Day of destiny dawns for the First Fleet

PART 4: After a hellish, storm-tossed voyage, Arthur Phillip brings his ships into Botany Bay.

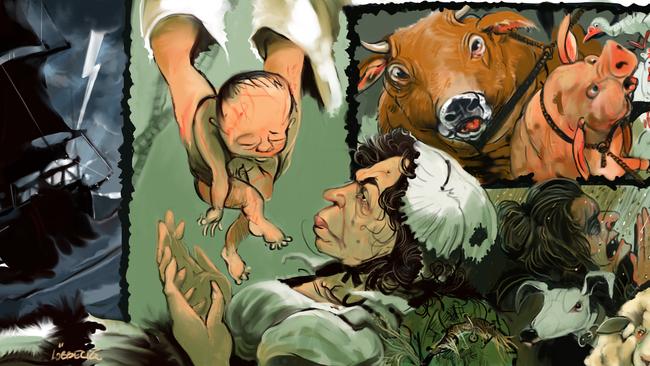

The vicious squall hits two days out of Rio de Janeiro and two days before Mary Braund gives birth. “A very violent storm of thunder and lightning,” writes surgeon Arthur Bowes Smyth. Water rushes through portholes and the 11 ships of Arthur Phillip’s First Fleet pitch and roll as “everything that was moveable” tumbles in kind, including a heavily pregnant Mary Braund, sucking deep for enough air for two in the crowded prison deck of the transport ship, Charlotte. Few places, she considers for a moment, could be more inappropriate for childbirth than a convict transport ship cutting back across the Atlantic Ocean through a tempest in the direction of southern Africa en route to a new home in a prisoner island called New Holland.

Six months from now, on February 10, 1788, Mary Braund will become Mary Bryant when she marries fellow convict William Bryant in the settlement of Sydney Cove. William will acquire a hut for his new family. He’s a skilled fisherman and he’ll be given a good job in the settlement as one of the key operators of the colony’s fishing boats.

In October 1790, a Dutch captain will land at Port Jackson in search of supplies. From this captain, William Bryant will obtain a chart, compass, quadrant and enough stashed supplies of his own to make a daring escape from Sydney Cove. On March 28, 1791, the Bryants and seven other convicts will slip away from the settlement in Arthur Phillip’s stolen six-oared cutter. In an impossible journey that will last 66 days and cross 5000km through the uncharted Great Barrier Reef and Torres Strait, the Bryants will reach the island of Timor where they will claim to be shipwreck survivors. By Mary’s side in that moment will stand the three-year-old girl who is about to enter the world down here in the bilge-foul bowels of a storm-ravaged First Fleet transport.

In the crashing thunder, the “floating farmyard”, the “Noah’s ark” that is the First Fleet echoes with the barks and squawks and howls of the animals tied down across the fleet ships, including Commander Phillip’s greyhounds and horse and Reverend Richard Johnson’s timorous kittens.

In the three storage ships, Golden Grove, Fishburn and Borrowdale, vital supplies collected from Rio de Janeiro roll across tilted floorboards. Plants and seeds destined to change the landscape of New Holland. Coffee plants, orange trees, cocoa, cotton, guava, prickly pear trees.

“Secure the rum!” holler sailors and marines alike. In Rio, the fleet bought 65,000 litres of rum for the remainder of the voyage and for the first three years of the colony.

In the prison decks, the rolling storm-ravaged ships have caused violent outbreaks of seasickness and the convicts must sit in their own inevitable bile and vomit. Breathing is a luxury down here with all hatches battened down to stop water flooding the cells.

On the deck of the Sirius, hard rain and ocean spray slam against the face of American seaman Jacob Nagle and it feels good to be alive. Only days ago he almost had his head split open by a sword after picking up a prostitute in a bar in Rio de Janeiro.

