Same Olympic Games, but Brisbane faces new rules

The wheels are already turning for Brisbane’s 2032 Games hopes.

The feasibility study into a proposed Brisbane 2032 Olympic bid is still two months from completion, and while nothing can yet be revealed about its findings and recommendations, it speaks volumes that the work is proceeding without interruption.

Scott Smith of the Council of Mayors, the political advocacy organisation set up to represent Brisbane and the other nine councils in southeast Queensland, has made it clear that only while the numbers stack up will work push ahead on the feasibility study.

“This has been a well-thought-out, detailed piece of work that we’re going to do and will continue to do while we are comfortable that it’s something we should continue to invest in,” Smith says. “We are not rushing into this. We have not let it go to our heads and just jumped on a fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants kind of idea.”

The mere fact, then, that the work is continuing allows for some positivity. There is a growing perception that at this precise juncture in history the International Olympic Committee may be ready for an economical Games, as oxymoronic as that might sound.

The International Olympic Committee, humiliated by the corruption and scandals associated with past Games bids, has radically amended both its bidding process and its vision of what future Olympics might look like to make it possible for more cities and regions to stage Games that will come in on budget. Words like “reusable”, “temporary”, “demountables” are to be found liberally throughout the pages of The IOC — The New Norm, which is not a reworked version of the old national fitness advertising campaign but a document committing the body to making the process of winning and then running the Games more cost-efficient, transparent and flexible.

“We firmly believe that there is an opportunity here that is ripe for the picking,” says Smith. No doubt he is encouraged that the retrospective application of The New Norm allowed Tokyo to slash $3.1 billion from its budget for the 2020 Games. And even when budgetary constraints are exercised from the get-go at future Games, the IOC document suggests $1.35bn worth of cuts can be found. It was very much a story of the times when the IOC suggested that in future the Games village newspaper be delivered entirely online.

Yet even these savings, in the grand scheme of things, are relatively small. The main advantage in shooting for the Games is that it drives a stake into the ground and demands the delivery of infrastructure that otherwise might have been deferred for years, decades even. The consensus is that there is no way the Gold Coast would have had a light rail system in place by this year had it not staged the Commonwealth Games in April.

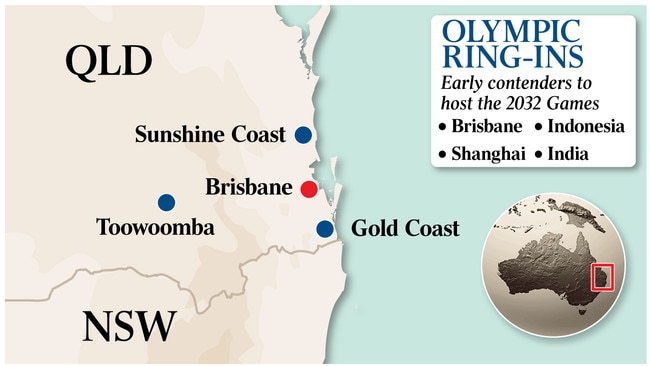

So it is with the planned $70bn scheme to dramatically improve the “connectivity” of the southeast corner by installing a fast-rail network linking Brisbane with the Gold and Sunshine coasts and Toowoomba. These are not “bullet train” lines of the type envisaged from Melbourne to Sydney but rather rail corridors where average speeds of 150km/h are reached, more than fast enough in an urban or semi-urban setting, especially compared to the current 60km/h.

It would bring the commute from Maroochydore to Brisbane down to about 45 minutes, which would make such a trip eminently doable on a daily basis. Moreover, it brings the Sunshine Coast, indeed the entire southeast Queensland region, on line as an accommodation centre for an Olympic Games.

Like it or not, the $70bn is going to be spent by 2041. What the feasibility study is considering are the advantages of bringing forward that investment to 2031, a year out from the Games. It’s not new money or different money but, thanks to the stimulus of an Olympics, Brisbane and its surrounding councils would reap the financial benefits of it 10 years earlier.

And it’s not just rail. The Cross River Rail and Brisbane Metro plans have their own rationale, their own proposed budgets. And while the feasibility study has not identified the need for any sort of significant extension to Brisbane’s tunnel system, there are still roads to be provided, along with general infrastructure and technology. Who knows where technology will have swept us by 2032?

OK, time to cut to the chase. There is only one way a Brisbane Olympics bid will happen, according to former Queensland premier Peter Beattie, who headed the Gold Coast organising committee for the Commonwealth Games before becoming chairman of the Australian Rugby League Commission.

“It could be the catalyst for a really dynamic southeast corner but unless they get it underwritten by the federal government, it’s never going to happen,” Beattie says. “To be honest, the federal government has to do the heavy lifting. It’s more like 50 per cent commonwealth, 25 per cent state, 25 per cent local council. State governments and councils don’t have the money. The commonwealth has.

“The problem we’ve got is the state of politics in this country.

“Trying to find anyone with enough guts and enough vision to do anything is really difficult. It’s all about day-to-day politics. You need bipartisan agreement. You need the prime minister and the leader of the opposition to sign off on this.

“If you think about when it’s going to happen (2032), there will be several changes of government and many changes of prime minister.”

