Commonwealth of gold

This is the arena where stars of the future first learn to shine.

If the Commonwealth Games didn’t exist, the Australian Olympic Committee would have had to invent them. Simple as that. In the multi-layered world of sport, there aren’t too many better or more direct examples of cause and effect.

Yes, it must be conceded, there are any number of celebrated cases of Australian athletes winning Olympic gold without having had the benefit of competing in an earlier Commonwealth Games.

But for every Kyle Chalmers, whose freakish ability swept everyone aside in the 100m freestyle in Rio de Janeiro in 2016 when he was just 18, or Matt Mitcham, who broke the Chinese diving stranglehold to win the tower gold at the 2008 Beijing Games at his first major meet, there was always a Ralph Doubell who could place only sixth in the 880 yards at Kingston, Jamaica, in 1966 before winning the Olympic 800m gold in Mexico two years later.

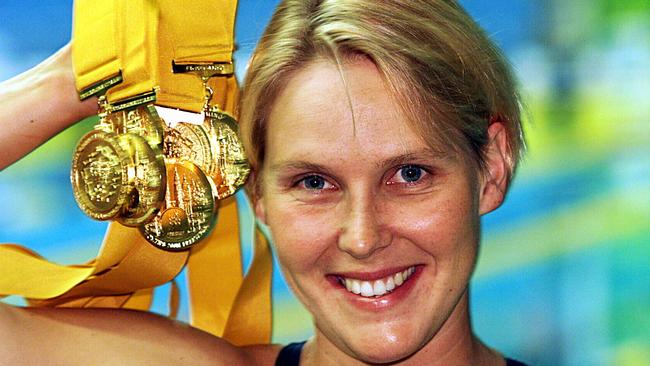

Or a Susie O’Neill. In the years before she passed through the chrysalis stage to emerge as Madame Butterfly, O’Neill nibbled at glory by taking the silver in the 100m butterfly at the 1990 Auckland Commonwealth Games.

Sometimes, ready or not and heaven help them, talent cannot be suppressed. For everyone else, as the caption goes, there are the Commonwealth Games.

In the span on an event that has lasted 88 years — the Commonwealth Games began life as the Empire Games in the Canadian city of Hamilton in 1930 — there will always be instances of athletes taking minor steps before sprouting wings.

But it is such a common tale that the doomsayers who argue that the Commonwealth Games have outlived their usefulness and should be scrapped need to pause for a moment and reflect.

There is, as well, the sheer convenience and, dare it be said, profitability of the Commonwealth Games. Australia has hosted only two Olympic Games, in Melbourne in 1956 and Sydney in 2000. Brisbane and its surrounding cities — including the Gold Coast — are making noises about their intentions to stage an Olympics sometime in the future, but 2024 and 2028 are already taken which means 2032 is shaping as the earliest possibility.

Yet in those 88 years, the Commonwealth Games have come to Australia five times, twice within the past 12 years, with Melbourne hosting them in 2006. And each time they have delivered a dividend that has left the Australian Commonwealth Games Association well cashed up — perhaps not quite to the same degree as the Australian Olympic Committee but certainly well enough to sustain itself into the future.

Unlike about 40 per cent of the Commonwealth, Australia does not have a unified Commonwealth and Olympic Games body. So, throughout their history, the AOC and the ACGA have been independent and occasionally fierce rivals, but both are aware they are working towards the same end. In the lifespan of athletes, it is always the Games — Olympic and Commonwealth — that stand out as the peaks in the mountain range.

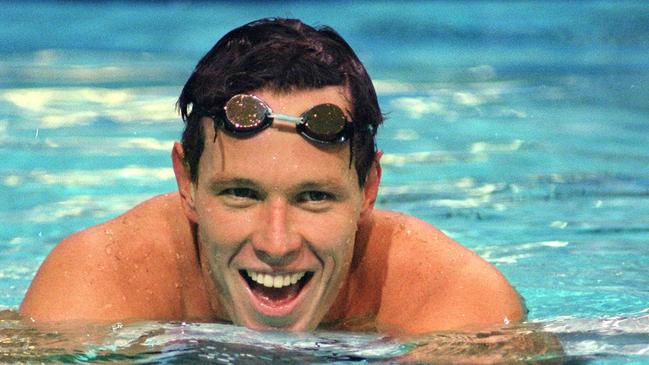

Kieren Perkins can’t say for certain whether he would have won gold in Barcelona in 1992 had it not been for the experience he had in Auckland two years earlier. All he knows is that the Commonwealth Games prepared him in ways he hadn’t even anticipated.