“One evening two of us got into a grog shop,” Nagle writes. “And a very handsome young woman, who was very familiar with me, asked me home with her. I accepted and was on the road as far as one square (when a local man) pushed me away from her. I would not let go my hold and he drew back and drew his sword and was raising his sword over his head to cut me over the head.

“At that instant a soldier turned the corner, drew his sword and guarded the blow he was going to make. Another soldier behind him abused him for meddling with me but the fellow begged their pardons and said I had taken his wife from him therefore the soldier let him go and we went to a grog shop and I treated them for saving my life.

“In the morning, (Second Lieutenant Philip Gidley King) came on shore and took me on board with him and enquired of Governor Phillip what to do with me. He was glad to hear that I was alive and desired them to send me to my hammock to sleep as I would be wanted in the boat at nine o’clock.”

The wild weather carries through the month of September. On the 19th, a convict is tossed overboard the Charlotte.

“William Brown, a very well behaved convict, in bringing some clothing from the bowsprit end where he hung them out to dry, fell overboard,” writes chief surgeon John White.

Later on the Friendship, Captain James Meredith’s untethered dog, Shot, follows William Brown into the drink. Meanwhile, on the same vessel, Lieutenant Ralph Clark is dismayed to discover children — soon-to-be Australians — are being conceived on his ship.

“Two of the convict women that went through the bulkhead to the seamen on 3 July last have informed the doctor that they are with child,” he writes. “I hope the commodore will make the two seamen that are the fathers of the children marry them and make them stay at Botany Bay.”

Deep into the South Atlantic, the fleet flagship Sirius is struggling so much in the prevailing storms its commanding officers wonder if the vessel has the strength to make it to the Cape of Good Hope, much less to Botany Bay. Lieutenant Philip Gidley King writes of “the extreme negligence of the Dock Yard officers in not giving the Sirius the inspection they certainly ought to have done”. But the fleet is well past the point of no return. Their fate is in the hands of Neptune, and a former spy named Arthur Phillip.

In early October, Phillip faces a threat not from the clouds above but the dark prison pits below the transport Alexander. John Powers had a taste of freedom when he slid down the side of Alexander undetected in the Canary Islands. He made it to land in a row boat but could not climb the jagged cliff face that eventually ended his bid for freedom. He was lashed mercilessly for his efforts. Powers has managed to convince a number of sailors aboard Alexander to equip him and a group of like-minded convicts with iron bars.

Upon arrival in the Cape of Good Hope, on Powers’ signal, the group will pounce upon their gaolers and take control of the largest convict ship with brute force and nothing-to-lose audacity. But, not for the first time, the First Fleet mutineers are betrayed by one of their own kind. No honour among starving thieves, especially those looking for special treatment from marines who look kindly on plot betrayers. Powers is promptly ordered on to the flagship Sirius and chained to the deck.

Four seamen charged with assisting the mutiny are brutally flogged. The convict rat in the house is moved to the transport ship Scarborough for his own safety but that measure won’t keep him safe from Powers once they’ve crossed the shores of Botany Bay.

On October 13, the battered fleet anchors in Table Bay, Cape Town, a grim and dangerous Dutch-run colony best defined by the shoreline that greets its visitors.

“There are many gallows and other implements of punishment erected along shore and in the front of the town,” writes surgeon Arthur Bowes Smyth. “There were also wheels for breaking felons upon, several of which were at this time occupied by the mangled bodies of the unhappy wretches who suffer’d upon them: their right hands were cut off and fixed by a large nail to the side of the wheel, the wheel itself elevated upon a post about nine or 10 feet high, upon which the body lies to perish.”

Elsewhere are signs of misbehaving slaves being impaled on poles. In one section of town lay the severed limbs of a Malay slave who had recently lost his mind and ran wildly through town with a machete.

