned, the carbon tax, the new Senate line up will make Gillard's job of legislating for a price on carbon easier than it otherwise would have been.

This is vital to her sales pitch for the next election. Labor needs the tax legislated and implemented to prove to voters that Abbott's scare campaign is over the top if it is to have any chance of winning a third term in office.

"The Greens may want to compromise more this time around than last time," Smith says. "They may not want to be presented as the wreckers." If he is right it will be welcome news to Gillard, who needs to show that the alliance entered with the Greens after the last election is capable of providing stable government.

In terms of incoming and outgoing personnel involved in the Senate transfer, there are some significant names in the mix.

Rhiannon and Fielding have already been mentioned.

There is also outgoing senator Nick Minchin. A former Howard minister and leader of the government and the opposition in the Senate, Minchin was instrumental in securing Abbott his narrow win over Malcolm Turnbull and Joe Hockey in the Liberal leadership showdown near the end of 2009.

A noted climate-change sceptic who used his valedictory speech to affirm that position, Minchin opposed Turnbull's support of Kevin Rudd's ETS, and wasn't willing to support a Hockey bid for the leadership after he called for a conscience vote on the issue.

Minchin surprised some when he announced his retirement shortly after Abbott became leader. He is believed to have grown increasingly disillusioned with the lack of a robust policy agenda being embraced by the Opposition.

Other interesting departures for the Coalition include Julian McGauran and Judith Troeth.

McGauran was a vocal critic of Turnbull during Turnbull's stint as Liberal leader. He was defeated in the number three position for the Coalition in Victoria.

Prominent Liberal moderate and fellow Victorian Troeth chose not to recontest her position at the last election. She crossed the floor in support of the ETS that included Turnbull's amendments after he was defeated for the leadership.

Troeth used her valedictory speech last Wednesday to encourage Liberals to be prepared to cross the floor on issues they feel passionate about.

On the Labor side, two senior members of the Right faction are departing: Senators Steve Hutchins and Michael Forshaw, a former NSW party president and parliamentary convener of the Right respectively. Hutchins was defeated in the normally relatively safe number three position on the ticket while Forshaw didn't recontest at the election.

Both men were early movers against Rudd's leadership after they felt he had stopped listening to the caucus. Six of the 12 senators joining the parliament on July 1 are women (three Greens, two Labor and one Nationals).

One is a former member for Wakefield in the House of Representatives (Liberal, David Fawcett), another is a former state secretary of the NSW Labor Party (Matthew Thistlethwaite).

As is often the case within the main parties, the new senators have strong party organisational backgrounds.

The incoming Greens -- who will be so important to the government's chances of achieving legislative outcomes -- include a mix of lawyers, a healthcare specialist and Rhiannon, who has state parliament experience.

All that's left is to see how the new Senate operates within the confines of the new parliamentary paradigm.

Greens deputy leader Christine Milne, who has experience holding the balance of power at state level in Tasmania, says the Greens are looking forward to their expanded representation.

"That is what the Australian people voted for last year, and I think we have demonstrated already with shared balance of power that we take it very seriously and legislate in a very responsible way. And we intend to keep doing that."