John McCain: twilight of a statesman

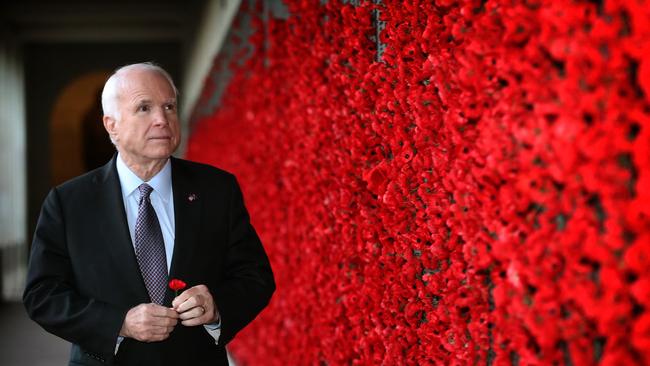

The man who rallied support for Australia in a recent diplomatic storm has been at his blunt best as he battles brain cancer.

Australia’s best friend in Washington is giving a long goodbye to his country and to those he loves. But in dying, as in life, John McCain is doing it in his own maverick way.

As brain cancer slowly overcomes this 81-year-old elder statesman of US politics, McCain is saying his goodbyes while firing some parting shots as he calls for a return to civility in politics in an era of Donald Trump and political populism.

McCain has written a book, his seventh, to be released next week and says he is not even sure he will live long enough to see its release.

In July last year McCain, was diagnosed with the aggressive brain cancer glioblastoma, an illness that claimed the life of fellow senator, Massachusetts Democrat Ted Kennedy. The disease has progressed to the point that the six-time Republican senator from Arizona is considered unlikely to return to Washington and to the Senate chamber, where he has seemed a fixture for as long as anyone can remember.

In his twilight days, McCain is governing from the outdoor deck of his ranch in Sedona, Arizona, dispatching bluntly worded statements and press releases that still have the power to echo across Washington.

The veteran senator has been a fighter pilot, a prisoner of war, a presidential candidate and — despite his colourful clashes with Trump — he commands admiration and respect on both sides of US politics.

As such, a steady stream of America’s rich and powerful are making the pilgrimage to his ranch, not to say goodbye — McCain doesn’t like such sentimentally — but to have one last chance to talk with him while they can.

Says former vice-president and Democrat Joe Biden after spending a day with McCain at his ranch: “John knows he’s in a very, very, very precarious situation, and yet he’s still concerned about the state of the country.” Biden’s son died from glioblastoma in 2015 at the age of 46.

“We talked about how our international reputation is being damaged and we talked about the need for people to stand up and speak out,” says Biden, 75, who is considered likely to run for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2020. “I wanted to let (McCain) know how much I love him and how much he matters to me and how much I admire his integrity and his courage.”

If Biden, who has not confirmed that he will run, was seeking the unlikely imprimatur of the Republican elder statesman to run against the sitting Republican President in Trump, it appears that he received it.

Biden says only that McCain encouraged him to “not walk away” from politics, a hint that McCain thinks Biden should run.

In recent weeks, McCain has taken phone calls from former president George W. Bush, who told him the country was missing him, and had a visit from his closest friend on the hill, Republican Lindsey Graham. The two senators watched the 1962 western The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance and mused about their outsider status as the anti-Trumpers of the Republican Party.

Former New York mayor Michael Bloomberg also dropped in recently, as did McCain’s fellow Republican senator from Arizona Jeff Flake. US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo had planned a visit but that was foiled when McCain was sent to hospital to treat an infection.

McCain has already planned his own funeral. It will be held at Washington’s National Cathedral. After sparring with Trump on and off since 2015, McCain has asked that the President not attend the service.

McCain has written his final book as a long epitaph, in the same way the cancer-stricken Kennedy did when he wrote True Compass in 2009. Kennedy died just before it was published.

In McCain’s book, The Restless Wave: Good Times, Just Causes, Great Fights, and Other Appreciations, he longs for the Republican Party to return to its roots and for the US to take a more assertive leadership role in the world. He calls for a more civil political discourse rather than the fractious and polarised politics of Washington today.

“Before I leave, I’d like to see our politics begin to return to the purposes and practices that distinguish our history from the history of other nations,” McCain writes in his 380-page memoir. “I would like to see us recover our sense that we are more alike than different. We are citizens of a republic made of shared ideals forged in a new world to replace the tribal enmities that tormented the old one.

“Even in times of political turmoil such as these, we share that awesome heritage and the responsibility to embrace it.”

The book amounts to McCain’s final argument for the Republican Party to return to the free-trade, pro-immigration ethos that attracted McCain to it in the first place and that has fallen out of fashion under Trump.

He says congress needs to return to “regular order”, to learn the art of compromise again. McCain recounts in the book how one critic tried to taunt him by labelling him a “champion of compromise”.

“You’re damn right, I’m a champion of compromise in the governance of a country of 325 million opinionated, quarrelsome, vociferous souls,” McCain writes. “There is no other way to govern an open society, or more precisely, to govern it effectively.”

McCain has always been more willing than many of his fellow congressmen to speak bluntly and he says his terrible health diagnosis has liberated him even more in this book. “I’m freer than colleagues who will face the voters again,” he writes. “I can speak my mind without fearing the consequence much. And I can vote my conscience without worry.”

