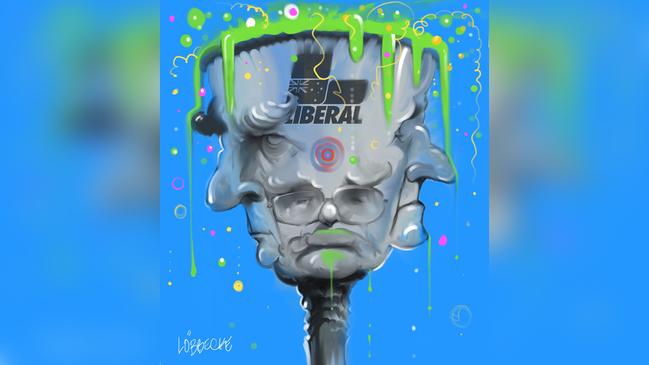

Broad church teeters on a narrow reactionary base

If the Liberal Party truly is a ‘broad church’, how can it’s base be so narrow, reactionary and out of touch with the mainstream?

You know the Liberal Party is in a battle for its soul when Senate president Scott Ryan laments the way the party is being perceived.

The target of his criticisms, in a pointed interview with Radio National’s Fran Kelly, was reactionary forces within the parliamentary party and among the commentariat. Ryan chose not to name names but his criticisms were directed at commentators who offered free advice to the Liberals without ever having been involved in the party, and colleagues who perhaps hadn’t thought very deeply about what made someone a Liberal.

The contradiction in this debate is the John Howard notion that the Liberal Party is a “broad church” — yet, according to warriors such as Tony Abbott, apparently “the base” represents a narrow brand of conservatism that is increasingly out of touch with mainstream thinking.

If the party truly is a broad church, how can the base be so narrow? Surely a party designed to appeal to a broad church by definition has to have a broad base?

The problem for the Liberal Party is that it is perceived as dominated by climate-change deniers and opponents of issues such as same-sex marriage. It is electoral poison among younger voters. Added to this is a gender problem. Women aren’t joining the party’s ranks and, even when they do, they struggle to get preselected.

It’s worth remembering that the Liberal Party used to draw disproportionately on female voters because the unions were so culturally blokey.

Ryan’s point is that you can believe in climate change and still vote Liberal (or be a Liberal). The same goes for other issues and causes. But unfortunately the reactionary nature of campaigning by the hard Right suggests otherwise, turning the party into an unappealing option for many voters.

We saw this week the party’s progressives standing up in the wake of the disastrous Victorian election result. Kelly O’Dwyer’s criticisms of the government and how it is perceived were especially pointed. But perhaps the more interesting development has been the strident way moderate-leaning Liberal voters have been prepared to lodge protest votes in the wake of Malcolm Turnbull’s political demise. This happened in traditional Victorian state seats as well as in Turnbull’s old seat of Wentworth.

To be sure, Ryan is no moderate, far from it. He would consider himself a federalist and an economic dry, twin principles that embrace the historical roots of the party and the modern incarnation following the heady debates of the 1970s and 80s. And while the good senator wouldn’t describe himself as a campaigner for conservative causes, he’s certainly conservative by nature. He is inclined to defend institutions and look for ways to slow down change such that ideas are sufficiently pressure-tested before new policy scripts are adopted.

This Burkean brand of conservatism is quite different to the bastardised modern iteration that has more in common with reactionary politicking. The problem with self-stylised conservatives today is that they are readily prepared to tear down institutions if it advances their campaigning cause. They also appropriate historical figures such as Liberal Party founder Robert Menzies, distorting his philosophical approach when doing so.

Menzies was a Victorian when the state was the jewel in the crown for the Liberal Party. Today the state is increasingly marginalised by the grab for party power coming out of NSW and Queensland. NSW has always seen heady debates between left and right within the party, with neither faction embracing the nuance of progressive and conservative thought emanating from Victoria.

Differences between these groupings have become increasingly polarised around social issues, with the once proud tradition of dry economic reform supported by both groupings no longer prevalent.

The merger of the Liberal and National parties in Queensland has pushed Nationals’ influence into previously Liberal divisions. The impact of this distorts the role of Queensland within the Liberal Party nationally. It also sees both parties more willing to stick their noses into each other’s business.

And this is happening as differences between these state divisions of the party are causing serious policy frictions — on energy and climate policies, on immigration and social policy settings. These tensions are made more difficult when Scott Morrison tries to be all things to all people on some of these issues.

And of course the nature of the modern media — 24-hour news — amplifies dissent when there is lots of it in Coalition ranks; not only because of policy divisions but also personality differences courtesy of the Abbott-Turnbull feud. Such differences between Howard and Andrew Peacock mattered less because they fomented in opposition.

It was Menzies who said: “We took the name ‘Liberal’ because we were determined to be a progressive party … in no sense reactionary.” While there have been debates since those words were delivered as to what Menzies meant by progressive and reactionary, he certainly wasn’t calling for the Liberal Party to be rooted in a conservative world view opposed to progressive thinking, nor a reactive populism that went against traditional liberal values.

The hard Right of the Liberal Party seeks to claim Menzies as one of its own, or indeed Howard. In truth neither former prime minister, the nation’s two longest serving, fit into that ideological grouping. Howard was too pragmatic to put him in that box, and while Menzies appears conservative today, for the times in the 1940s, 50s and 60s he could hardly be characterised as overtly conservative. Using a political figure such as Menzies to justify being conservative about progressive causes such as same-sex marriage is ridiculous. Few, if any, politicians, certainly not political leaders, supported such a policy change 20 years ago, much less in Menzies’ day.

While Howard was socially conservative, his approach to government was dominated by his economic dry world view. Such thinking started in opposition when he supported many of the Hawke-Keating micro-economic reforms; indeed, he wanted to go further. In government, Howard introduced a GST, reformed industrial relations and focused on privatisation and paying down government debt.

And it’s worth remembering his age made him more conservative than many of his ministers; certainly when seen through the prism of debates today. It has been more than a decade since his decade-long reign ended. Had Peter Costello taken over in Howard’s final term it’s likely he would have apologised to indigenous Australians and more rapidly embraced a market mechanism for addressing climate change.

I get the impression our new Prime Minister underestimated how deep the divisions were when he took over the poisoned chalice.

Peter van Onselen is a professor of politics at the University of Western Australia and Griffith University.