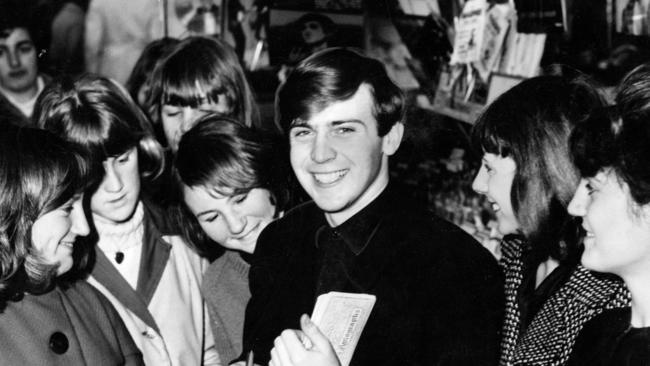

It Ain’t Necessarily So gives young Normie Rowe debut top 10 hit

It Ain’t Necessarily So was written for a stage show based partly on the life of a disabled beggar.

(Written by George and Ira Gershwin with Heyward DuBose — reached No. 1 on the charts, June 1965)

Brian Epstein famously took an interest in the Beatles when two customers in one day entered his shop asking for the band’s latest single. Two people couldn’t be wrong, Epstein thought.

Normie Rowe’s career was similarly launched when a cautious record company ordered just 50 copies of his first single, It Ain’t Necessarily So.

In April 1965, an enthusiastic Rowe turned up unannounced at the door of Bill Duff, Festival Records’ Victorian promotions manager, to talk about a song he had just recorded.

“He was a slightly chubby young fellow with what I can only describe as a Prince Valiant haircut,” recalls Duff, bemused that the young man, at the height of Beatlemania, would turn to a Broadway musical for his debut record. Rowe was 18. His new song began life in a book written by a long dead, and largely forgotten, American born in 1885.

The singer had never seen the stage show to which the song gave birth and did not sing it using the original black ghetto patois of a drug-dealing pimp cynically questioning the Bible’s authority.

It Ain’t Necessarily So has been recorded by some of music’s biggest names — Louis Armstrong, Bing Crosby, Paul Robeson, Frank Sinatra, Aretha Franklin, Bobby Darin, Nat King Cole, Cher, Sting, Cab Calloway and even the Moody Blues — but, curiously, it has only been a top 10 hit in Australia.

Duff thought the record had merit and took copies around to radio disc jockeys who liked the unexpectedly sophisticated, multi-layered recording and played it constantly over the weekend. On Monday morning, Festival received calls from its two key city record outlets: each wanted 25 copies. Festival was out of stock and Rowe was in luck.

But It Ain’t Necessarily So remains perhaps the most unlikely pop hit Australia has witnessed.

Its story dates back to DuBose Heyward’s writings based on his early life on the Charleston waterfront, where he and his sisters and mother lived alongside its poor blacks.

Heyward’s mother, a sometime poet and author, was fascinated by a creole language they spoke called Gullah — a complex mix of English and West African — an enthusiasm she passed on to her son.

She would sometimes write about the history of her town and in 1912 published a small volume, paternalistically titled Songs of the Charleston Darkey.

Heyward wrote his book after seeing a newspaper report about a disabled beggar he knew as Goat Sammy — Sammy Smalls.

Most of South Carolina seemed to know Smalls, who moved about Charleston in a cart his father made for him, drawn by a goat. They parked on corners selling peanuts and pencils, recalled one of his 26 brothers and sisters.

In 1923, Goat Sammy shot and injured a former girlfriend. Heyward, who’d moved away and married playwright Dorothy Kuhns, saw the news in The Charleston News and Courier and it brought back childhood memories of the extraordinary range of characters — fishermen, stevedores, drug dealers, pimps and police — whose neighbourhood he once shared and whose lives were framed by poverty and the church.

That they communicated in an exotic language — although he is reported to have known it well — only added to what Heyward described as the “mystery and movement of Negro life”.

Smalls became the character Porgy in the 1925 novel of that name. Dorothy instantly saw its potential as a theatre piece with its potent mix of love, sex, violence, survival and intrigue. She told her husband so, but he disagreed.

She worked away on what Heyward understood to be a detective novel, but it was her reimagining Porgy for the stage. When he saw what she had done a light (finally) went on.

Porgy as a play premiered in New York on October 10, 1927, with black actors, at the Heywards’ insistence. On Broadway at the time, black characters might still be portrayed by white actors in blackface.

It was a success, toured the US twice, went to London and returned for more performances.

Its transition to an opera was overseen by George Gershwin and his brother Ira, but the words to the songs came predominantly from Heyward. He hadn’t written songs before that anyone could recall, but off the bat appears to have come up with Summertime and, at least in part, It Ain’t Necessarily So (although clearly it was George Gershwin who hinted at an ancient Jewish Torah prayer in the melody).

Porgy and Bess opened on Broadway in 1935 and was quite successful, but from the outset it was tangled in racial politics. Was it condescending of black Americans? Did it stereotype southern blacks as lazy, often criminally minded people who easily resorted to violence? For many, no doubt, there were just too many blacks on the stage.

When German troops marched into Copenhagen to begin the occupation during World War II, Porgy and Bess was being performed at the city’s Royal Opera House. Next day, the Nazi SS threatened to bomb the theatre if the show continued, opposed to an opera by Jews about blacks. The shows were cancelled. But the Danish resistance thereafter jammed Nazi propaganda broadcasts and Hitler’s speeches with a recording of It Ain’t Necessarily So in Danish.