Labor polling may not be enough to make Shorten prime minister

Neither side can rest easy after Super Saturday.

Demographic profiling of recent key by-elections in New England, Bennelong, Longman and Braddon shows big gains for Labor among higher-income groups in safe seats, but corresponding gains for the Coalition among lower-income, older voters clustered in marginal seats where small swings make a lot more political impact.

Labor’s campaign among Catholic parents paid dividends for Susan Lamb in Longman but, again, Catholic voters tend to be bottled up in safe Labor seats, while tax cuts for small business, the National Disability Insurance Scheme rollout and Labor’s tampering with retirement incomes have been big vote winners for the government in marginal seats, especially in the bush.

In other words, Labor is likely to need more than 51 per cent of the national two-party-preferred vote that it is now recording in opinion polls to win next year.

A national majority of votes in opinion polls or elections is a great thing to have but it doesn’t necessarily mean the leading party wins a majority of seats, as former Coalition prime minister John Howard learned in 1998.

On Super Saturday we had significant contests in three seats: Mayo, Braddon and Longman.

Let’s get Mayo out of the way first. It’s a middle-class, professional, commuter seat with quite a few retirees and small business types, which typically should return a comfortable majority for a small-L Liberal candidate.

But typical Mayo voters don’t wear pearls to work, they don’t get dropped off in Dad’s Maserati, their mum and dad probably voted Labor as often as not, and they don’t mind other aspirational incomers to the lovely Adelaide Hills who are just like themselves.

As the polls predicted, Mayo was won by sitting Centre Alliance MP Rebekha Sharkie, who expected to work hard for the seat rather than inherit it. In the end, this outcome was a surprise only to Georgina Downer, the Coalition candidate and daughter of Alexander, the former MP.

Since becoming Prime Minister, Malcolm Turnbull has had to put up with some pretty ordinary candidates and campaigns in key marginal seats. Which brings us to Longman and Braddon. In both of these seats, former Liberal MPs had a personal vote of a couple of per cent at the expense of Labor in 2016. We’d expect this 2 per cent personal vote to be returned to the ALP at the by-elections, then doubled to 4 per cent by a personal vote for the new ALP members, Justine Keay in Braddon and Lamb in Longman.

This reshuffle of personal votes for new MPs would add to 4 per cent and is quite separate from any protest vote against the government. The bottom line is I would not be surprised by any by-election swing towards the new ALP MPs in these seats of 4 per cent or more, as this just shows a rearrangement of the furniture, rather than impending disaster.

Some over-egged poll predictions, however, enhanced expectations of a historic Liberal win in one or both of these seats. These proved unrealistic in Longman, but not so much in the Tasmanian seat of Braddon. The result in Braddon after preferences was pretty close to the poll predictions and showed virtually no swing. This was a strong result for the government.

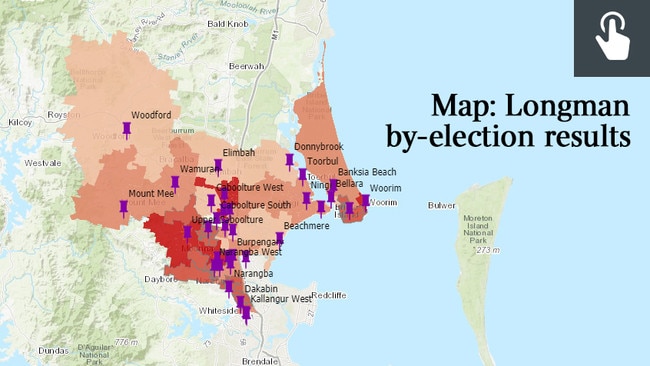

The result in Longman after preferences showed a swing of 3.6 per cent to the ALP, which was typical of the sort of result seen in a by-election. It could have been a lot worse for the government, as Liberal National Party candidate Trevor Ruthenberg suffered several mishaps on the campaign trail, to put it politely, and the ALP was aided by the presence of a One Nation candidate who siphoned off more primary votes from the LNP than he returned in preferences.

The range of 2PP swings to the ALP across booths in Longman went from minus 4.7 per cent to plus 9.1 per cent, with an average of 3.6 per cent. The range in Braddon to the ALP across booths went from minus 5.9 per cent to plus 17.8 per cent, with an average swing to the ALP of plus 0.1 per cent.

This is a range across both seats of about 24 per cent, so there’s plenty of scope to look for demographic differences in the combined booths and also at any variation in these patterns between the two seats. Remember, it’s this range of swings, rather than the average swing, that’s more important in projecting by-elections and determining who wins elections.

