Same-sex marriage opponents tongue-tied by the ‘thought police’

Transgender activist Martine Delaney was reared a Catholic, transitioned to becoming a woman 14 years ago and is now in a same-sex relationship rearing a child — so she is used to her views clashing with those of the church.

But after complaining to the Tasmanian Anti-Discrimination Commission about an anti gay marriage booklet distributed by Catholic bishops, Delaney finds herself at the centre of a national debate about the clash between anti-discrimination laws and free speech.

The complaint has sparked concerns among religious groups and free-speech advocates that anti-discrimination laws will be used to silence the no campaigners in the lead-up to a promised national plebiscite on same-sex marriage.

Australian Christian Lobby managing director Lyle Shelton says the conflict between anti-discrimination laws and the right to freedom of speech and religion has been an issue of “longstanding concern” to his organisation, and one it has raised with government across many years.

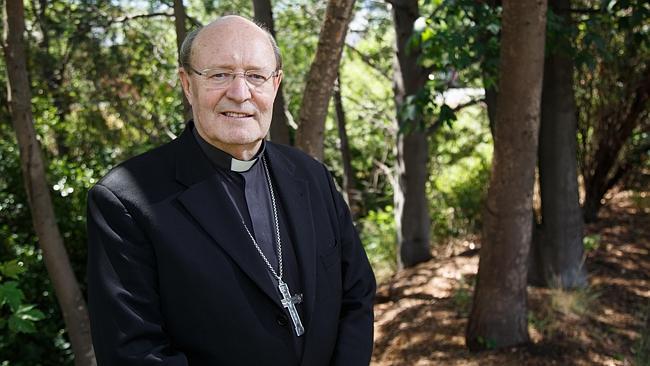

He says the complaint lodged by Delaney, who is a federal Greens candidate, against Archbishop of Hobart Julian Porteous and other Catholic archbishops, is the “realisation of those concerns”.

“We are seeing the Greens political party … actually using the big stick of the law to silence debate,” he says.

“This is totalitarian, this is not free speech. People don’t have to agree with us but most Australians would think at least our side of the debate deserves a fair go, not to use the law to bludgeon us into silence so we can’t get our message across on a matter of important public discussion.”

Shelton says many in favour of retaining a traditional definition of marriage simply take the view that it’s easier not to engage in the public debate.

“We need to have a public discussion about the consequences of redefining marriage and I know that many people on our side are reluctant to speak publicly,” he says.

“For a start, no one wants to be called a bigot or a hater, which is the way you’re immediately characterised, and then in addition to that is the constant threat that you might find yourself in front of an anti-discrimination commissioner.”

Human Rights Commissioner Tim Wilson has criticised the Tasmanian legislation for over-reaching and imposing “soft censorship” on society — although Premier Will Hodgman has flagged a review of the law since the state’s Anti-Discrimination Commission determined that the Catholic Church had a case to answer in relation to Delaney’s complaint.

But Wilson believes the Tasmanian law is unique and that there is less of a risk of similar complaints being lodged elsewhere in the lead-up to the marriage plebiscite.

The state is the only jurisdiction to ban any conduct that “offends, humiliates, intimidates, insults or ridicules” on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity.

“Other laws set a much higher standard or don’t cover sexual orientation at all so therefore you’re far less likely to see these types of complaints,” he says.

“The Tasmanian law is much broader and restricts freedom of expression more strongly and that’s why it was always likely to happen there when you have this type of law.”

NSW, Queensland and the ACT all set a high bar for vilification on the grounds of sexuality, banning only speech that incites “hatred”, “serious contempt”, or “severe ridicule”.

Other jurisdictions — the commonwealth, Victoria, Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory — do not cover vilification on this ground at all, but ban discrimination on the basis of a person’s sexuality in the workplace, education and other spheres.

Australian National University legal professor Simon Rice says it may be possible to try to mount a complaint similar to Delaney’s under those discrimination laws but to do so would be a “stretch”. He says before sexual harassment was specifically outlawed, discrimination laws were used to complain about sexual harassment.

Similarly, he says, discrimination laws could possibly be used in this context.

“It’s possible that in other states you could make a discrimination complaint for this kind of conduct,” he says. “But it’s going to be a narrower, less arguable case.”

Rice is doubtful Delaney’s complaint will be upheld because he believes it could fall within an exemption for acts done in good faith and in the public interest.

He shrugs off concerns about the hardship of being dragged before a commission and the “chilling” impact of these laws on free speech.

“The idea of legislation is to make people think twice about what they do in case it’s contrary to public standards,” he says.

“What is happening at the moment in Tasmania is very low key. Nobody has to have lawyers and usually they’re discouraged from having them.

“All that is happening is the commissioner is saying, ‘Let’s sit around a table and talk.’

“That characterises discrimination law everywhere. The whole ‘oh my god I’m getting dragged into court’ is overstating the very gentle way that discrimination law works.”

