No escape for El Chapo

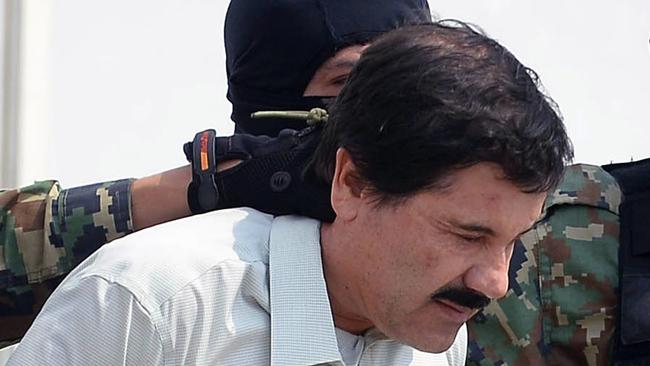

Joaquin Guzman’s life of defying the authorities and ruling over a deadly drug cartel is surely at an end.

“Behind the mountains of Sinaloa, a bonfire roared in what would become a shallow grave.”

So began the closing argument against Joaquin Archivaldo Guzman Loera — better known as “El Chapo” — who was found guilty yesterday of running the world’s largest drug-trafficking empire.

New York prosecutor Andrea Goldbarg wanted to show the jury that the Mexican drug lord was born with a heart of darkness, capable of committing acts of unspeakable cruelty.

So she recounted how, in 2007, Guzman personally tortured two members of a rival cartel with stakes for three hours as he ordered his men to dig a hole and light a bonfire.

The men were “beaten almost to death but still breathing” when Guzman shot them both in the head and ordered his men to throw them into the fire, she said.

“I don’t want any bones to remain,” Guzman told them as he left.

It was hard to reconcile such gruesome acts with the small, well-dressed man in a suit who smiled and waved at his wife after a New York jury declared him guilty of 10 federal crimes, ensuring that Guzman, 61, will spend the rest of his life in prison.

But the world’s most notorious drug lord built his empire in part because his enemies, from rival cartels to the police, gravely underestimated this short, chubby man from a dirt-poor Mexican family.

No one underestimates Guzman any more. The guilty verdict after a 12-week trial confirms what the rest of the world has long suspected: Guzman was the mastermind behind the most deadly and prolific drug cartel, having masterminded the trafficking of an astonishing $US14 billion ($19.7bn) worth of drugs. He was a businessman, a ruthless killer and a showman all in one. Netflix has already made a series about his life and Hollywood is circling.

In between pioneering new ways to traffic drugs and assassinate enemies, he cavorted with Hollywood stars, bedded beautiful women and showed off his diamond-encrusted handgun and gold-plated AK-47.

Actor Sean Penn took a small plane over the jungle for a tequila-fuelled interview with Guzman in his mountain hideaway in Sinaloa. Penn wrote in Rolling Stone magazine: “Since he joined the drug trade as a teenager, Chapo swiftly rose through the ranks, building an almost mythic reputation: first as a cold pragmatist known to deliver a single shot to the head for any mistakes made in a shipment, and later, as he began to establish the Sinaloa cartel, as a Robin Hood-like figure who provided much-needed services in the Sinaloa mountains, funding everything from food and roads to medical relief.

“By the time of his second escape from federal prison, he had become a figure entrenched in Mexican folklore.”

Guzman’s prosecutors were unimpressed by this rose-coloured view of the drug lord by an awe-struck Penn. Judge Brian Cogan was asked to exclude any mention of the interview at the trial.

Instead, prosecutors painted Guzman as a dark and deadly soul who would come to mistrust everyone around him, including his wife, former beauty queen Emma Aispuro, and his many mistresses.

Guzman, they said, employed sicarios, or hitmen, who carried out hundreds of acts of violence, including murders, assaults, kidnappings, assassinations and acts of torture at his direction.

Given Guzman’s colourful past, it wasn’t surprising that the trial was a showstopper.

A master escape artist, Guzman was accompanied by a SWAT team and a helicopter whenever he was transported to the Brooklyn courthouse.

His glamorous 29-year-old wife attended each day, surrounded by reporters and often wearing outfits co-ordinated with her husband’s, in solidarity. She watched on stoically as one of Guzman’s mistresses tearfully recounted to the court the night in 2014 when Mexican marines tried to break in to a house where they were hiding. A naked Guzman jumped into a tunnel under a bath and escaped through the sewers.

Actor Alejandro Edda, who plays Guzman in the television series Narcos: Mexico , came to watch the proceedings, prompting a smile and a nod from Guzman.

“It’s a rare opportunity,” Edda said. “What else could be better than to see the man in real life, learn his mannerisms?”

The court heard how Guzman began at the age of 15 as a small-time marijuana seller.

“The only way to have money to buy food, to survive, is to grow poppy, marijuana, and at that age, I began to grow it, to cultivate it and to sell it,” he told Penn in 2015.

