Federal Circuit Court in controversy over Sandy Street

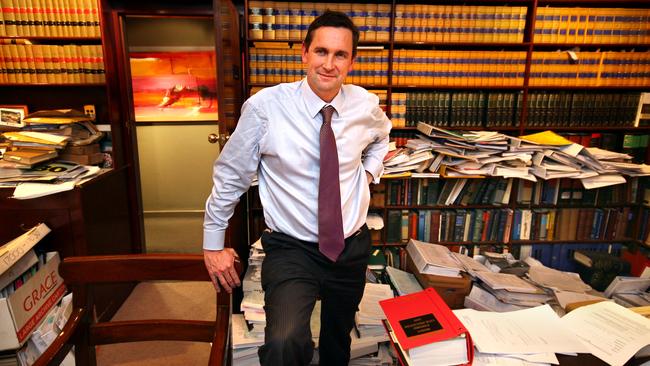

Federal Circuit Court judge Sandy Street is part of judicial royalty, but his methods have raised eyebrows among peers.

It is 10.45am in Federal Circuit Court judge Sandy Street’s courtroom and already a man has been declared bankrupt and two Chinese men seeking protection visas have had their claims for judicial review rejected.

The bankrupt has not appeared in court; his wife says the man is too depressed to attend.

“I won’t be granting an adjournment and you can go to the back of the court. You’re not entitled to appear,” the judge tells her.

Judge Street has a habit — which can be unsettling — of standing at the bench, which allows him to read electronic court documents on two computer screens without hurting his neck. He also stands at his desk in chambers. This Tuesday morning is no different, and Judge Street is on his feet as he delivers his ruling ex tempore, or on the spot, about three minutes later.

“Proceedings in this court must proceed with due expedition,” he says. “I’m satisfied on the evidence before the court that the respondent is unable to pay his debts as and when they fall due and that this is an appropriate matter to make a sequestration order.”

It has been three years since Judge Alexander (Sandy) Whistler Street SC was appointed to the Federal Circuit Court by former attorney-general George Brandis.

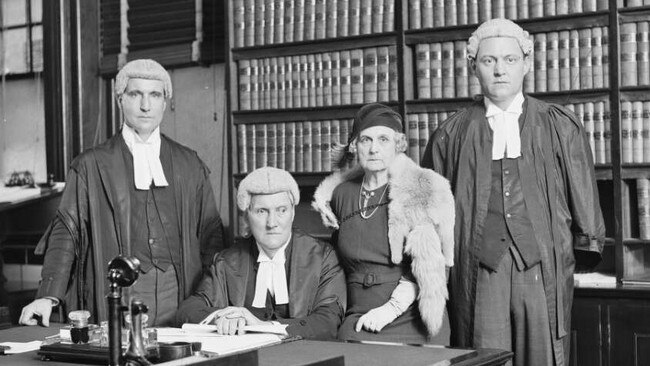

He is a descendant of the closest there is to NSW legal royalty. His father, Sir Laurence Street, was NSW chief justice, as was his grandfather and great-grandfather, and his grandmother was human rights campaigner Jessie Street.

His sister, Sylvia Emmett, is also a Federal Circuit Court judge, and her husband, Arthur Emmett, is a judge of the NSW Court of Appeal. The next generation is also plying their trade in the law.

But some would say Judge Street’s record on the bench has been less than majestic.

While the Federal Circuit Court declines to say exactly how many of his judgments have been overturned on appeal, The Australian has uncovered at least 47.

It’s not necessarily the number that is striking (many more of his decisions have been upheld than reversed), but the way his decisions have been criticised by the appeal judges at times for denying litigants procedural fairness or failing to give proper reasons in some cases.

More than once his decisions have been criticised even when his orders have not been overturned.

In one case, the appeal judge said “far greater specificity would have been preferable” in Judge Street’s reasons, saying “ex tempore reasons may sometimes achieve expedition in decision-making at the expense of justice”.

