Ex-Muslims liberated by lack of faith

Ex-Muslims are the most oppressed people on earth, facing prison and death, so why is the West so wary of giving them a voice?

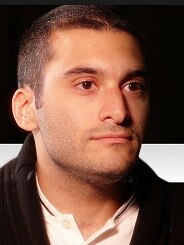

By his own admission Armin Navabi was a particularly anxious child but, still, to hear him talk about his fretful boyhood is to weep for the fear in him.

Navabi, 30, was born in Iran and raised in what he describes as a “fairly liberal family”.

“My parents drank alcohol, they didn’t fast, they only went to the mosque for funerals and weddings,” he says.

“But because of the school I attended, it was much more devout, my teachers were much more devout, and so I became very religious at a very young age, a fundamentalist Muslim at a very young age.

“I want to explain what that was like. You are always ashamed, from age four or five, of what you are thinking, you are always apologising. It is a kind of mental torture, I think, to push religion on to small children, who will believe everything you say.

“There are so many rules and you can’t ever be good enough. You feel so disgusted with your thoughts every day. And you know the punishment. If you sin — and you are always sinning — even in your thought, you will burn forever. And how does it feel, to burn forever? I had to know, so I burned myself, held a fire to my arm, and I could hardly stand it, not for one second, so how will it feel forever?

“It scared me so much.”

Navabi, who will travel to Australia from his new home in Canada next month to talk about the long road to freedom — including in his mind — from his religion, recalls spending many hours hassling friends about their lack of faith.

“All around me, kids are watching Hollywood movies, they are dancing and doing other things, and nobody seemed to care about going to hell,” he says.

“I would ask them: Are you Muslim? Yes. Do you read the Koran? Yes. Aren’t you afraid you are going to punished?

“They would say: I don’t think he (God) cares. I would say, ‘Have you read the book, because it seems like he cares a lot? You should be careful.’ ”

Navabi says the constant misery — nightmarish scenarios dancing all day in his head — ultimately led him to consider suicide, not to escape life but as a way to get to heaven.

“I had this idea come to me,” he says. “In Christianity you are born into sin, but in Islam it’s all about the age of reason. For girls it’s nine, for boys it’s 15 — and whatever you do before that, it’s not sin, you’re still pure, because you haven’t reached the age of reason.

“So I thought, why don’t I commit suicide? It is a sin in Islam, but not before the age of reason, so not if I do it before I’m 15, I’m guaranteed, I’ll just go to heaven.

“So,” he says, before pausing …

“So I jumped out of my window of the school.”

The teen Navabi fractured his back and broke both legs. He was in a wheelchair for seven months.

“And all I wanted was to try again,” he says. “The reason I didn’t try it again: my mother collapsed on the ground with stress, I saw my dad cry for the first time.” He recovered enough to return to school, where he attained marks good enough for Tehran University, but also for the University of British Columbia in Canada, where he now lives.

“I decided to leave because, as I got older, I became more aware of other people, non-Muslim people, in the world around me, and I thought: Europeans, everyone, they are all going to burn forever? Millions and millions of people?

“It didn’t make sense to me, and I started studying the history of religion, and the more you read the more it starts to look like this is all made up, and as an observant Muslim I had never considered that as an option. Do I even dare think it? Am I really so arrogant?

“But then I met other people who were sceptical and, really, by 18 I was fully atheist.”

From his base in Canada, Navabi works passionately for those seeking freedom not of but from all religion.

“I was 21 years old when I went to Vancouver, and I’ve been here 15 years now, but back then I was lonely and I was looking for people who were thinking the same way as me — that it’s all rubbish used to control people,” he says.

He formed an online group, Atheist Republic, which, to his ongoing amazement, is now the largest organised atheist group in the world, at least by online membership. “We have more than two million members, and we have groups here in Canada, in the US, in India, Mexico, Malaysia, in Iran. Truly it’s global and it’s not only ex-Muslims. I’ve met plenty of people who are scarred by their upbringing in different religions.

“But speaking honestly, it really is ex-Muslims who suffer most because ex-Muslims, they are the most oppressed people in the world, because if you think about it, what other minority group is there, in 13 countries the punishment is death just for being, just for having an opinion?

