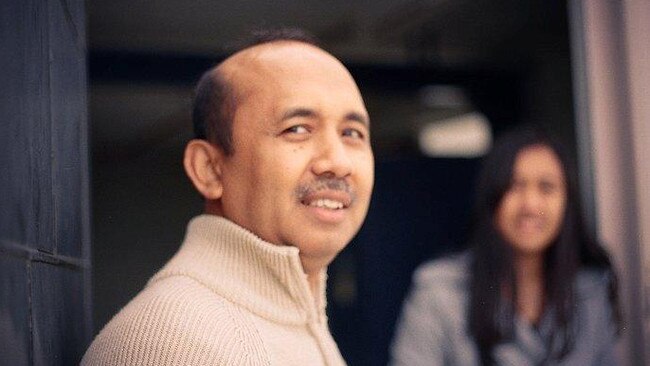

MH370 pilot’s emotional final farewell?

Investigators may be trying to clear MH370’s captain of suspicion, but the facts point straight to him.

The Malaysian government had a lot riding on its much-anticipated safety investigation report into the loss of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 — and so did the Australian Transport Safety Bureau.

It has been 4½ years since the Boeing 777 disappeared on a scheduled flight from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing, and the families of the 239 people on board had hoped the Malaysian report, released late last month, would provide some answers to help them reach closure.

The international aviation community also was looking for at least a rational assessment of what most likely happened on the balance of probabilities.

The Australian government’s reputation also was on the line: the ATSB was one of the accredited representatives on the investigation panel under what is known as the International Civil Aviation Organisation’s Annex 13 air accident protocol.

Under that protocol the ATSB had the opportunity to have its own separate opinions and assessments included in the Malaysian safety investigation report, but it accepted the report without comment.

I have been on the board that investigated an aircraft accident when I was in the Royal Air Force and I am well aware of the difficulties and the painstaking process leading up to the final findings. Like all investigations, the credibility of the findings in the Malaysian MH370 report depends on the exhaustive analysis of information that is gathered.

Furthermore, unless the investigation has been pursued without bias, prejudice or a preconceived conclusion, it is flawed and open to criticism.

The Malaysian investigation, to my mind, has failed on all of these criteria and has not provided justice to the victims and families. The one factor that has not been adequately addressed in the main report of 450 pages and another 1000 pages of appendices is pilot involvement. I hold the opinion that this was not an accident but the deliberate destruction of the aircraft, resulting in the deaths of 238 innocent victims.

The Malaysian investigation concluded it could not determine what happened to MH370.

But in the press conference releasing the report, Malaysian chief investigator Kok Soo Chon placed a lot of emphasis on possible “third party” involvement, suggesting a hijack by one or more passengers, and appeared to clear the pilots from suspicion.

Of the captain, Zaharie Ahmad Shah, Kok said: “He was a very competent pilot, almost flawless in the records, able to handle work stress very well. We are not of the opinion it could be an event committed by the pilot.”

Most observers in the professional aviation community believe pilot hijack by the captain is the only realistic scenario that fits with the known facts, and the Malaysian report, and by implication the ATSB, shied away from it.

MH370 departed Kuala Lumpur airport at 42 minutes past midnight local time on March 8, 2014, with 227 passengers and 12 crew. Zaharie was pilot in command, and the first officer was Fariq Abdul Hamid.

Up to the cruise altitude of 35,000 feet the flight was uneventful. However, shortly afterwards there was a series of abnormal events. About 40 minutes into the flight, Kuala Lumpur air traffic control gave a radio frequency change to contact Ho Chi Minh City air traffic control. Zaharie famously responded with “Goodnight, Malaysian Three Seven Zero” in a calm voice. However, he failed to read back the frequency he had been given, which is a required response.

Within less than two minutes from Zaharie’s radio call the aircraft’s secondary radar transponder was turned off, meaning it disappeared from the screens of air traffic controllers, and the aircraft began an aggressive left turn through 180 degrees.

As far as air traffic control was concerned, the aircraft was now invisible, and the knowledge of this turn and the aircraft’s subsequent flight path was revealed only later, after reviewing military primary radar. This is where it becomes more interesting.