Here, Arthur Phillip is greeted with little of the hospitality he enjoyed in South America. The town’s Dutch governor is reluctant with provisions, forcing Phillip to make repeated applications for food and livestock. Dutch merchants charge the English — who have counted on last-stop Cape Town supplies to carry the fleet through construction of the colony in New Holland — double and triple standard livestock prices.

Surgeon John White observes the courtship rituals of Cape Town women.

“If you wish to be a favourite with the fair, as the custom is, you must in your own defence, grapple the lady, and paw her in a manner that does not partake in the least of gentleness,” he writes. “Such a rough and uncouth conduct, together with a kiss ravished now and then in the most public manner and situations, is not only pleasing to the fair one, but even to her parents.”

During the long wait for supply approval, marines, sailors and convicts still bound to the fleet ships grow impatient. The flame of a brawl between marines aboard the transport Scarborough will flicker all the way to Sydney where one of the brawlers, Thomas Bullimore, will be reportedly murdered by fellow marines. Bloody fist fights remain a regular part of life for convicts beneath Alexander. Sexual assaults less so, especially since Phillip has conveyed his punishment plans for anyone who would commit crimes of sodomy and murder.

“For either of these crimes I would wish to confine the criminal until an opportunity offered of delivering him to the natives of New Zealand, and let them eat him,” he writes. “The dread of this will operate much stronger than the fear of death.”

One night on the deck of the anchored Friendship, a drunk second mate, Patrick Vallance, falls overboard and drowns while trying to relieve himself over the front of the ship.

Shortly before Phillip gives his signal to weigh anchor and sail from Table Bay, officer Watkin Tench, aboard Charlotte, meets the captain of an arriving ship with American colours, bound from Boston. This Boston captain may be the first man to foretell the 200 years of immigration that will forge the multicultural Australia of the 21st century.

“The master, who appeared to be a man of some information, on being told the destination of our fleet, gave it as his opinion that if a reception could be secured emigrations would take place to New South Wales, not only from the old continent, but the new one, where the spirit of adventure and thirst for novelty were excessive,” Tench writes.

On land, Arthur Phillip casts one last eye over the Cape Town landscape and learns a lesson that will serve him well in Australia about “maintaining an establishment in a soil so burnt by the sun and so little disposed to repay the toil of the cultivator”.

“The example and success of this people may serve, however, as a useful instruction to all who in great undertakings are deterred by trifling obstacles,” he writes. “And who, rather than contend with difficulties, are inclined to relinquish the most evident advantages.”

Advantages or not found in Cape Town, he’s relieved to set sail on November 12, 1787.

“In the course of a month, the livestock and other provisions were procured,” he writes. “And the ships, having on board not less than five hundred animals of different kinds, but chiefly poultry, put on an appearance which naturally enough excited the idea of Noah’s ark.”

There are goats, cows and horses, turkeys and geese, ducks, dogs, chickens and pigeons. Women convicts and children occupying living space on board Friendship are forced to make way for an intake of valuable and life-sustaining sheep.

‘We were leaving the world behind us, to enter on a state unknown’

After a long journey across the Southern Ocean — deeply traumatic and difficult for the larger animals — some of the cows on board will escape their confines at Sydney Cove after a storm rips through the settlement. The loss of these cows will help bring the colony to the edge of starvation.

The freed and roaming cows will be seen months, even years, later luxuriating in the verdant hills 70km southwest of the colony in the Menangle-Camden area of Sydney.

They’re 6000 nautical miles from Botany Bay and the distance from home, from wives and sons and daughters, from civilisation, weighs heavily on the fleet.

“The land behind us was the abode of a civilised people,” writes the new colony’s judge advocate David Collins. “That before us was the residence of savages. When, if ever, we might again enjoy the commerce of the world, was doubtful and uncertain … All communications with families and friends now cut off, we were leaving the world behind us, to enter on a state unknown.”

