Trump stands to lose the shutdown power play

The US President's preference to always be the star of his own show is leaving him exposed.

Donald Trump loves power but he understands fame. In the government shutdown impasse he has confused the two and lost some power as a result. This is uncharacteristic. Normally Trump uses fame to accumulate power. But not this time.

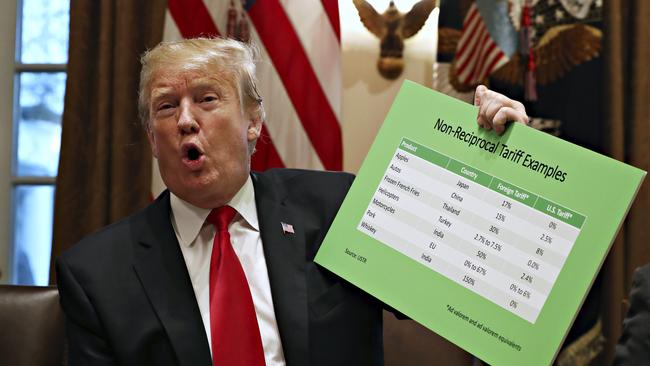

In most situations, he understands the dynamics of power. He is brutal in using US power internationally. Ask the Chinese.

Most of the results he has achieved internationally have not involved the deployment of military force, though that threat is often there.

But in domestic politics a president has much less power to act unilaterally. He is tripped up everywhere by the checks and balances the framers of the US constitution put in place to curb strong-willed presidents.

Trump is losing the power fight to Nancy Pelosi and the congressional Democrats. He is even losing the symbolism. Pelosi told him, as Speaker, she wouldn’t allow the House of Representatives to host a State of the Union address while the government was in shutdown. At first Trump slammed Pelosi and declared he’d give the address somewhere else. A few hours later, realising the pomp and circumstance of a traditional State of the Union are visible signs of presidential status and he couldn’t afford to squander them, Trump backed down, saying he would make the speech after the shutdown was finished, just as Pelosi had demanded.

The whole government shutdown is a shameful business that reflects badly on both sides of US politics. It comes when the strategic credibility of the administration is being called into question much more intensely.

It is a dismal case of the overriding need for all US political leaders to stir up their respective bases, to define above all what and who they are against and to reject compromise as weakness.

On the campaign trail Trump promised to build a wall on the border with Mexico. He wants $US5.7 billion ($8bn) to do it. The Democrats, who funded hundreds of kilometres of wall under Barack Obama, now claim with extreme hypocrisy that such a wall is immoral and they won’t fund it.

Most Americans want secure borders. They want control over immigration and greatly reduced illegal immigration. A wall would help in that, just as Obama’s partial wall has led to a slowdown in illegal immigrants.

But Trump is badly losing the politics of this confrontation. Polls go back and forth over whether Americans want the wall or not. But they are absolutely clear that they do not want the government shut down. When Trump addressed the nation early on in the shutdown, he spoke about illegal immigration and the wall. The Democrats’ response, delivered by Pelosi and Senate minority leader Chuck Schumer in funereal downbeat monotone, talked about the shutdown.

An NBC poll shows 70 per cent of Americans don’t think the wall is worth shutting the government down. American polls can be misleading. Those who write about Trump — and I have sometimes been guilty of this myself — tend to focus on the outlier polls that show big swings of support or opposition. On any day there is a poll somewhere that demonstrates that Trump is a genius or a loser. Take your pick.

That is why the RealClearPolitics average of polls is such a useful tool. It has its own limitations and it is a lagging indicator because some of its polls are older than others. But it is a rolling average, routinely updated and without political bias. It has often shown Trump’s figures rising when conventional wisdom held that he had performed badly.

Until the government shutdown, Trump’s approval rating had been remarkably stable, generally ranging from 43 to 45 per cent. You can argue that it is a low rating for a president overseeing such a good economy or that it’s a high rating given the ferocity and relentlessness of the attacks on Trump.

Given the relatively narrow and specific base of Trump’s electoral win in 2016, and the relatively narrow base of his re-election bid, leaving giant states such as California and New York, indeed much of the two coasts, uncontested, an overall approval rating of 45 per cent means Trump is well positioned to be at least extremely competitive in 2020.

But in the month of the government shutdown, Trump’s net approval rating, according to RealClearPolitics, has fallen by five percentage points. His approval rating is down to 40 per cent and his disapproval rating, which helps predict the intensity of folks who will vote against him, is up.

In other words, almost uniquely, Trump in this controversy is starting to lose some of his base over this issue.

Whenever that situation has threatened before, Trump has been quick to change. He normally disguises a policy reverse by declaring victory and producing a big diversion on some other issue.

One consolation for Trump is that support lost during a government shutdown has been only temporary in the past, but a sustained approval rating below 40 per cent would be very challenging for Trump. It might further destabilise the world, just incidentally, because Trump would face an enormous temptation to act dramatically in an international dispute to polarise sentiment behind him.