Judge Street’s decision drew disapproval from the Federal Court last month in a case involving a Tamil asylum-seeker whose brother and sister had disappeared in 2009 and are still missing. The Immigration Assessment Authority, which reviewed the man’s claim, had accepted he had been threatened “with the same fate” as his siblings if he continued to complain about their disappearance.

Justice John Griffiths found a “constructive failure” by Judge Street to exercise his jurisdiction, saying he “never grappled directly with important elements of the appellant’s primary claim”, and his reasons — also delivered ex tempore — amounted “to little more than assertions or conclusions”.

“It is proper to acknowledge that the Federal Circuit Court of Australia’s migration jurisdiction is a high volume and challenging jurisdiction,” Justice Griffiths said in his February 6 judgment.

“Equally, however, it must be recognised that that court is exercising an important judicial review jurisdiction and litigants are entitled to expect that the well-established features of the judicial process will be provided. Those features include not only the requirements of procedural fairness but also that the court will provide adequate reasons for its decision and properly address fundamental aspects of the parties’ respective cases.”

Justice Griffiths returned the matter to the Federal Circuit Court for rehearing by a different judge because the “absoluteness” of Judge Street’s findings or “more accurately, assertions” gave rise to “considerations of apprehended bias” in the mind of the reasonable observer.

Since his appointment on January 1, 2015, Judge Street has finalised an extraordinary number of cases — more than any other judge of the court. He has delivered about 1370 published decisions. The other eight Sydney general federal law judges combined, delivered about 2290 in the same timeframe.

In a jurisdiction struggling with a tsunami of family, migration and other legal disputes, Judge Street is one of the only judges making real inroads into the court’s growing backlog of cases. But there is a balance to be struck between efficiency and a fair hearing, and some migration lawyers say Judge Street can be too quick at times to reject legal arguments.

In any event, when Federal Court appeals are launched and cases are returned to the Federal Circuit Court for rehearing, an extraordinary amount of court time and legal fees are wasted.

In 2015, Judge Street was accused of apprehended bias after it emerged he had rejected 252 out of 254 migration appeals in a six-month period. The full Federal Court rejected that claim. However, documents filed in court, and revealed by the ABC, showed that while the success rate of migration applicants in Judge Street’s court was 0.79 per cent, other judges had found for applicants in 10 to 12 per cent of cases.

Prominent refugee lawyer David Manne is not willing to comment on Judge Street or any individual judges but says that, for applicants in the court’s migration jurisdiction, the stakes could not be higher.

“If the wrong judgment is made, there is the very real risk of someone being sent back to torture or death. That’s the reality here,” he says.

He says the Immigration Minister and his delegates, and the bodies set up to review their decisions, “do not always get it right”.

“That’s why we have, under our legal system, this fundamental safeguard that someone can seek review in a court,” he says.

“Given the gravity of the matters at stake, it is absolutely fundamental that people receive a fair hearing on appeal.”

When he first joined the court, Judge Street threw out a number of cases at their first court date on an improper basis, in some instances despite warnings from the opposing side, prompting some successful appeals.

The Federal Court took a dim view of this approach, warning it “should not occur again”.

Rule of Law Institute of Australia vice-chairman Malcolm Stewart tells The Australian that even if a litigant is unsuccessful, it is crucial the party believes they have had a fair opportunity to present their case and it has been properly considered, or it breeds resentment.

“That resentment may result in unsuccessful litigants, and others, criticising individual judges and the judicial system generally,” he says. “Ensuring litigants have had a fair opportunity to present their case and that it has been given due consideration is important to the general level of respect and confidence we have in the system.”

If a decision is wrong, a litigant can appeal. But for migrants with poor English and limited funds, it can be a daunting prospect to launch a Federal Court appeal when faced with an adverse costs order.

Judges are appointed until the age of 70 and cannot be removed other than for proven incapacity or misbehaviour by the governor-general on an address from both houses of parliament.

In Australia’s history, only one judge has been sacked: Queensland Supreme Court judge Angelo Vasta in 1989 over allegations of improper tax arrangements.