The turn was timed to have taken two minutes and eight seconds, and subsequent simulator trials revealed it could not be replicated by using the autopilot — the aircraft had to be manually flown. Furthermore, to achieve this turn rate there would have been an audio “bank angle” warning and additionally the stick shaker (stall warning) would have been activated. To fly the aircraft in this manner, on a dark night with no moon, with few if any visual clues and without losing control, would require a degree of skill and familiarity with handling the B777.

The report’s statement “the possibility of intervention by a third party cannot be excluded either” raises the question as to how a third party could have gained access to the cockpit, disabled the aircraft’s electronic equipment, “neutralised” the two pilots, then seated themselves before flying the aircraft through a demanding manoeuvre in the space of two minutes. It beggars belief. Besides, access could be gained only through a locked cockpit door that is also monitored by a flight deck entry video system from the cockpit.

After the sharp turn, the aircraft took up a southwesterly track to a point 10 nautical miles south of Penang Island, where it then flew a lazy turn to the right before joining one of the thousands of official airway routes, in this case airway N571.

Zaharie was born and went to school in Penang, so the routing of the aircraft could be regarded as significant. The 10NM displacement to the south of the island would have provided him with a good view from the left seat of the aircraft. This could be interpreted as a last, emotional farewell.

After the Penang overfly, the aircraft continued to progress up the airway to the north of Sumatra before turning south on to a southerly heading into the Indian Ocean.

The report found the aircraft was airworthy and any technical issue that could have affected the flight was improbable. Similarly, after significant testing of the cargo contents — an odd mix including mangosteens and lithium ion batteries, which some theories suggested could have caused a fire if the fruit leaked on to the batteries — no issues were raised.

The aircraft did not fly by itself, which means in all likelihood one of the two pilots was responsible for what in effect was an aircraft hijacking — and it is highly unlikely to have been the first officer.

It would be very easy for Zaharie, under some pretext, to ask the first officer to retrieve something from the cabin. Once he was outside Zaharie could have locked the cockpit door and thereby been free to take whatever action he wished with total impunity. My belief is Zaharie deliberately locked the first officer out of the cockpit, then disabled the aircraft transponder and automatic flight data and communications system. He then manually flew the tight 180 degree turn towards Penang, after which he depressurised the aircraft — which resulted in the death by hypoxia, or lack of oxygen at high altitude, of the passengers and remaining crew.

To my mind the circumstantial evidence points to the captain hijacking his own aircraft. One indicator is the timing. The radio frequency and air traffic control change 40 minutes into the flight was an ideal time to go missing by turning off the transponder and ceasing radio transmissions. It proved very successful in creating confusion among controllers in Kuala Lumpur and Ho Chi Minh City, and thereby substantially delaying the subsequent search.

The report also conflicts with its own content. For example, on page 6 it states: “On the day of the disappearance of MH370, the military radar system recognised the ‘blip’ that appeared west after the left turn … was that of MH370.

“Therefore, the military did not pursue to intercept the aircraft since it was ‘friendly’ and did not pose any threat to national airspace security, integrity and sovereignty.”

Really? In my fighter pilot days there would have been a scramble to intercept the aircraft to find out what was happening.

However, it gets even better on page 337: “In interviews … controllers informed that they were unaware of the strayed/unidentified aircraft (primary radar target) transiting.”

The contradiction between these two statements creates an element of doubt about other sections of the report.

In the absence of any other likely cause for MH370’s disappearance, the investigation should have paid far more attention to Zaharie’s possible involvement.

It is known that Zaharie had co-ordinates in his home simulator that were similar to MH370’s final route into the southern Indian Ocean. Indeed, one of the co-ordinates was only a little farther south than the point where the aircraft ran out of fuel. However, the Royal Malaysian Police forensic report “concluded that there were no unusual activities other than game-related flight simulations”.

This report is in stark contrast to an independent investigation led by US engineer and entrepreneur Victor Iannello that found several co-ordinates in Zaharie’s computer matched MH370’s final flight into the southern Indian Ocean. I find it difficult to take the Royal Malaysian Police report as a serious contribution to the investigation.