When we look at common trends to these two marginal seats on Super Saturday, we see that both showed strong swings to the ALP among booths dominated by the higher socio-economic status group of well-paid and better-educated professionals living in bigger, five-bedroom homes. This was consistent with previous by-elections and with our working hypothesis, following Bennelong and New England.

Conversely, both seats also showed strong swings to the Coalition in areas containing lots of lower socio-economic status families, with lower education levels, living in less expensive homes. These included many families on welfare benefits such as carers, disability benefits, single parents or Newstart. I’d be guessing here, but it looks as if the NDIS may be paying dividends for the Coalition rather than to Labor. In politics, memories are short and voters don’t do irony.

There were also many semi-skilled, blue-collar workers in these groups swinging to the Coalition, such as miners or machine operators or hospitality workers, as well as women in white-collar administrative support jobs.

Nationally then, the outcome for the Coalition parties, at this stage of the election cycle, is a strengthening of their support among lower SES seats in the remote and rural seats and in urban migrant seats.

To evaluate the impact of this demographic on next year’s election, we ranked all 150 seats by increasing SES scores to see which seats were likely to swing more to the Coalition, then we checked how many of them were marginal.

The top 20 on this list with the lower SES scores tend to be safe seats for the Nationals or for the ALP, with the only marginal seats being Labor’s Braddon and Lyons in Tasmania or the Nationals’ Page in NSW.

Swings to the Coalition among low SES voters in these 20 seats would thus see Page reinforced next year and put the Liberals back in contention to win the two Tasmanian seats. Further down the list, it also would shore up narrow Coalition 2016 majorities in Gilmore in NSW and Flynn in Queensland, and give it a second shot at Longman, presuming the LNP could find a strong local candidate in a hurry.

The challenge for the Coalition is that One Nation also performs well across these low SES seats and the Nationals have yet to realise that flirting with One Nation will always result in them losing more primary votes to Labor than they win back in preferences.

For the ALP, winning lots of votes in the high SES rich areas is a bit of a bust. If we rank the top 20 federal seats by decreasing SES, we find 13 held by the Libs, six by Labor and one by the Greens. All but two are relatively safe.

The ALP would have a better show of winning back the seat of Brisbane from the LNP’s Trevor Evans, and my own marginal seat of Griffith would be made safer for the local MP, Terri Butler. Mind you, the LNP doesn’t seem to have a candidate here yet.

In both of these Goat’s Cheese Circle Brisbane marginals, flirting with One Nation anywhere in Queensland basically just torches the Coalition’s 2PP vote.

The summary here is the Coalition benefits more from a reshuffling of its support down the SES spectrum, as there’s more marginal seats to be gained or protected at the lower SES end than at the top. Think of it as trickle-down politics.

The story doesn’t end here with the Braddon and Longman swings. While they had some demographic swings in common, they were separate campaigns run across two states and there were bound to be some key differences.

Longman was targeted by a very well-funded Labor media campaign focused on the final week, which was particularly critical of commonwealth policy on Catholic school funding. The Liberals focused on Labor’s threats to retirement incomes and tax cuts for small and medium businesses.

Labor’s campaign in Braddon seemed less frenetic and I saw no reports of a Longman-style campaign against Catholic school funding. However, the Braddon Labor candidate benefited from the preference votes of the local fishing fraternity channelled from local renegade fisherman Craig Garland, while the local Liberal state government appeared to be still relatively popular.

The analysis of results by booth showed the ALP’s big-spending campaign in Longman shored up its support among traditional Labor voters and among Liberal voters who swung to the ALP for the first time in 2016. We model all historic 2PP votes for the ALP and Coalition, so we have some idea of long-term trends and of the impact on votes of each of the leaders.

ALP voters in Braddon went back to the Liberals, in Longman they did not.

To cancel out this swing back to the Liberals in Braddon, the ALP gained big swings in booths dominated by self-employed farmers or fishermen, thanks, we presume, to preferences from Garland.

The campaign in Longman from Labor and local Catholic schools arguing for increased funding from the commonwealth drove a big swing to Labor in booths containing both Catholic parents of young students at local Catholic primary schools.

This was not just an ecological correlation as Catholicity also appeared in our regression modelling as a significant driver of the swing to Labor across Longman booths, even with other drivers taken into account.

Cancelling out some of this swing to Labor in Longman from the big group of local Catholics was a swing to LNP candidate Ruthenberg from the self-employed living off income from an unincorporated business or older locals in their early 60s who had paid off their home loan and were approaching retirement while drawing on income from company investments.