They can be listed on the fingers of a sawmiller’s hand, the number of nation-building projects the commonwealth has embraced over the past half-century — the Snowy Mountain Scheme, the Sydney Olympics, the … ummm. The fact is that there aren’t many of them at all and so far they’ve all been directed into the southeast corner of the country, where the major population centres have been.

But now the population is on the move. The southeast corner of Queensland is home to one in seven Australians and over time that ratio will shrink even further. Yet, as Beattie says, does Australia still have the capacity to look beyond the immediate 24/7 news cycle to the needs of a time 14 years down the track, when no one will recall whether it was Scott Morrison or Bill Shorten or someone else who had the vision to back a Brisbane bid? And do the Games even rate in the halls of power, especially in the light of the fact that 40 or so of the country’s finest Olympians have been forced to put out the begging bowl to protest against federal government funding cutbacks?

Assuming that a prime minister of the near future does commit, then what? The first thing is to adjust to the idea of competition. There is talk of a Games unifying South and North Korea. There is talk of the first African Games. India is considering raising its hand. And IOC president Thomas Bach has spoken fondly of bringing the Games back to his native Germany.

There are compelling reasons why the Olympics have not been held before in some of those places. Recall that the 2024 and the 2028 Games are going back to Paris and Los Angeles for the third time in their histories. Recall, too, that former IOC president Jacques Rogge made a personal call on Beattie when he was in office to request a Brisbane bid, while Bach noted that there were three Australian cities capable of hosting the Games, two of which had already done so. In short, the IOC loves coming here. It’s a safe, happy environment. They know Australians can deliver.

Most important of all, Australia’s John Coates is now the IOC’s co-ordination committee chairman, meaning he (almost) literally wrote the book on how to bid for the Games.

Still, Australia had two failed Olympic bids — the first of them in the late 1980s when, with Coates providing the strategy and Sallyanne Atkinson the charm, Brisbane placed a respectable third in the race for the 1992 Games — before Sydney finally broke through. That healthy chariness is now being put to good use as the Council of Mayors weighs up whether it is worthwhile entering the fray again. Yet Smith also says there are other factors at play in the assessment stage.

“It’s the aspiration of what we could do with the region and if we’re serious about stepping on to the world stage, then we have to look at these big-picture things.

“And despite what people might think, we’re not doing this as a folly, (we’re) thinking of massive public spending on the public purse. We’re very conscious of the cost of these things and the benefits.”

Brisbane has its own Commonwealth Games legacies of 1982, including the major complexes at Chandler, Nathan and QE II, and the Gold Coast Games in April injected new facilities into the southeast Queensland sporting infrastructure.

Yet Beattie believes it would be in Brisbane’s interest to expand its Olympic bid to incorporate western Sydney. He knows the idea will be unpopular with Queenslanders — and a hurriedly conducted vox pop confirmed his suspicions — but aside from spreading the costs, it would also bring into the mix millions of potential spectators and, significantly, the Sydney Olympic facilities, especially a refurbished ANZ Stadium.

“This comes down to size and economies of scale and for the opening ceremony, you need ANZ unless you are prepared to build a brand new $600 million to $700m stadium in the southeast corner of Queensland,” says Beattie.

As it happens, they are. What the precise budget would be is open to debate, but the Council of Mayors has already identified the need for a second rectangular stadium to support Suncorp, independent of an Olympics.

That would be Brisbane’s Olympic legacy, a 50,000 to 60,000-seat stadium. Whether the long-term viability of the stadium would be compromised by putting a synthetic athletics track inside it — which limits the ground’s use thereafter to oval sports like AFL and cricket — or whether Brisbane breaks new ground by having a rectangular main Olympic stadium are all issues still to be debated.

Inevitably, that debate strays quickly from “what type of stadium” to “where would it be built”. At this point, there are no wrong answers. Even the feasibility study hasn’t firmed up a site yet. The Roma Street railway yard is one solution, but what would be the purpose of building a rectangular stadium just a 10-minute stroll from the existing one at Lang Park?

Victoria Park golf course would offer a centrally located precinct where a number of Olympic sports, and the main stadium, could be brought together, although it would have to be done in a way that preserved open green space in the CBD. And let’s not forget the golfers of Vic Park, who must feel like their course is being squeezed in every possible way.

The Games undoubtedly hold out the prospect of Brisbane being left a legacy of a central sporting complex akin to Melbourne’s world-renowned grouping of the MCG, AAMI Park, the National Tennis Centre and Olympic Park. But that, it seems, would be an accidental bonus. There are no plans to replicate that arrangement.

Whatever happens, southeast Queensland is entering into this whole Olympic bidding process in a detached and clinical fashion. It may have been a masterstroke by the IOC to award the 2024 and 2028 Games simultaneously. Paris and LA were both outstanding candidates and it just made sense. The cynics, however, might suggest that the IOC was locking them in at a time when bidding cities were thin on the ground, thanks to the exorbitant excesses of the recent past.

The excitement of the Games will come later. For the moment, Brisbane is taking a very sensible “what’s in it for us?” approach.

Wayne Smith has covered the last eight summer Olympic Games.His column in The Australian in February 2015 recommending a Brisbane Olympic bid led to the feasibility study being set up.