Downstream lament: cotton, it’s so absorbent

Growers are using hi-tech instruments to boost efficiency.

Proud Mildura resident and famous River Murray chef Stefano de Pieri has had enough of watching his local farming communities die as their supply of irrigation water dwindles and the Darling River turns into a dust bowl.

But unlike many along the rivers, de Pieri is not blaming the $13 billion Murray-Darling Basin Plan or the Canberra bureaucrats who administer it for the slow shrinking of his beloved river towns and the failure of many of the small battler farms along its banks.

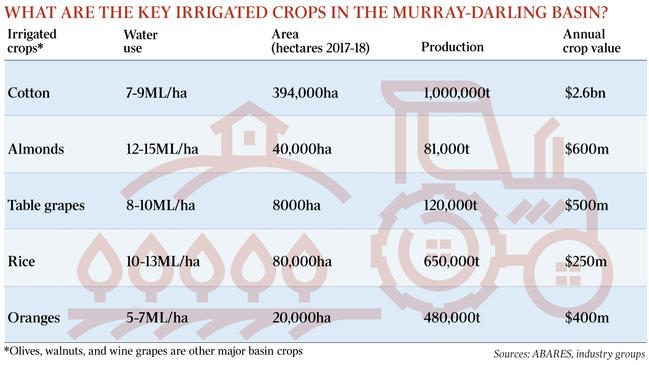

Instead it is the thriving and powerful $2.6bn cotton industry he has in his sights.

De Pieri is at the forefront of mounting calls for a ceiling or planting limits to be put on Australia’s fast-growing irrigated cotton farms, as new varieties of faster-growing cotton allow its tentacles to spread south from its traditional home in northern NSW and southern Queensland deep into the Murray and Murrumbidgee river valleys of southern NSW and northern Victoria.

He says too much cotton is being grown and it is taking so much water in the Murray-Darling basin that other farmers, with less profitable businesses such as dairy farming and wine grape-growing, are being pushed out because they can no longer afford to buy water.

“I’m not against cotton and I am not usually in favour of government restrictions on free enterprise, but this has gone too far; we have to have a cap or limits of the production of cotton in the basin,” de Pieri told a recent Save the Darling protest rally in Wentworth, where the Murray and Darling meet.

“There have to be new controls put on the endless consumption of irrigation water for various types of thirsty crops, particularly cotton, because it is taking too much water and these growers are making too much money.”

He fears cotton growers, many of whom are corporate farming businesses such as Webster, Olam, Auscott and foreign-owned investment funds, are becoming too powerful, leaving little water or voice for smaller irrigation farmers and country towns in the basin.

“When there is no water left for others, there is no wealth, no employment and no opportunity; everywhere down the river from where these cotton farms are — and you only have to look at the whole of the Darling River from Bourke to Wentworth — there is nothing; it’s a very sad picture,” says de Pieri.

“There has got to be a balance between crops like cotton, the river and the communities; I know cotton growers say that because the whole system has limits on it and water is traded everything should be OK, but that’s not what I’m seeing at the moment.”

But calls for government controls on any productive agricultural, including cotton, make farmers see red.

They say that what is little understood by city slickers and greenies obsessed by the cotton industry is that few of them grow just one commodity on their properties; that most annually planted crops such as cotton, rice, chickpeas or wheat are planted in a rotation to keep soil fertility high, to reduce weeds and to prevent monocultures.

Nor is cotton the thirstiest commodity grown in the basin. Per hectare of land, nut trees such as almonds and walnuts use much more water than cotton, yet vast new almond groves are proliferating along both sides of the Murray River from Victoria’s Swan Hill to South Australia’s Riverland.

Cotton Australia chief executive Adam Kay says Australian cotton growers are the most water efficient in the world.

Water consumption of cotton crops has been nearly halved with the introduction of technology such as laser-levelled paddocks, moisture sensors, satellite measurement of crop biomass growth rates and less thirsty cotton varieties.