When he fronted up in New Zealand, it was to his first international competition. Indeed, he had won his first Australian title medal only a few months earlier at the Commonwealth Games trials in Adelaide, where his performance in taking the 1500m freestyle silver was almost totally overshadowed by the curious tale of Glen Housman breaking the world record in the heats but inexplicably not stopping the clock.

All eyes then were on Housman in Auckland to see if he could tidy up his unfinished business — sadly, his moment had passed and he never did capture Vladimir Salnikov’s seemingly unbreakable world record — but while he dutifully won the gold, it was silver medallist Perkins who was shaking things up in monumental fashion, breaking 15 minutes for the first time to signal his arrival on the world stage.

It was in Auckland that Perkins discovered he was, as he put it yesterday, “a notoriously bad heat swimmer”. His coach John Carew, who died in 2008, might have phrased it slightly differently but together they recognised they needed to make changes in Barcelona two years later. So Perkins added the 400m freestyle to his repertoire in Spain and, ironically, darn near won his first Olympic gold — he placed just 16-hundredths of a second behind Russian Evgueni Sadovyi — in what was no more than his warm-up event for the 1500m.

“It was a way of getting myself going … blowing out the cobwebs, as we used to say,” says Perkins, who also raced in the 4 x 200m freestyle final in which Australia was disqualified.

When Perkins reflects on Auckland, it wasn’t the swimming that tested him — aside from Housman, fellow Australian Michael McKenzie, who took the bronze, and assorted threats from Canada and Britain, he concedes the depth wasn’t all that stunning — but coping with life in the village.

“The whole rigmarole … you’ve got to get buses everywhere, you’ve got to go in and out of security, you’ve got to go to the dining hall to get food. The whole process is so different to every other meet you go to. Everywhere else, because it’s only swimming, everything is geared towards swimmers. But at the Commonwealth Games, because there are so many different sports and so many different countries, the whole thing is bigger and more complex. I wouldn’t say it is a mini version of the Olympic Games but it is a complete taste test. Everything you confront at the Commonwealth Games you will find at the Olympics.”

He fails to mention having to squeeze into beds that may well have been too snug a fit for his 194cm frame or trying to get some sleep when the 1500m freestyle is scheduled for the last day of swimming and pretty much everyone else in the team is ready to party. But it all comes into the mix that every aspiring Olympic champion must learn to conquer.

Perkins doesn’t recall being particularly “starstruck” at the village — and he probably was a showstopper himself at the Atlanta and Sydney Games — but he can recall bumping into Steffi Graf and Carl Lewis in the Olympic food hall, not something that happens at everyday swim meets. But because Perkins had encountered one of his childhood heroes, Canadian swimmer Mark Tewksbury, at an earlier Commonwealth Games, it meant his chance meeting with royalty from tennis and track and field was merely memorable — not distracting.

Cycling champion Anna Meares vividly recalls her first Games experience. It came at the Manchester Commonwealth Games in 2002 and she always felt grateful to the national selectors who set her on the path to greatness even though technically she didn’t feel ready for it at the time.

“I almost didn’t get selected because I was four-hundredths of a second off the qualification time for the 500m (time trial),” she recalls. “So Cycling Australia at the time said: ‘Here’s this 18-year-old girl who missed the qualifying time by the smallest margin, (let’s) give her the opportunity, give her the experience and see where that can project her career.’ ”

Neither Cycling Australia nor anyone else could have predicted that the trajectory of her career was about to intersect with that of another shooting star, Victoria Pendleton of England. Across three Olympics, the two champions would duel before Pendleton announced her retirement after losing to Meares in the sprint final at the London Games of 2012. She ended her career with two Olympic golds, one silver. Meares, who would soldier on to the Rio Games, matched her two golds and a silver but also added three Olympic bronze medals.

