Divisions open over powers and make-up of commonwealth ICAC

The powers and make-up of a national integrity commission are proving divisive in political and legal circles.

Last weekend, as the push for a federal ICAC was reaching fever pitch, the former judge who spent years running the nation’s oldest anti-corruption agency let the cat out of the bag.

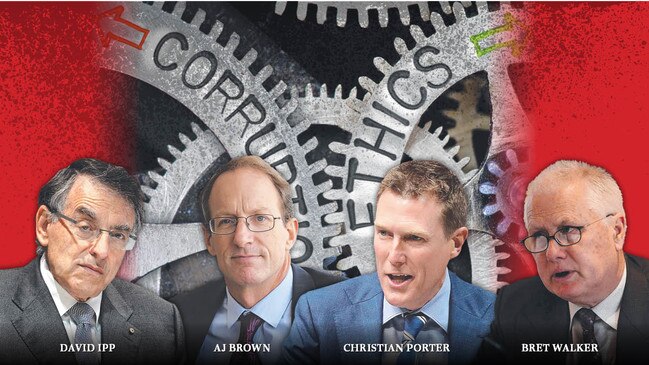

David Ipp, the former boss of the NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption, was asked on ABC’s Radio National how to resolve any turf wars between the existing federal integrity agencies and the proposed new commission.

It was a good point. The exact number of integrity agencies keeping an eye on the federal public sector is a live issue. Estimates range from a mere 13 all the way through to 27.

When the ABC’s Cathy Van Extel was talking to Ipp, she settled on 21 and wanted to know how he would resolve the overlapping jurisdictions if a powerful new body were added to the mix.

Ipp was ready. After stepping down from ICAC in NSW, he has been helping the Australia Institute promote a vision of what a federal ICAC would look like.

After Van Extel asked if the jurisdiction of the integrity agencies “would all be muddled in”, he conceded that “it could be if it is not handled properly”. But it was what followed that appears to have startled the ABC’s presenter: “One way is simply to abolish all 21 and have one umbrella body,” Ipp said.

Van Extel, while suppressing laughter, then asked: “We are not going to get rid of the AFP, are we?”

Ipp pressed on, criticising the Australian Federal Police for “only investigating criminal matters” while “many corruption matters are not criminal”. He did not back away from the idea of doing away with the AFP and 20 other agencies as part of the switch to an all-powerful commission.

It later became clear that this was no laughing matter. Deep inside independent member for Indi Cathy McGowan’s bill to create a national integrity commission are provisions that would allow the agency to sidestep the careful division of responsibilities that are a feature of the justice system and discard key procedural safeguards that protect the rigour of the courts and the rights of the individual.

This commission could even establish its own police force that would be less accountable than the AFP. It would have the power to arrest people, investigate their conduct, force them to disclose documents, array them before public hearings and declare them corrupt. McGowan’s explanatory memorandum says these findings would be subject to judicial review. But, as lawyers know, that means a restricted form of appeal that is limited to errors of law, not facts.

McGowan’s scheme also talks about “due process” but there would be no privilege against self-incrimination, defence counsel would need permission to cross-examine witnesses on approved subjects, and legal professional privilege would be abrogated by default unless it receives prior approval.

The McGowan bill is based on an options paper produced by Griffith University and Transparency International. And that options paper says the agency would have more than 400 full-time staff and would cost taxpayers almost $94 million a year — and that takes account of savings from the incorporation of the Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity.

This needs to be viewed in context. Details provided by the office of Attorney-General Christian Porter show that the federal government already spends more than $3 billion a year on integrity agencies. This figure is based on estimated expenditure for the present financial year. And it only covers the top 10 (see above).

As this debate has unfolded, Porter has been arguing that the commonwealth already has 13 integrity agencies. But he might have underplayed his hand.

His own department’s submission to a 2016 Senate inquiry listed 10 “key” agencies that were promoting a culture of integrity and 16 others that were playing a role. However, that submission predated the establishment of the Independent Parliamentary Expenses Authority. So if IPEA is added to the department’s 2016 tally, the nation already has 27 integrity agencies costing more than $3bn and is being asked by Labor and the Greens to spend another $94m.

“There is already a very significant amount of money being applied to a variety of agencies where the larger part of that is devoted to integrity and corruption detection, litigation and prosecution,” Porter says.

But he did not rule out funding increases and improving the current arrangements by merging some agencies. Three broad options are being considered and one of them is to have better co-operation or “something that looks like a merger between existing agencies”.

“There are a lot of agencies. There are overlaps in jurisdiction. There can sometimes be a lack of clarity between agencies as to who should be considering a particular matter or type of matter,” Porter says. “So there is definitely room to have greater levels of clarity driven into the system.”

Porter says those who refer to the need for a stand-alone federal integrity agency “show a misunderstanding of the context and the existing landscape”.

“Any new arrangement or body or entity is going to have to work with all of the existing agencies.”

He has dismissed the McGowan bill as unworkable but it has provided an insight into the scale of upheaval that might be triggered by the creation of a federal ICAC.

The plan to establish an elite new police force is outlined in clause 144 of the McGowan bill, which would give authorised officers of the new commission all the powers of a constable under the Crimes Act — including the power of arrest.

Clause 145 means members of the AFP, with agreement from the AFP commissioner, could be co-opted to the new force and given instructions by the national integrity commissioner.