McCain has long had a fractious relationship with Trump and refused to endorse him for president during the 2016 campaign. In 2015 Trump famously attacked McCain, saying the five years McCain spent as a prisoner of war in Vietnam did not make him a war hero: “He’s not a war hero. He’s a war hero because he was captured? I like people who weren’t captured.”

While Trump has been respectful to McCain since his illness, the President has never forgiven McCain for his decisive vote against repeal of the Affordable Care Act, dubbed Obamacare. McCain’s action robbed Trump of one of his signature campaign pledges.

In the book, McCain takes aim at Trump, accusing him of undermining what McCain sees as core American values.

“He seems uninterested in the moral character of world leaders and their regimes,” he writes of the President. “The appearance of toughness or a reality show facsimile of toughness seems to matter more than any of our values. Flattery secures his friendship, criticism his enmity.”

McCain criticises Trump on immigration and on press freedom.

“The way he speaks about (refugees) is appalling, as though welfare to terrorism were the only purposes they could have in coming to our country,” he writes.

On the media, McCain says “his reaction to unflattering news stories, calling them ‘fake news’ whether they’re credible or not, is copied by autocrats who want to discredit and control a free press”.

But McCain, an old-style foreign policy hawk, spends much of his book warning of the threat posed to the US by Russian President Vladimir Putin.

“Putin’s goal isn’t to defeat a candidate or a party,” he writes. “He means to defeat the West.”

McCain reveals that in November 2016 he received a copy of the notorious Steele dossier, which made lurid and unverified allegations involving Trump and Russian prostitutes.

He says he gave the dossier to James Comey, the FBI chief at the time, a move that McCain says has exposed him to allegations that he is an agent of the “deep state” that acted out of jealousy towards Trump.

Not so, he says.

“I had strongly disagreed with candidate Trump’s admiration for Vladimir Putin, which I put down to naivety and a general lack of seriousness about Putin’s antagonism to US interests and values,” he says.

“I was sceptical that Trump or his aides had actively co-operated with Russia’s interference. But even a remote risk that the President of the United States might be vulnerable to Russian extortion had to be investigated.

“I discharged that obligation and I would do it again. Anyone who doesn’t like it can go to hell.”

McCain’s comments in the book clearly have rankled the White House. McCain added to this last week by saying he did not support Trump’s nominee to head the CIA, Gina Haspel, because of her involvement in overseeing controversial integration methods, including the waterboarding of terrorist detainees.

“The methods we must employ to keep our nation safe must be as right and just as the values we aspire to live up to and promote in the world,” said McCain, who was tortured by the Vietcong during his time as a PoW in Vietnam.

“(Haspel’s) refusal to acknowledge torture’s immorality is disqualifying.”

McCain’s stand — which came as Republicans were trying to rally the numbers to approve Haspel’s nomination — was too much for some in the administration.

“It doesn’t matter, he’s dying anyway,” White House aide Kelly Sadler joked at a meeting inside the White House.

When news of that comment leaked, the McCain family was furious.

“May I remind you my husband has a family, seven children and five grandchildren,” McCain’s wife Cindy wrote to Sadler on Twitter. McCain’s daughter Meghan says: “I don’t understand what kind of environment you’re working in where that would be acceptable and then you can come to work the next day and still have a job.”

In his book, McCain admits to making many political mistakes. He says he regrets not picking former senator Joseph Lieberman as his running mate when McCain was running for president against Barack Obama in 2008. Instead, McCain picked the gaffe-prone Alaska governor Sarah Palin in a gamble aimed at shoring up the conservative wing of his own party.

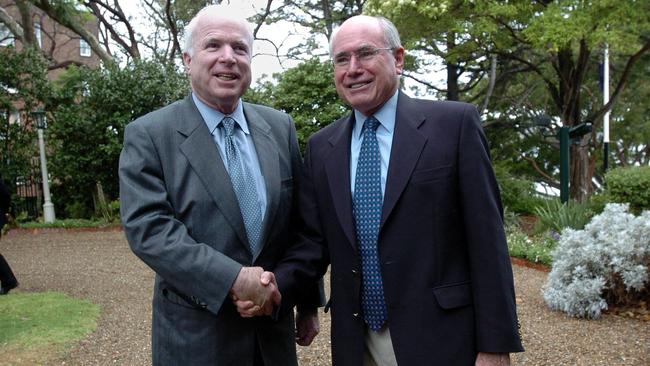

The imminent loss of McCain will rob Australia of its best friend in Washington.

McCain has been warmly disposed to Australia since his father, John “Jack” McCain, told him childhood stories of how he was based in Perth as a submarine commander for the US Navy during World War II.

When Trump argued with Malcolm Turnbull in their fractious phone call in January last year, it was McCain who rallied colleagues on Capitol Hill to make public statements in support of Australia and its US alliance.

“We have fought and sacrificed side-by-side for a long time and it is a unique relationship,” he told The Australian in an interview last year.

While several younger members of congress take a keen interest in Australia and in the alliance, there is no one of the stature of McCain who shares such a personal and powerful connection between the two countries.

But as the sun slowly sets on his life, McCain seems content with his place in history and with the contribution he has made.

“ ‘The world is a fine place and worth the fighting for and I hate very much to leave it’, spoke my hero, Robert Jordan, in For Whom the Bell Tolls,” McCain writes. “And I do, too. I hate to leave it. But I don’t have a complaint. Not one. It’s been quite a ride. I’ve known great passions, seen amazing wonders, fought in a war, and helped make a peace. I made a small place for myself in the story of America and the history of my times.”

Cameron Stewart is also US contributor for Sky News Australia.