Innings over, hints Cricket Australia umpire

Cricket Australia’s chairman David Peever looks stumped and should walk.

The venerable mining chief John Ralph used to tell this story to prospective company chairmen.

One day, a chairman was handing over to his successor. “If you get in trouble, go to the safe,” he said. “In it, you’ll find two numbered envelopes. They’ll help you.”

So the new chairman took office, duly faced his first crisis, went to the safe and opened the first envelope. Inside was a piece of paper that read: “Blame me”. So the chairman heaped blame at his predecessor’s door, and the crisis duly abated.

It worked so well that when a second crisis eventually broke out, the new chairman could hardly wait to return to the safe. What pithy wisdom would the second envelope impart? Inside was a piece of paper that read: “Prepare two envelopes”.

Which brings us to another mining man, coincidentally from the same group where Ralph was a tribal elder. David Peever spent 27 years at Rio Tinto before becoming a member of the inaugural “independent” board of Cricket Australia in 2012, succeeding to the chairmanship in 2015.

Ralph’s observation that chairs will generally be indulged one crisis but seldom more is presently being put to the test.

Last year, Peever was the key string-puller in CA’s breathtakingly maladroit campaign to end the revenue share agreement with the Australian Cricketers Association that had underpinned 20 years of sporting industrial peace.

Now he finds himself embroiled in another fiasco largely of his own making. It was not Peever who applied sandpaper to a cricket ball at Newlands — he was, in a rare moment of good timing, flying in the opposite direction, away from South Africa.

Peever did, however, put faith in an independent review of the “culture and governance” of CA by Sydney’s Ethics Centre — and independent it sure is.

Simon Longstaff’s 147-page report is detailed, blunt and often scaldingly critical. In the case of Newlands, Longstaff concluded, CA was culpable for its failure to “create and support a culture in which the will to win was balanced by an equal commitment to moral courage and ethical restraint”.

More generally, CA was widely regarded as “arrogant and controlling”, perceived to “say one thing and do another”, and understood to be a place “where people struggle to say ‘no’ to people in positions of power and influence”.

The organisation would need “to address the perception that it is (or believes itself to be) the sole or principal custodian of Australian cricket”.

Like the Australian team in March, then, CA has been jolted to a realisation of its pent-up unpopularity. In mitigation, one might observe that there but for the grace of God would go many a large Australian sporting organisation. How would the cultures and governance of various football codes emerge from such scrutiny?

The difference was, however, that CA gave The Ethics Centre the keys to the shop, perhaps in expectation of a relatively gentle ride. One of Longstaff’s key findings is that really only CA’s board and senior executive think they are going well — nobody else.

When CA did not get what it bargained for, the report appears to have stalled for some weeks. One reason for this, it is now apparent, was legal. As published, the review features no fewer than 38 redactions to save the blushes of individuals named, causing it to resemble a copy of Ulysses as expurgated by the Kansas Board of Education.

Were there other reasons? Suffice to say that the delay was long enough for CA to appoint as its new chief executive Kevin Roberts, Peever’s preferred candidate, and to hold its annual meeting last Thursday, at which CA’s state association owners re-elected Peever for a second three-year term.

Then, and only then, were those associations permitted to partake of Longstaff’s unsparing judgments — to which some of them, as respondents to his interviews and questionnaires, had contributed.

As the state chairmen sat there watching Peever hem and haw at Monday’s review press conference, how many of them experienced buyer’s remorse? Because it was, frankly, mortifying.

Peever’s corporate career was mainly a corridor affair — he was instrumental in the lobbying against Labor’s 2010 mining tax.

He has never looked particularly suited to a public-facing position; in the role of cultural commissar he now appeared not only acutely out of his depth but to incarnate the attitudes Longstaff described.

He spoke of “respecting” the findings, while evidently some distance short of accepting them. He claimed not to be “embarrassed at all”, in the next breath quibbling about “reality” and “perception”.

In one rhetorical flight, Peever invoked “the light on the hill”, which he defined “for all of us … that we want cricket to be the best that it can be”. He stopped short of asking cricket fans to maintain their rage and enthusiasm.

Australian Associated Press reported him afterwards as “adamant that he is going nowhere”. Quite.

Nothing being quite official until it happens on television, Peever concluded his day with a final mea minima culpa on the ABC program 7.30 in which Leigh Sales made him resemble one of those inflatable clowns weighted in the bottom with sand that bounce upright when punched in the face. “The work was never about, umm, ahh, dwelling on negatives,” Peever volunteered, apropos of nothing. “This is a very important day for cricket and we are moving forward from here.”

Sales asked: “If you don’t want to address the negative, how do you move forward from here?”

Peever continued in his impervious monotone: “Indeed, we’re not dwelling on the negatives. But we’re, umm, arr, taking very seriously what has been written in the review and, indeed, 42 recommendations from the review, and already many of those are being actioned.”

Sales continued with the simplest question of all: “How can the very same people who presided over this toxic culture now be the ones to change it, particularly when, as the report explains, you’re the only people who couldn’t identify the problems?”

Peever’s was not an answer: “Yeah, cultural change comes about by understanding where some of the gaps are. This report identifies those gaps. And we will certainly, as I said, be using it to improve the game.”

The clincher was Peever’s contention that cricket was strong despite having experienced a “hiccup in South Africa”. If it was merely a hiccup, what was this exhaustive review process about? If it was merely a hiccup, why have Australia’s best two cricketers been sidelined for a year? Train wreck? This was the Southern Aurora colliding head on with the Spirit of Progress.