Unlike the AFP, the federal ICAC’s police would not be answerable to the minister for home affairs. They would answer to the commissioner of the federal ICAC, who would bypass ministerial control.

Instead, the commissioner would report to parliament using a mechanism that seems to copy the limited oversight that applies to ICAC in NSW. The commissioner would answer to an inspector and to a parliamentary committee.

This mechanism will be familiar to anyone who watched former NSW ICAC commissioner Megan Latham fend off questions before the NSW parliament’s ICAC oversight committee.

Griffith University’s AJ Brown, who helped design the McGowan bill, says the policing power would be inherited from the Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity, which would be merged with the new commission.

Brown, who was McGowan’s main adviser on the bill, says it is welcome news that the government is working on its own concrete proposal.

But he believes Porter’s response to the bill has been “factually inaccurate” in some key aspects. He says it had been an “extreme form of exaggeration” to assert that public-sector journalists could fall foul of the agency for political reportage that lacks balance. This could easily be clarified, if necessary, in the text of any definition of corruption, Brown says.

If McGowan’s scheme is out, what sort of power should be vested in a federal ICAC?

Bret Walker SC, a former president of the Law Council of Australia, has serious concerns about allowing these commissions to make findings of corruption before anything has been decided in court. He spelled out those concerns in June when he was delivering this year’s Whitlam Oration at Western Sydney University.

“A critical safeguard on the kind of information that an ICAC should be able to give us, in cases of unfavourable findings, is that we should no longer be told that an individual has engaged in corrupt conduct, let alone that he or she has been found to have done so because their conduct involved the commission of a criminal offence,’’ Walker said. “That would be a very serious kind of misinformation, in a society still attached, I think, to the notion of a fair trial before conviction.’’

The incoming president of the Law Council, Arthur Moses SC, has similar concerns that he spelled out two weeks ago at a conference in Sydney of the Australian Bar Association and the NSW Bar Association.

“At a time when state watchdogs like the NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption are under fire for subjecting those under investigation and witnesses to ‘trials’ by media, would a federal ICAC be anything more than an expensive witch-hunt?” Moses asked.

The way forward might eventually draw on some of the thinking of Adam Graycar, who had some mild differences of opinion with Ipp on Van Extel’s radio show at the weekend.

Graycar is a professor of public policy at Flinders University and is a former dean of the school of criminal justice at Rutgers University in New Jersey. He is also a co-author, with Brown, of the options paper that forms the basis for the McGowan bill.

But if the government is keen to save itself $94m a year and avoid a bureaucratic turf war, Graycar’s original position, which was opposed to creating a federal integrity agency, might be worth revisiting.

This is what he told that 2016 Senate inquiry: “There is a loud clamour for a commonwealth ICAC, but why would you want to set one up when you don’t really know what the problem is, when it would certainly be under-resourced, and when any activity would start a massive turf war between overlapping enforcement agencies?

“What I am proposing is the establishment not of an executive agency, but of an anti-corruption council … for discussion and co-operation, and not for the investigation and consideration of individual cases. If cases are brought to the attention of the council, they would be referred to the most suitable agencies.”

-

$3 BILLION OF PROTECTION

The top 10 integrity agencies and how much they cost.

Australian Federal Police

$1,701,933,000

Investigates serious or complex corruption against the commonwealth and plays a key role in corruption prevention and disruption. Hosts the Fraud and Anti-Corruption Centre.

Australian Securities and Investments Commission

$527,528,000

Investigates breaches of the Corporations Act and takes criminal, civil and administrative action in cases of corporate misconduct. Hosts the Office of the Whistleblower.

Australian Electoral Commission

$502,540,000

Oversees and investigates breaches of the financial disclosure requirements under the Commonwealth Electoral Act applicable to political parties and associated entities.

Australian National Audit Office

$114,729,000

Provides parliament with independent assurance about public-sector financial reporting, administration and accountability. Has extensive powers of access to documents and information.

Independent Parliamentary Expenses Authority

$76,820,000

Advises parliamentarians and their staff about travel expenses and travel allowances, and monitors and audits this expenditure.

Australian Public Service Commission

$60,770,000

Promotes high standards of integrity and conduct in the APS and imposes those obligations on employees. Its agency heads deal with misconduct in their agencies; the APS commissioner deals with alleged misconduct by agency heads.

Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security

$28,862,000

Reviews intelligence agencies to ensure they act legally, with propriety, within ministerial guidelines and directives, respect human rights and have effective procedures; has access to a range of coercive powers.

Commonwealth Ombudsman

$50,518,000

May investigate complaints from people who believe they have been treated unfairly by federal government departments or agencies and some private-sector organisations. Oversees the act under which public officials can disclose suspected wrongdoing in the public sector and oversees about 20 law-enforcement agencies.

Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity

$19,540,000

Assists the integrity commissioner to assure government of the integrity of prescribed law-enforcement agencies and their staff, by detecting and investigating corruption. Agencies within its jurisdiction include the:

● Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission

● Australian Federal Police

● Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre

● Department of Home Affairs (including the Australian Border Force).

Those agency heads must notify the integrity commissioner of corruption issues that arise in their agencies.

Inspector-General of Taxation

$12,563,000

Provides independent advice to government on the administration of taxation laws and investigates complaints by taxpayers, tax practitioners and other entities about the administration of such laws.