Liberals’ war chest divides the powerbrokers

The party’s quest for a new model of funding risks stirring divisions.

For a big political donor, thanks often come in small ways — the first name “hello” as a Prime Minister handshakes through a crowd; the seating plan at an event; most personal of all, the prestige of the hand-signed Christmas card on the mantelpiece that shouts “connected”.

But in these days of virtual reality, Malcolm Turnbull has dispensed with the signed card-in-the-post to donors and other important party supporters, instead emailing a personalised mass e-card bearing his season’s greetings.

It has been met with disappointment and clenched-teeth in many quarters; after all, you can’t showcase an email on a bookshelf, admitting: “Oh that came from Malcolm and Lucy!”

Splitting hairs over whether the Prime Minister sends cards has an air of trivia; but for a political party in such financial trouble that it had to slash by two thirds its nightly phone-polling research in the 2016 federal election (in the order of thousands of calls per night never made, according to the party post-mortem), every calculated move to massage the donor base counts.

One of the party’s most senior figures — a fundraiser for many years — was so concerned about the Prime Minister’s resistance to the card-in-the-mail that he pressed Liberal federal treasurer Andrew Burnes late last year. He suggested Burnes provide the cards in a stack for signing during spare moments on a plane. The suggestion came to nought. Burnes did not respond last week to questions.

One major donor said this week that no one he knew had received a real card in the post. “There’s been a virtual drought,” he declared. A spokesman for the Prime Minister confirmed the cards for Christmas were digital.

Turnbull’s predecessor Tony Abbott signed and sent out almost 3000 cards at Christmas, (signing many on a plane). John Howard, the master of etiquette, always signalled gratitude; he knew supporters appreciated tearing open the envelope. As a strategy to make donors feel warm, nothing says “insider” like a signed memento.

Turnbull himself was of course the biggest donor to his own re-election in 2016, giving a declared $1.75 million. Turnbull’s donation came in the shape of a guarantee to the federal party enabling a last-minute advertising blitz in the late stage of the campaign — with the actual cash materialising as soon as the bills came in.

This year, party officials hope to trot the Prime Minister out as a regular attraction in the hope his presence will loosen wallets for party events. Turnbull, they say, has never warmed much to the machinery of politics and in particular to headlining fundraisers. But in the face of a serious financial struggle, he is now scheduled for a number of functions this year.

Numerous older-wealth families and companies have cut back or closed shop on donations, leaving the party urgently, yet again, exploring funding models for high volume, low value.

The big four banks as donors — some of whom provided the backbone in tough times — have been in retreat for several years although there was an uptick in the 2016-17 disclosures.

NAB revealed in 2016 that it had already stopped making political donations. This was a significant blow. In the 2014-15 year, NAB had donated $239,686 to the Coalition (and $35,600 to Labor). A year later there was nothing from NAB, $27,500 each from Westpac and CBA and $100,000 from ANZ. Not much for a party that had literally struggled to keep the lights on.

By 2016-17, Australian Electoral Commission records show NAB again gave nothing; Westpac gave two donations of $27,500 almost a year apart and then a third donation of $12,650; CBA gave two donations, $27,500 and $12,650; and ANZ gave $150,000.

A year ago Turnbull justified his own massive contribution when he revealed then federal director Tony Nutt had been asked to work for no salary for the first few months after his appointment in 2015. Such was the parlous state of affairs. “At the end of 2015, when Tony Nutt became the director of the Liberal Party, the party had so little money he had to work for several months without any pay, so the party was very short of money,” Turnbull told Nine’s Laurie Oakes.

The party’s biggest donor, the Liberal-aligned Cormack Foundation, is now in limbo, caught in a pending court battle that has shocked everyone and opened rifts behind the scenes among top Liberal officeholders.

Cormack as a company was founded on the profits of the $15m sale of the Liberal-aligned 3XY radio station in 1986. Since the late 1980s Cormack directors have given the party $60m — entirely from dividends, while preserving untouched capital now worth almost $70m.

In 2016, Cormack donated $1m to the federal Liberals for the election campaign, although Turnbull had met with members of the board and asked for $3m. Cormack directors apparently agreed to consider the request, but, unwilling to spend anything outside accrued dividends, sent the party only $1m.

At the same time, a wrestling match over the $70m was already under way between the Cormack board and Michael Kroger, the Victorian Liberal party president; Kroger took a stand that both the capital and the dividends of Cormack were wholly the property of the Victorian party. The Victorians were still riding out the impact of a massive $1.5m fraud by a former Liberal state director, and if there was Cormack money likely to be available (for the feds) then Kroger had been arguing it should be given to the Victorian branch.

The objects of the Cormack Foundation’s constitution directed it to promote libertarian causes and individual enterprise: it could grant donations “for any public purpose or for any object of the company”. Because two of the first directors, Hugh Morgan and John Calvert-Jones, had signed side-letters to ensure they used their best endeavours for the benefit of the Liberal Party, Kroger argued this meant the funds were the property of the party.

When Cormack made two small but controversial donations — $25,000 each to the (now non-existent) Family First party, and the Liberal Democrats, Kroger claimed the grants breached the Cormack constitution. Ironically, Kroger himself was a director of the Institute of Public Affairs for almost seven years when the IPA received an average of $300,000 a year.

By the middle of last year, with the Cormack board dug in, Kroger and the Victorians triggered legal action set to commence this month on March 19. Both sides claim they have principle on their side.