Peever’s name, incidentally, does not appear in the review, leaving readers to wonder which redactions it may lurk beneath, because his influence certainly registers.

Longstaff specifically addresses the contribution to the souring culture of last year’s collective bargaining negotiations between CA and the Australian cricketers Association, which involved “tactics described as arrogant” and were “cited as having contributed to dysfunction in relationships between CA and the players”.

This pointless and destructive campaign was to a significant degree Peever’s handiwork; it also acted as an opportunity for his protege Roberts to audition to succeed James Sutherland.

Longstaff elsewhere makes mention of a bullying culture at CA “said to be evident in other stakeholder relationships” and in “the tactics employed when negotiating commercial outcomes”, to which “a blind eye” was turned. No more spectacular example of the tactics employed when negotiating commercial outcomes exists than Peever’s March intervention in the course of television rights negotiations, when he lambasted CA’s broadcast partner Network Ten as “not prepared to challenge their operating model to be anything other than bottom feeders”.

Peever’s scolding message to Armando Nunez, president of Ten’s owner, CBS, subsequently became public: “Unfortunately your team has completely messed this up. I expected much more given our discussions and the unique position we were affording 10. Franky (sic), the tactics are appalling on a number of levels.”

Privately, according to fellow director Bob Every, who subsequently quit the board protesting his chairman’s “substandard” leadership, Peever offered to resign at the time, but in such a way as to cast doubt on his sincerity.

Publicly, Peever expressed regret, with the qualification that the message had been sent “in the context of a negotiation” — the commercial counterpart to the time-honoured sledging cliche of “what happens on the field stays on the field”.

Although only time will tell what the Longstaff review means in the longer term, some are already exploring its potential — including the cricketers trade union.

Longstaff wants CA to “establish a constructive working relationship involving a mediator” with the ACA, and to commence “confidence-building measures”, summoning up the image of Peever falling backwards into association president Greg Dyer’s arms.

For the time being, rapport remains elusive. Dyer was yesterday arguing that the review’s “new evidence” justified a relaxation of the penalties imposed on Steve Smith, David Warner and Cameron Bancroft, which are, as has been widely observed, significantly out of proportion with those clapped on previous ball manhandlers.

Prima facie the case is good; second impressions are somewhat less flattering.

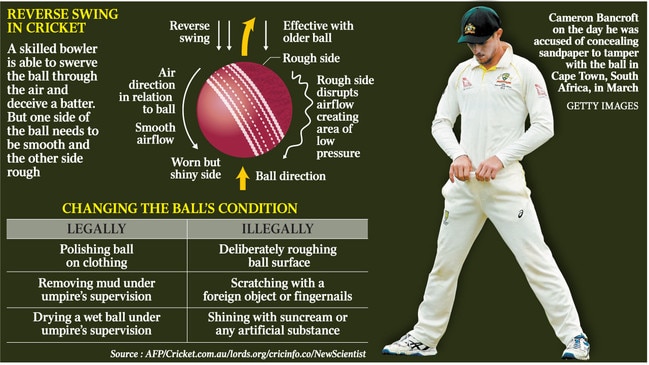

Australia’s ball tampering at Newlands was uniquely flagrant and egregious. There is some ambiguity about the use of a fingernail or the application of mint-flavoured saliva; Bancroft, with the connivance of Warner and acquiescence of Smith, premeditatedly undertook a clearly illegal practice, causing teammates, as well as the game, needless distress and financial loss.

The suspensions, furthermore, were not imposed for ball tampering alone — the three of them were also sanctioned for evasions after the fact, at the press conference and with the investigator. They had the opportunity to appeal and did not take it.

Longstaff’s review is helpful context rather than “new evidence”, and context is of necessarily limited value. We now understand, thanks to the Hayne royal commission, that ripping people off, dead and alive, was a cultural norm at banks and insurers. But this makes no difference to our distaste for individual depredations.

The public seemed satisfied with the sentences on the three cricketers six months ago, and if fury has abated it still lurks beneath the surface.

That said, it would be a good deal easier for CA to reinforce the players’ accountability were its board and officers also held to account in material terms.

That they have not merely reinforces Longstaff’s view that “the same standards (as apply to players) do not apply to those who administer and govern the game”.

Indeed, they’re hardly donning hair shirts at Jolimont. Sutherland concluded his 17-year tenure as chief executive last week, leaving the cricket system financially richer yet in other respects spiritually weaker, while the ranks of well-paid executive general managers remain unchanged.

A new deputy chairman and heir apparent has been appointed, Earl Eddings from Victoria, which, looking forward, implies that CA’s board will be chaired by a wealthy, conservative, middle-aged, suit-wearing white man out to 2024.

The advent of the independent board six years ago was meant to expose CA to the winds of change and the rigours of the marketplace. Yet there is a case it has simply installed a new elite, less accessible and accountable than before, allowed for the unthinking assimilation of corporate values, for steady deterioration in the working environment, for flimsier relations with stakeholders, and, most publicly, cricket’s public denigration. “I serve as chairman at the pleasure of the board and I serve as a director at the pleasure of our owners, the states,” Peever reminded all present on Monday.

A group of people, in other words, much like him. The game? The public? The nation? The spirit of cricket? Not so much.

Yet on what we have seen this week, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that David Peever should set about preparing two envelopes.