In regard to fuel, the report says “there was also no evidence that more than the reasonable amount required was carried”. I disagree. The weather at Beijing was well within landing limits yet, despite planning on an alternative airport 45 minutes away, Zaharie also carried additional fuel for an extra one hour and 45 minutes from his destination.

Carrying extra fuel unnecessarily incurs a considerable cost and I would not expect that from an experienced captain. In effect, Zaharie carried 3000kg of additional fuel above what was required, and this equates to an additional 30 minutes of flight and an extra range of 250NM.

Zaharie was passionate about politics and democracy. He was a fervent supporter of Anwar Ibrahim, who was then leader of the opposition party in Malaysia and distantly related by marriage. In 2012, Anwar was acquitted of sodomy charges. However, the decision was appealed and Anwar was declared guilty and sentenced to prison on the day Zaharie reported for his flight.

From what I understand, Zaharie was upset about Anwar’s fate. There is no mention in the investigation regarding Zaharie’s involvement in politics — I feel it is relevant and should have been addressed.

From a pilot’s point of view, MH370’s deviation from its planned route shows that the person flying the aircraft had meticulously planned, and executed, an aircraft hijacking.

It’s also a reasonable assumption that he would stay conscious until the end. Why then does the Malaysian government, and indeed our ATSB, insist that this was a “ghost flight” with dead pilots at the end?

There is little or no evidence to support this supposition. On the other hand, there is ample evidence that the aircraft was ditched in a controlled manner with the flaps in the landing position. This totally dispels the “ghost flight” theory.

Several aircraft pieces were washed up on Indian Ocean islands and mainland Africa. Among these recovered items were a flaperon and an outboard flap. Both items were from the right wing. The flaperon was washed up on the French island of Reunion, and the subsequent damage study by French experts indicated it was in the down position on impact. This information was passed on to the Malaysian government and the ATSB more than two years ago.

Further examination of the flaperon and outboard flap by Larry Vance — a highly experienced Canadian air accident investigator — clearly shows witness marks and damage that could have occurred only if the flaps were down when the aircraft made contact with the sea. Vance’s book MH370: Mystery Solved provides a detailed explanation of why the aircraft must have been ditched as opposed to having crashed down uncontrolled.

The search area has been based on the assumption that the aircraft crashed in a steep dive immediately after it ran out of fuel. The possibility that the aircraft was ditched has been totally ignored by the ATSB and the Malaysian investigators. This makes a significant difference to the search area because if the aircraft was ditched it would have flown for the best part of another 100NM.

Simon Hardy, a former British Airways Boeing 777 captain, provided detailed information on the aircraft track and likely area to search if a ditching had been made. This information was passed on to the ATSB not long after the search it was leading began. Unfortunately it has not been put into effect and a fruitless search, wasting time and money, has been driven by the assumption of a “ghost flight” followed by a near vertical dive.

I have little doubt that this was a well planned and executed deviation from the initial flight path between Kuala Lumpur and Beijing. At the time of MH370’s fuel exhaustion the sun was 7 degrees above the horizon. Was this fortuitous or well planned? Note the extra fuel carried.

A ditching would not be a severe challenge to an experienced pilot, and it would help sink the aircraft in only a few parts rather than creating a big debris field.

The wind was from the southwest at 15 to 20 knots with a moderate swell. Landing into wind, on the back of the swell with the sun behind, would result in the engines being ripped off and the right wing being pulled back and possibly detached.

The witness marks and damage to the flap and flaperon match this scenario. All the material available to me, Hardy and Vance was available to the ATSB and the Malaysian investigation team. They either failed to interpret it correctly or, worse still, at least subconsciously avoided it because it contradicted their original “ghost flight” theory.

The ATSB is complicit in the deeply flawed Malaysian government MH370 safety investigation, by granting Australian government endorsement to the final report without comment.

Transport Minister Michael McCormack should demand the ATSB publicly account for why it did so — the families of the six Australians on board MH370 deserve nothing less.

-

Mike Keane has spent 45 years in aviation. He served for six years as a navigator in the RNZAF and 14 years as a fighter pilot in the RAF. He then spent 25 years as an airline pilot, of which half was in management, including as chief pilot of Britain’s largest airline, easyJet.