But it was in Manchester that they first brushed wheels. “There are so many pages that are written throughout sport because of Commonwealth competition,” she says. Unlike Perkins, who had time to regroup from a poor start or a sloppy turn throughout a race that lasted almost quarter of an hour, Meares quickly learned in Manchester that she had no time for errors.

“(It was) a whole different perspective on high performance and the elite stage and actually delivering at those key moments of your career — one chance every two years, perhaps every four years, to get a race right that lasts for 33 seconds, which is the 500m. You put a young person in that environment, it’s incredibly stressful, huge pressure, high expectation.

“There’s no other way that you get to be in that environment, a multi-sport environment, all the things that are involved — security, marketing, media, sport, coaching.

“I was able to visually see, physically feel, what those environments can do to you as a person and in the two years between my first Games in 2002 and my first Olympic Games in 2004, I grew so significantly. I did a lot of psychological work, I learned a lot about myself, how I could better perform under pressure, how I could focus, how I could really convey my story and my passion for sport and representing my country because I can guarantee you, that first time around, I felt like a deer in the headlights.”

It’s a common feeling. Diver Melissa Wu was just 13 when she competed at the 2006 Melbourne Commonwealth Games. She looked like a tiny waif standing at the top of the 10m tower, preparing to throw herself off, but it was toughness that saw her selected and toughness that got her through. Now 25, she is a seasoned and well-decorated competitor and, incredibly, preparing for the second home Commonwealth Games of her career.

“Some people don’t ever get to do one Games at home, let alone two,” Wu says.

“Melbourne for me is where it all started. And to be able to do one home Games at the start of my career to start me on my journey to the Olympics and then to be able, at the back end of my career, to do another … I couldn’t ask for a better way.”

And still she is not finished. “I’m hoping to go to Tokyo in 2020.”

For Chalmers and for sevens rugby playmaker Charlotte Caslick, these Games are about consolidation. They went to Rio in 2016 as virtual unknowns, they returned home to superstar status, Chalmers as the winner of the most fabled event on the Olympic swimming calendar, Caslick as architect of Australia’s gold medal win in the inaugural women’s rugby sevens. So that makes the Gold Coast Games different. Now they have become the hunted. Again, it is good preparation for what awaits them in Tokyo in two years.

Ian Chesterman, who has been chef de mission for the past six Australian teams at the Winter Olympics and is set to lead the Summer Olympics team to Tokyo in 2020, has no doubts whatever that the Commonwealth Games remain highly relevant. “You only have to see that from the level of engagement from fans who are watching on television and turning up to watch the competitions, wherever they are,” says Chesterman, who was the ACGA’s media manager from the Melbourne Games through to Delhi in 2010.

“Every athlete who’s been to a Commonwealth Games and then to an Olympics or the Olympic Games back to a Commonwealth Games … both rate very highly and both as an important part of developing their career or rounding out their career.

“And in terms of sporting relevance, they are the absolute world championship of sports such as netball and lawn bowls that don’t have the opportunity to have an Olympic Games. These (the Commonwealth Games) are effectively their highest level of competition.”

Other multi-sports competitions have come and gone. Events such as the Goodwill Games have had their day. They were seen as a means of thawing the Cold War through sport but inevitably began to lose their way after the Berlin Wall came down. They lurched through to 2005, with even Brisbane staging an edition in 2001, but they were held for the last time in 2005. The irony is that founder Ted Turner’s hopes of reviving them are looking brighter than ever as a new Cold War begins to grip Russia and the West.

But the Commonwealth Games are Kevlar-coated. The Empire has gone; so, too, the Commonwealth to all noticeable respects, while republicanism is pressing in from all sides, most especially in Australia.

Yet the Games continue, not just surviving but prospering. Can it be that of all Britain’s gifts to the world, good and bad, they have proven to be the most enduring?

Additional Reporting: Nicole Jeffery