Farmers proud of ability to ride out ‘dry’ times amid drought mania

Agribusiness Australia CEO says the struggle of drought-hit farmers is being overblown and risks turning the sector into a charity case.

Tim Burrow is fed up with what he calls drought mania.

The pub nights of “parma for a farmer”, the interviews with gap-toothed five-year-olds giving their pocket money to save a starving lamb, the television celebrities exhorting Australians to dig deep and pensioners donating money they can ill afford to buy a bale of hay for a struggling cockie leaves the chief executive of Agribusiness Australia cringing and gnashing his teeth.

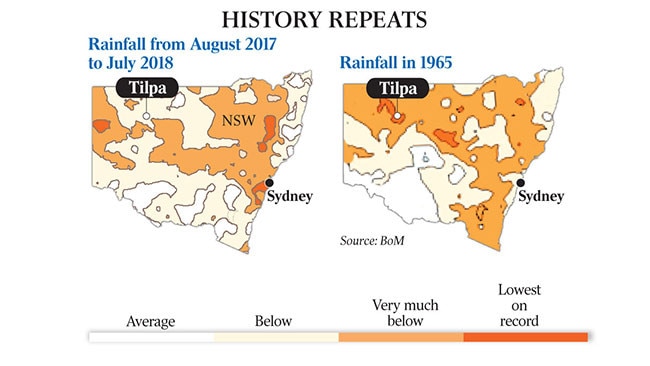

So, too, do the media reports describing the drought crippling NSW as the worst on record amid calls for it to be declared a national disaster.

“What on earth is going on?” says a frustrated Burrow, whose organisation represents Australia’s biggest agricultural companies, processors and exporters.

“It’s all got out of proportion and gone much too far.

“This is not the worst drought on record and only a tiny proportion of farmers, even in NSW where this drought is centred, are in desperate straits. Australia has always had droughts and always will have, but the vast majority of farmers are managing through it and coping fine.”

Burrow wants some balance to be brought back to the drought, especially its coverage by Sydney-based TV programs, before the reputation of a fast-growing modern industry that is trying to attract international investment capital is irreparably harmed.

He wants a more realistic view; a reminder that agriculture is a sophisticated $60 billion sector, that fewer than 1 per cent of farmers are in desperate drought-stricken strife, most states other than NSW and Queensland are having a good or average season and the financial impact of this so-called terrible drought will be less than a 10 per cent blip on the total value of annual farm production.

“Farmers who contact me say they are so over the media mania; that while we have to look after the small 1 per cent of farmers who are suffering — just as we provide a safety net for all Australians — the majority have planned ahead for dry times and are doing fine,” says Burrow.

“It’s unfortunate for a resilient industry that’s bigger than the gas sector if people see it as a charity and you have little old ladies giving $15 from their pension that they can’t afford to a farmer who should have managed things better and who probably is sitting on $1 million of assets.”

Burrow’s is a hard-nosed view of a terrible drought officially affecting 100 per cent of NSW and much of southern Queensland, and one that undoubtedly is causing hardship.

The stories of NSW farmers with no hay left to feed their sheep, cattle and horses and no cash left to buy food, fuel and toothpaste are all true.

But so, too, are the quieter tales of primary producers battling their way through the drought, selling cattle and sheep to bring in cash and reduce the grazing pressure on their bare paddocks, or cutting their losses with failed winter grain crops by “spraying them out” to preserve as much soil moisture as possible for a potential summer crop.

Then there are farmers such as Gill Sanbrook from Holbrook, just north of the NSW-Victoria border, who says drought is no longer a term that should be used in Australia. Instead, Sanbrook, who runs a 400-head herd of cattle at Bibbaringa, a 1000ha hill-and- valley farm north of Lake Hume, says she has been shocked at TV stories about farmers forced to shoot hundreds of starving sheep and appalled at the potential animal welfare backlash such images create.

“Farming doesn’t have to be — and shouldn’t be — like that,” says an Sanbrook, who has run her farm on holistic and “regenerative principles” for a decade, planting 70,000 trees, changing eroded creek beds into gently trickling tiered wetlands and altered paddock layout so her cattle graze on the same bit of land for only three to four days every six months.

The focus is on building up soil organic matter and carbon content and preserving as much water that falls as rain on the farm as possible in her soil.

In the process, Sanbrook has eliminated the need to drench her cattle for worms, eradicated the need for fertilisers on her pastures and has standing grass all year round in most of her 63 paddocks, despite having just half her usual rainfall this year.

“Debt and drought have led me here, and a sense that what we have been doing before wasn’t working,” says Sanbrook, who routinely makes hard calls to sell off or buy in cattle depending on long-term weather forecasts for the months and seasons ahead.

“I love being a primary producer but I’m a business; drought — or what I prefer to call dry periods — is not a natural disaster but a normal part of our climate and the key to farming in Australia is to be flexible and to manage the property to the conditions I am presented with.”

Wagga Wagga cattleman and part-time stock agent Steve Condell agrees that a key difference between farmers who are coping with the drought and those who are not (in southern NSW many farms have received less than a third of their annual rainfall in the past 12 months) is their decision-making ability, especially when under financial duress.

Research studies of personality type show farmers are much likelier than the average person to be conservative decision-makers: 57 per cent of them are sensing and judging personality types, according to the Myers Briggs test, compared with 42 per cent of the general population.

This creates a dominant farmer culture that is less likely to adopt new ideas, is generally resistant to change and in which decisions are based on precedent and past experience.

Condell’s experience in the past few months bears these studies out.

