Cromer High students recall teachers, sex and drugs

For the first time in their own words, traumatised former students blow the lid on Cromer High School and its teachers.

A podcast about a missing woman was determined to unearth new evidence on a probable murder. What no one expected was that it also would open a Pandora’s box of secrets and lies and cover-ups of sexual misconduct and abuse at high schools in Sydney and beyond.

During the past 10 weeks, The Australian’s investigative podcast series The Teacher’s Pet has probed the unsolved disappearance of a young mother, Lyn Dawson, from Bayview on Sydney’s northern beaches in 1982.

Her husband and suspected killer, former rugby league star Chris Dawson, was in an intense sexual relationship with a teenager, Joanne Curtis.

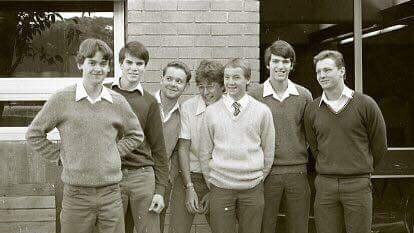

Dawson — who asserts his innocence — was a sports teacher at Cromer High School and 16-year-old Curtis was one of his students when the affair started.

The trickle that would become a flood began with a call to The Australian from Robyn Wheeler, Cromer’s 1983 vice-captain, after the podcast’s first episode.

Her tale was about a pack of teachers preying on 15, 16 and 17-year-old girls on the northern beaches. She has since been joined by many other voices.

As adults they are saying it wasn’t right then and isn’t now, and they are gathering together to share stories and demand an investigation.

Below, in their own words, three former Cromer students describe events that would shape the rest of their lives.

ROBYN WHEELER

It was 1979 and I was 13 years old. And it was my first trip with a school sports team. As the baby of the team, I was excited but also scared. I needed those girls to like me so I could be a part of their team.

We arrived at a motel and had dinner, then everyone went to shower and returned in their pyjamas. I hadn’t been away like this before and my main concerns were around my ability to fit in with girls, who were two, three and four years my senior. We had three teachers with us: our coach and two chaperones. For reasons that now seem inexplicable, the school had sent a team of girls away with three male teachers and no women. They were really familiar with the older girls.

I was surprised when the teachers arrived in the evening in the girls’ room with bags of alcohol. Everyone started drinking, so I did too. I kept up in the drinking games — downing a drink at each loss of a point or failure to answer a question correctly. It was the first time I’d ever been drunk and I felt that it was some sort of initiation.

But it didn’t end well. I left the room as it was spinning, searching for cool air and a place to lie down. I was in the garden in my pyjamas, at an address completely unfamiliar to me. I was vomiting. I somehow got to bed — I think courtesy of two concerned teammates.

The coach, once of the school’s physical education teachers, approached me on the way to breakfast, smiling. I felt sick. “I wonder what your father would say if he heard how drunk you were last night?” he ribbed me.

My father was an office-bearer on the school Parents & Citizens Association. He had made no secret of his impressions of some of the teachers, or of the school’s leadership. Dad had told a roomful of people that the lax attitude to discipline — among teachers and students — was embarrassing. I can imagine now how they would have thought him highhanded, uptight and overly strict.

Those three teachers, and at least three others, passed girls around like a bong at a beach party. Randomly, casually and knowing that, if caught, nobody was really going to do anything about it. And if parents confronted the teachers or deputy headmaster, it appeared to make little difference. The girls kept doing what their parents had tried to stop because, left at school each day with a pack of predators, they were outwitted and outnumbered.

Sometimes the predator teachers stuck to one girl for a period of time and sometimes they “did” the girls in groups. They neutralised reluctant girls’ protests with booze and pot. Other times the girls went willingly. Unsurprising, really — coercing impressionable 15, 16 and 17 year-old-girls in the late 1970s didn’t take a genius intellect. Particularly when you’re part of a pack of predators and your daily environment is set up for you to take whatever you want. But when my coach asked, “I wonder what your father would say if he heard how drunk you were last night?” I didn’t respond as he would have liked: “Probably the same thing he’d say if he knew how drunk YOU were last night.” Wink. Smile. Walk away. Throw up.

Between my mouthy response and my dad’s unwillingness to shut up, I was left alone. What coach had been trying to do — create a secret between us — hadn’t worked. My personal exclusion and safety were a rarity at our school and in those sporting circles during the 70s and 80s. At least three dozen girls were coerced into sex over the ensuing decade at Cromer High and other local schools. Some of them moved on, some stayed put. But others became ghosts: hollow people you would see around the city occasionally after you moved away from the peninsula. When you looked into their eyes, there was nobody there.

HELEN PRIDEAUX

I was 14 when I first walked through the gates of Cromer High School in January 1978. I had started at new schools many times previously: our family was transferred all over Australia for business. I was quite confident I’d be OK; nervous, but I’d be OK.

I was lucky that I knew at that young age where I wanted to be in a few years. I knew the classes I needed to excel in to achieve my dreams: English, art, technical drawing. And I was used to a tough school environment: the skinheads and sharpies had been the rulers of my previous school.

But it wasn’t OK. I quickly understood that this school was a whole different game. I shared my fears and concerns with my parents within the first few days. But I was a child and I may not have been completely clear. I didn’t want to alarm or upset them, so I agreed to give it more chance.