“Christians don’t experience that right now, Jews don’t.

“Truly, ex-Muslims are hated, and we are trying to normalise our lives, trying to get people to get over it: you believe and we don’t, and that’s that, you don’t have to try to kill us.”

Navabi says he will speak at the Melbourne conference about his frustration with Western media, especially its coverage of the bold dash for freedom by Saudi teen Rahaf Mohammed (formerly al-Qunun), who locked herself in a Bangkok hotel room this month rather than return to Saudi Arabia.

“It felt to me that they — Western media — are shying away from mentioning that she has renounced Islam,” he says. “They are focused on the feminist issue, and that is important, because all religion is anti-woman, but let’s be serious: she’s an apostate, that’s the main reason she’s in danger.

“She’s left Islam. She’s an atheist. It’s an act of terror in Saudi Arabia to leave the religion and the West is focused on how she is fighting for women’s rights — and she is, but that is not the main thing.

“I saw some videos of her talking (in Arabic) and in the (English) translation, they were taking out what she was saying about leaving Islam. Even in the West, we don’t want to touch it, but she is not shying away from it. She is trying pork, she’s burning her abaya. She’s so brave, she’s so in-your-face, she’s saying, ‘I didn’t want to pray, I didn’t want to wear the hijab.’ And it’s other people — born and raised in free countries — they are shying away from her position.

“Being ex-Muslim, that’s the big taboo.”

Navabi concedes that he, in his social media activity and on Atheist Republic, also seems quite focused on women’s issues. “They are important, but that is because it is women in Saudi who are most visible when they reject Islam,” he says. “Because of Atheist Republic, people are sending me videos from Iran of women taking off their hijab, and I can translate, and I can verify, I can go on to the Iranian news service and I can see that this is a movement, it is real.

“I have people on the ground and they can confirm it for me, these things are happening, and when women are taking off their hijabs, dancing, driving when they are not allowed to drive, people get excited. They want to see that, and that is something people are comfortable talking about.

“They are not comfortable talking about being ex-Muslim.”

The co-founder of the Society for ExMuslims Australia, Sabeena Mozaffar, 24, who will speak at the same conference as Navabi next month, says she also noticed Western media shying away from Rahaf’s decision to quit Islam.

“I saw so many Muslim scholars tailor a narrative claiming it’s all a Western conspiracy, claiming she is a porn star or even pregnant (while not being married), and so on.

“It is occurrences like these that motivate my activism because I know I can’t stay silent and let them win. I can’t let more people get brainwashed by this falsehood. The case was beneficial in that way. Obviously, it shed light on gender inequality and the mistreatment of women in Saudi. It started up conversations and made Islam a topic of discussion.”

But, she says, the “sloppy journalism and the Left’s unwillingness to publicly criticise Islam” annoyed her.

“I saw multiple news outlets trying to highlight Rahaf’s struggles with issues specific to Saudi Arabia (such as the male guardianship system). They were attempting to differentiate between Islam and an individual country’s controversial laws.

“The fact is that Saudi Arabia’s laws are themselves influenced by Islam, which works as a political theory to govern people.

“Growing up in a Muslim country where any criticism of Islam is equated to blasphemy — a crime punishable by death — I witnessed first-hand how Muslims were unwilling to have their beliefs challenged.”

In Australia Mozaffar has “come across so many Muslims who have a hatred for the West, who believe all media across the globe and education systems are controlled by Israel and that 9/11 was conducted by the Jews; Muslims who believe gays, apostates and other minorities deserve death. On the other side, there is the regressive Left, who blindly equate Islam to peace, love and tolerance. But Muslim-majority countries have laws that are influenced by the Koran and hadith.”

Seven of the eight speakers at Losing My Religion are former Muslims and the event is subtitled Ex-Muslims Speak Out, but attendees also will hear from the founder of the Secular Party of Australia, John Perkins, an atheist who argues that “religious indoctrination” of children in schools is a violation of the rights and interests of the child.

Mozaffar says Muslims who renounce their faith are worthy of special attention because they, more than other atheists, are subjected to a dizzying campaign of vilification, especially online.

The conference Losing My Religion: Ex-Muslims Speak Out takes place at Bayview on the Park, Melbourne, on February 9. Tickets are available online.