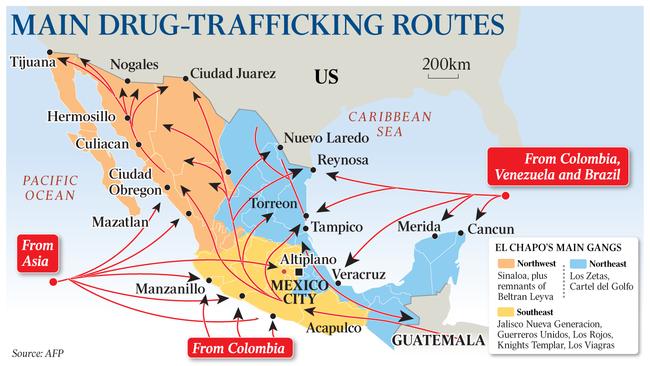

He became famous for digging elaborate tunnels under the Mexican border, earning the nickname “El Rapido”. He later used planes, trains, cars, fishing boats, container vessels and even submarines to smuggle drugs into the US.

He also expanded his trafficking to include cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine and marijuana. But it was a business that was infected by jealously, betrayal and backstabbing.

The court heard that, in 1992, Guzman moved to consolidate his rising power by settling a score with a rival gang. He ordered a band of assassins to enter a crowded disco in Puerto Vallarta in Mexico and open fire on the rival gang. Six people died.

Notorious in the underworld, Guzman became a public figure after two daring prison escapes.

In 1993 he was captured in Guatemala and sent to Mexico’s high-security Puente Grande prison. Eight years later he escaped, reportedly in a laundry cart.

In early 2014 — after he had built his drug empire — Mexican navy commandos tracked him to a condominium on the coast. They burst into his room and captured him.

This time he was taken to the country’s highest-security prison, outside Mexico City, called the Altiplano. Guzman instructed his men to dig a tunnel to his cell. A year later he jumped into the tunnel and rode a motorbike to freedom.

The trial heard that, at the height of his reign, Guzman had carved out an extraordinary world in his mountain hideouts of Sinaloa.

He had a private army, a rotating group of chefs, and a zoo with lions and tigers and a small train running through it. To relax he would shoot bazookas, fly in one of his four jets or sail his yacht to one of his many beach homes. When business had to be done, he had a “murder room”, which was soundproofed and had a drain in the floor to clean up afterwards.

A combination of ego and paranoia brought down El Chapo.

The court heard he became so paranoid about being caught that he wire-tapped friends, colleagues and family, including his wife and mistresses.

His biggest blow came when the cartel’s IT expert, Christian Rodriguez, 32, who had set up the spying network for his boss, turned into an informer.

Rodriguez allowed the FBI to use the system. When Guzman found out he had been betrayed, he ordered Rodriguez’s murder but they could not find him. As Goldbarg told the court: “Luckily, no one knew his last name and (they) never found him.”

Investigators accumulated what they called “a mountain of evidence”, including more than one million intercepted messages between cartel members.

The FBI learned that Guzman had been in touch with actors and producers to make a movie about his life, and they tracked the communications to a house in Sinaloa.

In January 2016, Mexican special force soldiers stormed the house. Guzman escaped by flicking a switch, which activated a trapdoor behind a mirror, and ran through the sewers. But he was once again captured and this time extradited to New York in early 2017.

Although prosecutors had powerful electronic evidence against Guzman, they needed to persuade his former cartel partners to risk their lives by taking the stand against him. Eventually 14 of them did, giving sometimes stunning testimony.

Cartel member Alexander Cifuentes claimed Guzman paid then Mexican president Enrique Pena Nieto $US100 million to stop hunting for him after he escaped prison.

Nieto’s spokesman denies the allegation, describing it as “false, defamatory and absurd”.

Guzman’s lawyers argued he was not the head of the cartel and that the prosecution witnesses were themselves criminals and “gutter human beings”.

“They’d run over their mother to convict that man,” defence lawyer Jeffrey Lichtman told jurors. “Those witnesses told lies every day of their lives — their miserable, selfish lives.”

Goldbarg countered: “Ladies and gentlemen, these witnesses are criminals, the government is not asking you to like them”, adding that their stories were consistent with other evidence.

Another prosecutor, Amanda Liskamm, said that if the 14 people testifying against Guzman were somehow making up their stories, “you have to believe that the defendant is the most unlucky man in the world”.

No more escapes are likely. Guzman has been in solitary confinement since early 2017 in the harsh Metropolitan Correctional Centre in lower Manhattan, spending 23 hours a day in a small, windowless cell.

“His meals are passed through a slot in the door. He eats alone, the light is always on. He never goes outside (and has) no way to distinguish night from day,” his lawyers wrote.

Now a maximum-security prison awaits Guzman, who faces a mandatory life sentence in June.

“Guzman Loera’s bloody reign atop the Sinaloa cartel has come to an end, and the myth that he could not be brought to justice has been laid to rest,” US Attorney Richard Donoghue said yesterday.

“There are those who say the war on drugs is not worth fighting. Those people are wrong.”

Mike Vigil, a former operations chief at the US Drug Enforcement Administration, said: “The American public should have gotten a tremendous education if they paid attention to the Chapo Guzman trial, because it provides an in-depth look at the way these cartels operate and the violence and corruption they generate, and the fact that they generate billions of dollars.’’

When you look at what Guzman created, Vigil said, it was a business empire, except that it existed on the wrong side of the law.

“He created a transnational organisation that rivals any major corporation.”

A year before he was captured for the last time, Guzman told Penn that he hoped he would not die a violent death.

“I know one day I will die. I hope it’s of natural causes,” he said.

The New York jury has all but guaranteed that his wish will come true.

Cameron Stewart is also US Contributor for Sky News Australia