I soon came face-to-face with the reality of this “educational” environment: drug and alcohol use onsite by teachers and students. Chaos in classrooms; students warning me to steer clear of certain teachers.

One teacher held a high position in the school’s hierarchy and his departures from the room were constant and lengthy. I was one of only two girls in that classroom that first year and the backdoor into the grassed alley behind the block was in constant use by male classmates. It was the perfect place to inhale from that bong or scull that flask. I was harassed constantly as there was no supervision; there was no adult in charge.

That 30-something male school counsellor in charge of student care doesn’t appear to believe what you’re telling him. He rolls his eyes and tells you it’s not that bad.

Then there are the celebrations: the birthdays, the ends-of-term, the social nights at our local, the graduations from years 10, 11 and 12. And they’re all at the Time and Tide pub. There’s the beer garden, the music, the coloured lights. And there’s all of us.

There’s also the group of male teachers watching, waiting, the drinks appearing. Thank you, that’s so nice. The evening is over, you walk with your girlfriends, it’s always safer in a group. But then that teacher can give us a lift. Thank you, that’s so nice.

That warm alcohol feeling, it’s a hot night too and our dresses are clingy on our almost adult bodies … We’re all laughing and happy, we drive around and girls depart one by one. But then I’m the last girl in the car.

The car stops two or three blocks away from home. What, why?

“Oh, just shut the f..k up!”

No. This is wrong, you are so much older than me. I push him away. I get the door open and I run. I feel sick and ashamed. I’m hiding in a stranger’s garden, crouched in a bush, waiting for the headlights to disappear.

And then on one of those early summer days in 1980 I know it’s almost over and I can finally breathe. But I’m visited by a school friend.

The tears are rolling down her face, she can hardly breathe, she’s sobbing as she describes the night that has just passed. She didn’t escape her predator, she couldn’t jump from the car, run or hide. There was no lucky escape for her. One of those “caring” male teachers raped her.

I don’t believe I was of much help to her. I remember feeling total despair, knowing no one would believe this.

PHIL WEBSTER

As a young Year 9 student at Cromer High in 1980 — some of my classmates had turned 15, while I was yet to turn 14 — I remember him saying: “I hope to be chasing my wife around the bedroom when I’m 99.”

I pictured him doing just that … naked with his wife, older, but in love and still having a healthy sex life. That is the gist of what he was trying to teach us.

That sex between two consenting adults was the way to go. Although I never met Lyn Dawson, Chris Dawson was my sex education teacher at Cromer High. My idol, my role model: the first-grade rugby league player.

Dawson and student Joanne Curtis were going around together. I knew it. Except she was in Year 11 and he was a teacher. I could see it. My friends agreed and it was no big deal. He wasn’t teaching us any more anyway; he moved to another school.

My sports team at Cromer was the best school squad in NSW in 1982 and 1983.

We played in front of hundreds of fans in finals. We made the local papers. We got recognition at school. We had an awesome coach, a male PE teacher.

But he had his flaws. He was prepared to share them with us too. You see he “had a thing for young girls”. That’s what he told me. From a school down the south coast to Cromer High, he said he just loved them young. He waited, though, until they were 16. He boasted after school that he’d had sex with girls during the day. They would have free periods at the same time as him and “we shag them on the crash mats”, he told me proudly.

So it was no surprise when he announced he was seeing her. She was in my year and by that time we were in Year 11. She was 16 and had just broken up with her boyfriend — my mate — to be with our coach. How could the schoolboy compete? He only had a BMX bike and long walks home, while our coach had a van and could drive her. Anywhere.

I realised it wasn’t just Dawson and our coach. In Year 10, I watched a girl I thought was really pretty ask a teacher: “Why is the ocean blue from a distance but when you walk down the beach and pick the water up in your hands, it’s clear?”

“That is a really great question!” he said. “The ocean is a reflection of the sky, so that’s why it looks blue on a sunny day, and grey when it’s cloudy.”

They were completely immersed in the exchange, almost like they were the only two in the room. And I just knew then and there that there was more to their teacher-student relationship. I just knew they were sleeping with each other.

Not long after that class, in the same academic year, I walked past a house and saw my geography teacher’s car parked out front. I said to my friend: “Is that where he lives?”

“No, stupid. That’s where (she) lives and he’s at her house now!”

There were so many other stories about teachers and students but the PE teachers are my strongest memory.

They were everywhere we were: out with the girls in our year; at the pub together; at the beach together.

Coach would often pick me up in his car with her and other friends. We’d go to North Sydney. He was fun like that and wouldn’t drive drunk, but he was with her.

One weekend we went to her parents’ weekender. There were about 10 of us. She invited the coach and he stayed the night with her in the main bedroom. We didn’t think it was wrong — just a bit different.

Years later I heard they’d broken up. Maybe it lasted two or three years after school. But he stayed at Cromer High and pursued other girls once they turned 16.

What did I learn from the men I looked up to? My own dad wasn’t much help after he was thrown out by my mum.

My elder brother moved out when he was 18. It was just my mum and me, and she told me to treat women with respect.

But that wasn’t what I was seeing at school. I saw teachers having fun with girls. Like a fringe benefit of the job. Coach told me: “Once they turn 16, they’re legal.”