Amid the drama, however, there were smoke signals that the federal Liberal Party was not aligned with Kroger’s decision. This, after all, was also the federal party’s own long-time biggest donor (outside Turnbull’s one-off gift of $1.75m).

The battle between Kroger and the Cormack board showcased a particularly bizarre moment on Wednesday, June 21, last year — a sunny winter day of mostly 12C — when one of the more aggressive letters ever sent by the Liberal Party whisked from the Victorian branch office at 104 Exhibition Street to the office of then Cormack chairman Morgan at 333 Collins Street, Melbourne. It was a 10-minute walk but just a click by email.

The letter demanded that all directors — including former Western Mining boss Morgan, stockbroking legend and former ANZ chair Charles Goode, former stockbroker Calvert-Jones (brother-in-law of Rupert Murdoch) and five other leading businessmen must stand down and hand over their board seats to a group of party stalwarts.

These proposed directors were: then party president Richard Alston, former party president Alan Stockdale, former federal MPs David Kemp, Michael Ronaldson and Fergus Stewart McArthur; and Robert Doyle, a former Victorian Liberal leader and long-time lord mayor of Melbourne who stood down in February this year over allegations of sexual harassment.

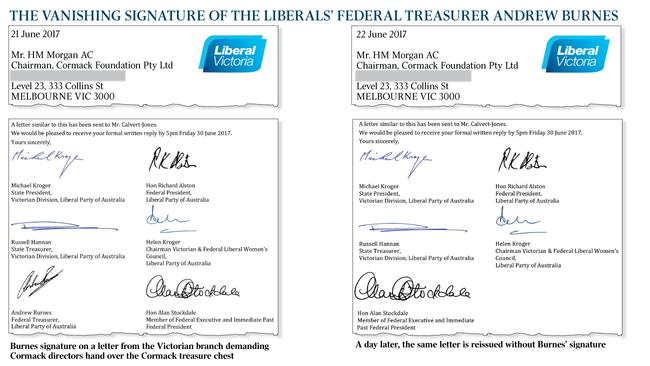

The June 21 letter was signed by Kroger, Alston (whose term as party president expired three days later), Women’s Council chairwoman Helen Kroger (ex-wife of Michael Kroger), Stockdale, honorary state treasurer Russell Hannan, and the federal Liberal Party’s chief fundraiser, travel entrepreneur Andrew Burnes. With Alston set to retire 72 hours later as president, it was Burnes’s signature on the letter that gave it the federal party’s imprimatur. A copy of the letter was sent simultaneously to Calvert-Jones.

The following day, the same letter was reissued by the Victorian branch with all the same signatures ranging from Kroger to Alston — but with the signature of Burnes removed. The weird sequence of two identical letters of a threatening and legalistic nature — sent a day apart and one with a signature removed — gave at least the appearance that some sort of skulduggery — or major bungle — was afoot.

Behind the scenes, the rumour mill — which made it into this newspaper’s Margin Call column at the time — alleged that Burnes had been unaware his signature had been used and that when he found out, he had demanded it be taken off the letter. And moreover, that he had been sufficiently angry that he contacted Cormack directors to apologise.

From those close to Kroger, a different claim ensued: that Burnes had been more than happy to slug it out with the Victorians against Cormack; that he had agreed to the use of his signature, but by that night he came under pressure from “others” at the federal level not to get involved; his signature was promptly removed to save him further embarrassment.

It was far from a storm in a teacup. Burnes’s signature was on file in the Victorian branch from the days when he was honorary state treasurer of the branch from 2009 to 2011. Suddenly it was on an exceedingly threatening document directed at the party’s biggest donor. Had Burnes agreed to join the attack on Cormack and given permission for his electronic signature to be extracted from a database for use? Had his PA sent it to a Liberal Party PA? Burnes declined to answer questions from this newspaper.

The June 21 and June 22 letters, obtained by The Australian, reveal how swiftly the first letter was replaced with Burnes’s signature removed.

Some senior Liberals point to the fact that the federal party has made no move to publicly back Kroger’s campaign against Cormack, nor to join the legal case as an interested party. On the other hand, during a federal executive meeting on June 23 last year, Turnbull was said to have mounted no defence of Cormack directors after an aggressive denunciation by Kroger. Some in the meeting claim Kroger called into question the integrity of Goode and Morgan.

Three weeks after the letters from the Victorian branch demanding Cormack directors resign, both Morgan and Calvert-Jones quit the board apparently in protest over unresolved Liberal Party governance issues.

Control of the $70m fund now rests with the outcome of the court action as Liberal divisions around the country — to say nothing of the federal office — hold their breath wondering what it will mean if Kroger and the Victorians come out on top with a vast war chest in their hands. Will this be Liberal Party money or the property of the Victorians, and who will get a slice of the pie?

The parlous state of federal party finances was identified as a critical factor in the blistering report on the 2016 election delivered last year by former trade minister Andrew Robb. The post mortem report was kept secret at the time, but revelations in The Weekend Australian showed that the party was hamstrung by lack of funds for research, leaving the campaign sometimes flying blind as it attempted to run a political strategy without polling.

With the federal secretariat costing an estimated $3m a year to operate, including the research budget, a shift in control over the Cormack funds could easily open new party wars.

New federal party president Nick Greiner could find himself facing off against his predecessor Alston — who is potentially the new chairman of Cormack and in charge of who gets what out of the cashbox.

Greiner, who late last year ordered the federal Liberal polling to be restarted as a matter of urgency, is equally likely to have a strong view of priorities in any carve-up.