By the end of the week, Trump was nearly suing for peace and looking for a semi-honourable surrender. He proposed to fund the government and give the Democrats serious concessions on other elements of immigration policy if he got even a down payment on his wall, even a few hundred million dollars.

But each side of US politics now conceives of the other side as inherently evil. Nobody can afford to compromise. Nobody wants to compromise. The Democrat leadership is at least as cynical as Trump. It would gladly fund the wall under Obama but must not give one dollar to Trump for the same purpose.

Republican senators were starting to peel away from Trump. Several at week’s end voted for a Democrat bill that would have reopened the government without providing money for the wall.

Increasingly, Trump’s people were canvassing the idea of his declaring a state of emergency on the southern border. This would allow him to take money from other government departments — notably Treasury and the Pentagon — that had already been approved for other purposes and use it for the wall.

In a sense the move is ridiculous as there is certainly no emergency. But it is a manoeuvre other presidents have used in different ways. It inevitably would be challenged in the courts, but there is now a conservative majority on the Supreme Court that is sympathetic to the substance of presidential prerogatives.

Immigration reform is a filthy issue in US politics. Both Republican and Democrat use it cynically to mobilise their respective bases. Because voter turnout is all important, the issue works for both sides of politics even when the policies of one side are more favoured by the electorate.

Democrats wilfully use the issue to paint Republicans not only as heartless but also as racist, in the hope especially of securing the permanent disaffection for Republicans by the growing Hispanic minority, in the way African-Americans vote overwhelmingly against Republicans.

For their part, Republicans, especially Trump, also use the issue cynically, frequently misrepresenting facts and dialling up emotion and rhetoric to dangerous levels.

Optional voting and social media are a toxic interaction in the US. Political success increasingly relies on arousing an intensity of feeling among supporters, not on winning a rational debate.

Trump himself has eschewed compromise on his border wall during the past two years. Republicans controlled both houses of congress until recently, yet Trump never secured his wall and never threatened to shut down government because of this.

It’s true that to get money for the wall authorised by the Senate he needed 60 votes and he never had 60 votes. But there were times when he could have got part of the wall and he walked away from compromise. Both sides of politics want the issue to fester in order to mobilise their voters and donors. It is democratic politics at something near its worst.

Modern populism requires enemies, above all. The American Left has been sliding into its own cesspool of toxic populism — identity politics, anti-Christian activism, hatred of police, falsely accusing countless figures of racism when racism is a real problem but not everyone who is not a liberal is a racist.

All of this called forth Trump. Nothing was better for Trump than Hillary Clinton calling his voters “deplorables”. Tens of millions of Americans self-identified as deplorables in Clinton’s terms and, while they didn’t like everything about Trump, they thought at least he was a fighter.

But for the most part Trump has not shaped these sentiments into a coherent, much less uniting, program of government, even though he has done several specific good things — building up the military, cutting taxes, calling out Beijing for its trade and other destructive policies.

The old saw has it that you campaign in poetry but govern in prose. A modern version might have been that you campaign in anger but govern in forgiveness. Trump, on the other hand, never stops campaigning. Fame itself, even more than power, is his central operating system. His fame grows with his anger. So Trump campaigns in anger and governs in fury.

The news and political cycles seem hyper-accelerated under Trump. Two years into his first term in office it’s as though we are embarking on his second term.

In some ways in national security Trump’s first two years have followed a similar arc to Obama’s first presidential term, their acute ideological differences notwithstanding. Initially Obama was scared of national security, didn’t want to wage political war on his own generals. So he appointed genuine big beasts — Robert Gates (who had served in George W. Bush’s cabinet) as defence secretary and Clinton as secretary of state. Remember, at that point Clinton was a national security hawk, always imagining she would be attacked for softness on national security in a presidential campaign.

Therefore, while Obama’s first term had its problems, it ran more or less along conventional US foreign policy lines. By the time of his second term, Obama was liberated to be himself. He appointed extremely weak defence secretaries and a left-liberal of no consequence, John Kerry, as secretary of state. The real Obama — isolationist, obsessed with virtue signalling on zeitgeist issues and well to the left of his nation — emerged.

Trump has done something similar. In Jim Mattis as defence secretary, US allies and much of the world found reassurance. Now Mattis is gone and his all but anonymous acting replacement has no strategic background. The White House chief of staff and attorney-general are only acting positions. All the generals who gave Trump’s first two years whatever sense of competence and continuity it possessed are now gone. So, too, is Nikki Haley.

Trump, virtually now in his second term, is happy to surround himself with non-entities. In Trump’s universe of fame, there is room for only one star. But the realities of power require a president to have allies, domestically and internationally, and to listen to them.

A US government partly shut down, and that has so lost cross-party comity that it cannot even hold the State of the Union address, is starting to cut into its strategic credibility. That’s bad for everyone.