But hardline Catholic conservative Bernie Gaynor says only someone who has not been hauled before a commission could dismiss the impact of the process in that way.

The former army major, who prides himself on voicing the opinions that “normal men dare not speak out loud” and was suspended from Katter’s Australian Party for saying he would not let gay teachers educate his children — has become the subject of a flurry of complaints to the NSW Anti-Discrimination Board.

At last count, Gaynor has been the subject of 28 complaints during the past 18 months — all lodged by one man, Sydney gay rights activist and serial litigator Garry Burns. So far, none of the complaints has been substantiated but 10 remain before the board and Burns has lodged an appeal against those dismissed by the NSW Civil and Administrative Tribunal.

Gaynor, who is now a political candidate for anti-Muslim party the Australian Liberty Alliance, says he has had to fly to Sydney from his home town of Brisbane at least 20 times since May last year and has spent more than $50,000 in legal fees fending off the complaints.

“I am winning the legal battles at the moment, but the process is the punishment,” he says.

Gaynor believes the system encourages individuals such as Burns to lodge complaints. He says this is because complaints are free to lodge and there are no costs orders imposed against unsuccessful complainants. He says that soon after he received the first complaint he received a letter from Burns offering to settle the matter confidentially if he agreed to pay $10,000.

“There is no risk to the person lodging these complaints,” he says. “The NSW tribunal has the power to impose a penalty of up to $100,000 per complaint and that penalty goes to the person who lodges the complaint.

“So you have a legal system that is designed to generate complaints.”

Burns, who describes himself as an “anti-discrimination campaigner and public interest litigant”, says he can’t comment on the complaints or his motives for “prosecuting” Gaynor because the matters are still before the courts.

But he says he has not personally pocketed any money from any of the claims he has lodged against high-profile or not so high-profile targets.

“I am not motivated by money,” he says. “The work I do is to remind people of their responsibilities.”

NSW Anti-Discrimination Board president Stepan Kerkyasharian says about a quarter of complaints are thrown out before respondents are even notified about them, on the grounds that they are frivolous, vexatious or do not fit within its legislation.

He says only about a quarter are transferred to the NCAT for determination after both parties have had a chance to put their views forward.

“Unless there is actual vilification people have nothing to fear,” Kerkyasharian says.

“Vilification laws are about vilification, they are not about the expression of opinion … If someone says, ‘I do not agree with same sex marriage or gay equality for the following reasons’, that’s not vilification or discrimination. The vilification laws allow for academic debate.”

Toowoomba GP and same-sex marriage opponent David van Gend has been forced to attend Queensland’s Anti-Discrimination Commission to respond to a complaint about an article he wrote for The Courier-Mail arguing against any change to marriage laws.

The complaint was ultimately withdrawn, but not before van Gend had been forced to give up time to appear before the commission and spent a few thousand dollars on legal fees.

“It costs you time, legal expense and anxiety, and although in my case there was very little of any … other people would not enjoy the experience,” he says.

Like Shelton and others, he believes vilification laws around the country are having a chilling impact on free speech.

“The fact that people out there have seen the Catholic bishops being taken to the thought police for issuing a very gentle and gracious exposition of their ancient beliefs to their own flock … means that people who don’t want grief will tend to stay silent now rather than risk trouble,” he says.

He believes reform is necessary to address the “intolerable” impact the anti-vilification provisions are having on free speech.

“We must not allow laws to be misused to suppress free argument on matters of public importance. These laws do that so they must change,” he says.

The Australian Christian Lobby and free market think tank the Institute of Public Affairs have backed those calls to overhaul the law in the lead-up to the national plebiscite.

Shelton wants the Attorney-General’s Department to look urgently at options for allowing church groups and others to voice their opinions without the fear of legal action.

“I think we need an urgent commonwealth override of anti-discrimination legislation,” he says.

“This debate is going to run most likely for the next 12 months and it needs to run … (But) if every time we put forward the most inane arguments, as Bishop Porteous did … (we are) hit with an anti-discrimination complaint, how is that going to help our side of the debate put its views forward? We have to be free to speak, otherwise it’s not a fair fight.”

The IPA’s Simon Breheny believes section 17 of Tasmania’s Anti-Discrimination Act sets an “unreasonably low threshold” for unlawful conduct and should be amended. He says the legitimacy” of the plebiscite result will rely on the freedom of Australian citizens to voice their opinions.

“It is too easy to ‘offend’, ‘humiliate’, ‘insult’ or ‘ridicule’ a person in the course of robust debate,” he says.

“These words should be removed to ensure that a free discussion can take place.”

Wilson, who is in favour of same-sex marriage, similarly says it’s in the interest of those agitating for change to ensure a robust debate can occur.

Otherwise, he says, it will create “an opportunity for the no case to look like martyrs”.

“Equally, it’s just not good for a full public discussion so that people can be exposed to the arguments and see why the arguments against change are weak,” he says.

But it is hard for that to occur while the big stick of the law looms large.