So the Catholic vote walloped the LNP in Longman and it could have been a lot worse without increased support from small family businesses and from Australians about to retire.

The tide in Braddon appears to be going out on the federal Labor vote among its long-term Tasmanian supporters and the Labor candidate was rescued by the strategic preferences from Garland.

How do these differences play out on the national stage? Well, our scenario would see a swing to Labor from Catholic parents of kids at Catholic schools versus a swing to the Coalition from older people approaching retirement. Labor would have to run particularly well-funded campaigns, as it did in Longman, which could stretch its resources somewhat.

When we rank all the present federal seats by Catholicity, we find the top 20 dominated by Labor seats, including those of Bill Shorten and his Treasury spokesman, Chris Bowen.

Ten of the 11 seats here are safe for Labor, with the only exception being Lindsay on 51 per cent 2PP, represented by Emma Husar. Husar is now subject to speculation she may be the cause of the next by-election. Of the remaining nine strong Catholic seats, only Reid, held by Craig Laundy by 54.7 per cent, could be considered marginal for the Coalition.

Moving further down the list, the Queensland LNP seats of Dawson and Capricornia are marginal and one in four local voters is Catholic, so these could come into play if the Queensland LNP doesn’t lift its game before next May. #This is a reasonably big if.

The seats ranked according to 60-64 years look a lot more significant. Fifteen of them are held by the Coalition and five by Labor. There’s also a lot of overlap with lower SES seats.

Of the 15 Coalition seats, four are marginal — Gilmore in NSW, Mayo in South Australia and Indi and Corangamite in Victoria — and these would be shored up for the Coalition by a rise in support from voters transitioning to retirement and concerned at Labor’s plans for their retirement savings.

On the Labor side, the marginals include Lyons and Braddon in Tasmania and Richmond and Eden-Monaro in NSW. Further down the list we see Bendigo in Victoria. These are potentially target seats for the Coalition in 2019.

In summary, Catholic parents cranky at the government tend to be found in safe seats, rather than marginals, whereas the older voters transitioning to retirement and worried about Labor’s retirement policies tend to be found in marginal seats, some of which could be won by the Coalition next election.

What this means in a strategic sense is that on our present trends from the by-elections held in Bennelong, New England, Mayo, Braddon and Longman, and in the opinion polls, Labor is picking up more wasted votes in safer seats than it is losing in key marginal seats, and this means it is going to need more than 50 per cent of the national 2PP vote to win more than 50 per cent of the seats in the House. The 51 per cent we’re seeing consistently for Labor in the polls now may not be enough for Shorten to become PM.

This fate befell Labor’s Kim Beazley in 1998 when he won 51.4 per cent of the vote and still failed to win a majority of seats, and it can happen again.

The ALP tactical campaigning in the by-elections has been a bit of a masterclass really, and credit should go to Shorten for getting away with it for so long. But strategically he has pulled the wrong rein by taking on the boomers and their retirement savings.

As for the Coalition, you may have noted something missing from this analysis, and that is the group of middle to upper-income earners swinging to the Coalition as a result of Scott Morrison’s personal income tax cuts.

That’s because they’re not swinging to the Liberals but to Labor. If they believed the Treasurer’s promises or could feel the jingle in their pockets, there would be daylight now between the votes for the Coalition and the ALP.

You just have to shake your head at this performance. Fair dinkum, Casper the friendly ghost would have more visibility selling this tax policy than the Treasurer.

And while we’re on the subject of losers, spare a tear for poor old Anthony Albanese. In the days before the by-elections, he was modestly declining to run for the leadership if Labor underperformed — as expected — and protesting his loyalty to Shorten, which all caucus members knew means he was running hard.

The only person more delighted than Shorten by the Super Saturday results for Labor was Bill’s deputy, Tanya Plibersek, who realised that if Bill went, well, so did she, as the idea of two lefties from two adjoining, super-rich, Sydney green-Labor seats getting elected prime minister and deputy prime minister was never going to fly.

Well, Bill and Tanya are still there and the odds of a last-minute coup have receded, for the time being.

This should bring some relief to Turnbull, although it does mean he has to deal with some pesky challenges of his own.

Pacifying Catholic parents would be top of the list and second from the top would be trickling down the company tax cuts for big business to small to medium businesses or to families.

And what would he stand for if he abandoned tax cuts for the big end of town?

Well, getting re-elected for a start. Which is, after all, the primary requirement for a PM.

John Black is a former Labor senator for Queensland and is chief executive of Australian Development Strategies. His election profiles and maps can be found at www.elaborate.net.au.