Many times recently he has arrived at properties to find farmers with no grass left in their paddocks and no hay or grain to feed their cattle and sheep, but frozen and unable to make the final hard decision to destock the farm completely or sell off valuable breeding stock.

He says now it is often left up to stock agents such as himself to ensure the tough but inevitable steps are taken, unfortunately usually later than they should have been made and often when livestock are in a poorer condition to sell for the top prices they once would have earned.

“It’s not that there wasn’t any planning — these people planned ahead for months — but this is the longest and driest spell on record; this is unknown territory for most farmers,” says Condell.

“It’s human nature; farmers hang on for as long as they can because of what they are used to. But the rainfall and seasons are changing. I go to their properties and still see them hoping the rain will fall next week.

“Mentally and financially people are at a point where they have never been before.”

With little relief or rainfall in sight this spring (the Bureau of Meteorology this week ominously forecast a September to November period more likely to be warmer and drier than normal) National Farmers Federation president Fiona Simson is left in the difficult situation of trying to temper the “drought mania” while representing the real needs of some farmers.

She is determined to avoid a “blame game”, whereby farmers pleading for hay and financial help in the face of the drought are somehow seen to be “bad” operators who should have made better farm management decisions.

Simson says particular circumstances, such as a recent farm expansion, taking on new debt, or a bushfire such as the Sir Ivan fire of February last year that burned farms around Dunedoo, Cassilis and Coolah in NSW’s central west, coinciding with a prolonged drought can spell financial hardship and desperation just as much as more acknowledged differences between farms such as size, farmer education levels, business attitude and financial resilience.

The NFF this month joined Rotary and the Nine Network to launch a drought relief appeal, which has raised more than $3 million from the public.

On Thursday, Simson announced the first appeal grants of $500,000 for the Lions Club’s “Need for Feed” program, which buys and trucks 10 big round hay bales to every drought-affected farmer who needs hay to keep livestock alive.

There was also $250,000 each for the NSW and Queensland Country Women’s Association branches, which are providing food hampers, shopping vouchers and personal “care packages” for hard-hit families, as well as the offer of paying up to $3000 of household bills.

Straight-shooting Simson confirmed yesterday the NFF had got involved with the drought appeal only because it wanted to “put the balance” back into the media coverage, which has spiralled out of control.

“The public has shown they are so generous and love and respect farmers, which is absolutely fantastic and so important when many farmers are going through a lot of mental stress and anxiety with the drought, and we thank the community for that support,” Simson says.

“But it’s a delicate balance. While we need to show empathy and support for farmers who are going through tough times, that is definitely not every farmer. Most are buckling down and dealing with drought as they always have and the danger is that if farmers are always seen as having their hands out, we risk drawing down our trust bank.”

Statistics on exactly how many farmers are in deep trouble because of the sweeping drought — and who they are and where they live — are hard to quantify.

Federal Agriculture Minister David Littleproud yesterday told Inquirer that 14,000 of the 90,000 family farms (15 per cent) in Australia appear to be eligible for the government’s Farm Household Allowance, a low-income family or personal support payment.

In a $190m special NSW drought initiative announced by Malcolm Turnbull, who owns a farm in the hard-hit upper Hunter Valley, a special additional FHA payment of $12,000 for a couple or $6000 for a single adult was added last week for this financial year to the standard annual support payment of $16,0000.

But it is not known if these eligible farmers (only 8000 of whom have applied for the FHA) are all recently drought-affected farmers suffering from less than a third of their annual rainfall in the past year, or if their low income is because of other factors, such as the ongoing dairy milk price crisis or even deliberate tax minimisation.

When asked who are the NSW farmers finding it hardest to withstand the latest drought, Burrow and Simson point to the so-called 20:80 production curve.

In Australia, according to Australian Bureau of Statistics figures, the most profitable 20 per cent of the nation’s 130,000 farms produce more than 75 per cent of food and rural output by value.

The bottom 50 per cent of farms, in terms of turnover and profitability, presumably the smallest landholders, hobby farmers, lifestylers and older conservative farmers, grow and produce just 12 per cent of the nation’s food and fibre product.

It is this group, which represents more than 12,000 farms in NSW alone, that is least likely to be able to withstand a prolonged, deep drought such as the one the entire state is experiencing.

Simson says: “It is never the same circumstances for everyone and this is not a blame game about good and bad farmers, or big farms versus smaller holdings, but to keep agriculture growing to become a $100 billion industry by 2030 we need to build resilience and these modern skill sets into every farm business.’’

Also forgotten amid all the drought-and-disaster circus focused on NSW is that the other states are soldiering on well.

Western Australia is enjoying a bumper cropping year; Tasmania is still looking green; and while parts of Victoria and South Australia, such as the Eyre Peninsula, are extremely dry, other regions are enjoying an average or even better year.

Even northern Queensland is largely back in business after good summer rains and March floods, although pleas are growing stronger for farmers in southern Queensland around Chinchilla, Dirranbandi, Augathella and Charleville, who have suffered six years of drought not to be ignored in the NSW drought mania.

“It’s not that we don’t support the NSW farmers, but it all seems to have become a media circus and like Queensland is being forgotten,” says Chantel McAlister, a wool classer whose husband’s family had to sell and move off their Meandarra sheep farm west of Dalby last year after drought.

She, her shearer husband and four-month-old baby now live in a caravan and are moving wherever the sheep work is available.

“We feel like we have been in drought for so long up here but we just seem to get on with it and don’t do this pulling-on-the heartstrings thing (like NSW),” says McAlister.

“The idea that you would ever let your sheep get to the point where you have to shoot them is offensive to a Queenslander because we are so used to drought; up here we just destock, pull our heads in and survive.”