Chief judges can put in place administrative arrangements to manage a judge, such as taking them off hearings. But there are few other powers at their disposal. They cannot force a judge to attend training, although the National Judicial College of Australia recommends all judges attend five days of ongoing education a year.

It is understood a registrar often handles Judge Street’s cases on their first court date, which is common practice among general federal law judges.

University of NSW associate professor of law Gabrielle Appleby says a federal judicial complaints-handling system set up in 2012, which allows a chief judge to investigate a complaint or set up a conduct committee, is directed only at handling complaints about misbehaviour or incapacity.

She says a robust judicial appointments process is critical “to get the right people on the bench in the first place”.

“This idea in Australia that still remains so strong is that judicial appointments are the gift of the executive,” she says. “In most Western democratic systems, they now have independent merits-based, criteria-based appointment systems.”

She points to Britain and Canada, which each have a judicial appointments commission, comprising judges, government representatives and lay people, to assess candidates and make recommendations about appointments.

She says this is intended to ensure the most suitably qualified people are appointed to the bench.

Judge Street was tapped to join the Federal Circuit Court on December 11, 2014, in a batch of appointments that drew criticism because of the number perceived to be close to Tony Abbott and the Liberal Party.

This included Gary Humphries, a former Liberal senator appointed to a plum $460,000-a-year role as deputy president of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal.

There were three announced for the Federal Circuit Court that day. One was Ian Newbrun — a friend of Abbott, who was appointed to handle family law cases but had limited family law experience.

He caused such consternation among family lawyers there were efforts to move him out of the family law jurisdiction, but he successfully resisted.

The other was former prosecutor Sal Vasta, the brother of federal Liberal MP Ross Vasta and the son of Angelo Vasta.

Judge Street, in one sense, was a catch for the Federal Circuit Court because he was a silk. He had been made an SC in 1996 and had served as a deputy head of the Sydney Naval Legal Panel. He also had served on the NSW Bar Council and previously had provided advice to the Liberal Party.

However, he also had a reputation at the bar as a “renegade”, bringing creative legal arguments to court — some of which were successful, some of which were finessed by the judges hearing them, and some of which just didn’t fly.

Some big wins had brought him to prominence. In 2009, Judge Street succeeded in having the government’s military justice system declared unconstitutional by the High Court, while representing a naval officer accused of “teabagging”. Earlier, he had successfully challenged Queensland bar rules that prevented competition from interstate rivals.

However, Judge Street also had attracted unwelcome attention when his former mother-in-law launched legal proceedings to recoup more than $500,000 she had lent to him and his ex-wife, a commercial lawyer turned singer, to help pay the mortgage on their Vaucluse home.

He revealed he was facing potential bankruptcy, owing $230,000 to the Australian Taxation Office, and was being forced to sell his share in his barristers chambers.

But the gossip did not prevent his judicial appointment the following year.

Australian National University professor Margaret Thornton says more should be done to ensure the best candidates are appointed to the bench, rather than tapping members of the boys’ club.

She points to a discrimination case in which Judge Street compared childbirth to buying a bag of chips — another decision criticised on appeal — and says it is disappointing there are not more female judges.

Thornton says it “looks very bad” for the government when it appoints judges who attract criticism at times. But she says public critique is one of the only ways to hold judges to account.

Back in Judge Street’s courtroom, above Sydney’s busy William Street, one of the Chinese asylum-seekers is trying to make out his case.

The man says he was threatened by officials for complaining about the lack of compensation paid to farmers when a highway was built through their village and farmland.

Judge Street takes about 10 minutes to hear the man’s application for judicial review before beginning to deliver another ex tempore decision. He then asks the man if there is any reason he shouldn’t make an adverse costs order for $5600.

“I lost the case, so I mean I don’t know how to put it,” the man says through an interpreter.

“I don’t regard that as a response in relation to the costs issue,” the judge says.

“I order the applicant to pay the first respondent’s costs.”

And then it’s on to the next case.