At the same time, yields of cotton lint harvested per hectare have jumped, delivering a boost to the amount of cotton produced for every drop of water used, which in Australia is three times higher than the world average.

Sunny Verghese, global head of international trading giant Olam — which owns Queensland Cotton and is one of the biggest cotton growers and processors in the world — was effusive in his praise for the sophistication of the Australian cotton industry in a recent address to The Australian’s Global Food Forum.

He says while Australian farmers are high-cost producers of cotton per tonne, they are also the most profitable because the cotton is high quality; the yields are the best in the world at 12 to 15 large bales a hectare; and water use has been cut through innovation by more than 40 per cent in the past decade to be the lowest among irrigated cotton-growing nations.

Verghese says Olam’s priority has been to reduce risk through the adoption of cutting-edge technology to make its irrigated cotton and Murray River almond farms more sustainable and water-efficient.

“Water is a scarce resource; all farmers have a responsibility to use it as efficiently as possible, not just for their own financial benefit but for environmental and social obligations too,” Verghese says.

“But using less water doesn’t mean less production or profitability. Technology is helping us in so many ways be so much more efficient water users.”

At Olam’s 15,000ha of almond orchards in Australia, internet of things sensors called dendrometers are being installed on every tree to measure tiny changes in the expansion and contraction of the trunk, which then sends a signal to the drip irrigation system to release the exact amount of water each tree needs.

The technology is expensive, but it has allowed Olam to cut its water use per hectare of almond trees by nearly 20 per cent from 15 megalitres to 12.5ML/ha. With permanent water rights costing $4000/ML and annual water costing about $250/ML, Verghese says “it’s a big deal”.

But such talk of the cotton industry being so highly water efficient and environmentally advanced rings hollow or at best has little impact to the thousands of Australians scandalised last year by allegations of deliberate water theft by several big growers on the Barwon-Darling River system in southern Queensland and northern NSW between Walgett and Bourke.

Some farmers were accused of deliberately disabling water pump measuring meters or taking water at forbidden times, and others faced allegations of building illegal dams and levee banks to push more river water flowchart on to their properties.

Four families are being prosecuted in the NSW Land and Environment Court.

One fellow farmer appalled at the revelations by the ABC’s Four Corners program was outspoken Menindee grazier Rob McBride, who already was blaming greedy cotton growers upstream of his Tolarno Station on the Darling River of overextraction.

“Now I think it’s much worse than that; cotton is destroying our rivers and its growers have single-handedly broken the integrity of the Murray-Darling Basin Plan,” McBride says.

“They have also destroyed the trust the public and most farmers had that the plan was fair and that environmental water was ending up being used as intended.

“In my view, the cotton industry has lost its social licence to operate.”

Big Moree cotton grower and Gwydir Valley Irrigators Association chairman Joe Robinson, not surprisingly, disagrees.

“Everybody says bloody cotton growers but nobody here supports water theft or taking environmental water when it has been embargoed (by the government); the old days of getting water whatever way you can are gone,” Robinson says. “But those allegations have done huge damage to our integrity.

“It is unfortunate because most people are doing the right thing and this industry is so hugely important; it underpins the economy of towns like Moree and Collarenebri and we have already given up 20 per cent of our water here to make the plan work.”

Moree agronomist Tim Poole makes his living working with cotton and wheat growers, and he says awareness is growing of the need to listen to the wider community if calls such as de Pieri’s for the scale of the cotton industry to be reined in don’t gain further ground.

“I find it difficult when you are in the industry, have a scientific background and know how good cotton is for the community and the economy, to see cotton getting such a bad rap and then having to argue back on emotive issues,” Poole says.

“It sometimes feels almost like a religious fervour — alongside things like all chemicals are bad and gluten is killing everyone — yet the reality is that there are so many exciting developments that the cotton industry is at the forefront of, like robotics, optical weed sprayer and new irrigation technology, that it is just getting better, more advanced and more efficient all the time.”