Crossing the vast and dark Southern Ocean, Arthur Phillip splits the fleet, sending the fastest sailing ships onward to Botany Bay, equipped with woodworkers and labourers to make a start on constructing the penal colony before the arrival of the rear half of the fleet. Phillip transfers to the ship Supply, which will lead the three fastest transport ships, Alexander, Scarborough and Friendship, ahead on to NSW.

Mary Braund remains in the rear group with her newborn baby girl, Charlotte, named after the grimy, diseased prison ship in which she was born.

Charlotte rests in Mary’s arms and it’s in these arms that she will die almost five years from now. Having made their historic and impossible odyssey across Torres Strait, the escaped Bryant family will be captured after William Bryant reportedly drunkenly brags of his miraculous travels. Charlotte will die of fever in May 1792, while being escorted by Royal Marines back to England with her mother on board HMS Gorgon.

Mary looks down into the eyes of her child.

“Merry Christmas, Charlotte,” she says.

It’s December 25, 1787, and the marines on the Prince of Wales celebrate with a dinner of pork and apple sauce, plum pudding and rum, while their convicts below mark Christmas with a flash outbreak of scurvy that spreads through the prison deck.

Early January now and in the prison cells of Lady Penrhyn and Charlotte, whispers are shared about the nearness of the NSW coastline. They are close to the end. They can feel it. Botany Bay. Land. And land means survival. Land means a new beginning.

But Neptune, God of seas and southern oceans, is not finished with the First Fleet yet. He saves the worst for last, an unprecedented storm — the most devastating of the eight-month voyage — rising up from the deep blue to damage six of the seven ships in the rear convoy.

“The sky blackened, the wind arose and in half an hour more it blew a perfect hurricane, accompanied with thunder, lightning and rain,” writes surgeon Arthur Bowes Smyth.

“In an instant as we sat at table, the cloth just removed, the ship was laid alongside so very much that it alarmed everybody. Some prodigious flashes of lightning and loud thunder immediately followed … I never before saw the sea in such a rage, it was all over as white as snow … The convict women in our ship were so terrified that most of them were down on their knees at prayers.”

‘I never before saw the sea in such a rage’

London’s exiled sinners on their knees begging God — begging Neptune — to spare them from the tempest so they might live long enough to walk upon the shores of New Holland, if only to walk directly in to a prison cell. One hour later, the storm passes.

The sea calms and the skies clear and, from the deck of Arthur Phillip’s lead ship, Supply, officer Philip Gidley King sights land.

“Saw the land from WSW to NW and at the same time saw the hill resembling the crown of a hat,” he writes. “We stood within three miles of the shore … excepting a few sandy beaches, the cliffs of the shore are very steep and a great surf beats on it. The hills are clothed with a verdant wood and there are many beautiful slopes covered with grass. In running along shore we saw a number of cascades of freshwater falling into the sea from the hills.”

It’s night when Captain John Hunter, aboard the ailing Sirius, leads the rear convoy into Botany Bay. It’s the evening of January 19, 1788. The First Fleet ships are reunited and anchored beneath four stars in the night sky that twinkle in the shape of a cross.

It’s so black inside the prison deck of transport Charlotte that Mary Braund can’t see the face of her baby girl at her breast.

“Why have we stopped?” Mary whispers.

A female voice without a visible owner echoes across the darkness.

“We made it.”

-

PART 1: Told through the eyes of Australia’s youngest convict, eight-year-old John Hudson, this is the First Fleet as you’ve never seen it.

PART 2: The fleet sets sail from England, a young child, would-be mutineers and a convict planning escape aboard.

PART 3: Becalmed on stifling oceans, officers record their low opinions of the female convicts and order hellish punishments for four of them.

PART 5: Confronted by the limitations of Botany Bay, the First Fleet leader rowed north and discovered a body of water beyond his dreams.

PART 6: Arthur Phillip had a brilliantly simple idea for turning the colony from a prison to a community.

ARTHUR PHILLIP: “The first and finest white Australian”

MORE: Captain Cook rediscovered