Balkans war criminals at liberty in Australia

On the steps of the Opera House, Miroslav Mlinar portrayed himself as a passionate nationalist. The truth was far darker.

Twenty years ago, a youthful and enthusiastic Miroslav Mlinar stood on the steps of the Sydney Opera House imploring thousands of his fellow members of the Serbian diaspora to support their motherland. At the time, bombs were raining down on Belgrade as NATO desperately tried to bring an end to the vicious battles arising from the decade-long break-up of the former Yugoslavia.

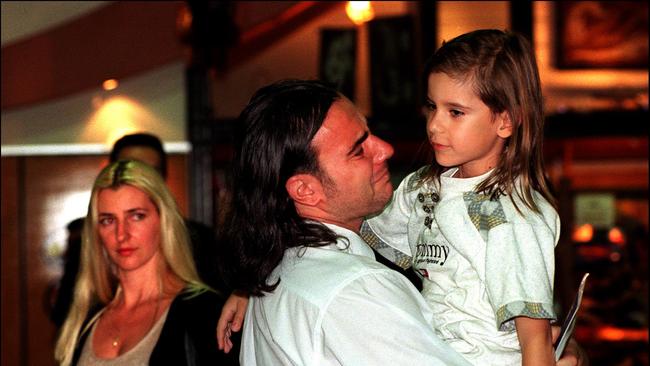

Shortly after, Mlinar, who had been living in Australia for six years and had become an Australian citizen, decided to return to the Balkans to fight. Aged 31, he bid goodbye to his wife, Sandra, and seven-year-old son, Zoran, and left his interior design business in Sydney’s inner-city Pyrmont.

In an interview with The Australian at the time of the Opera House rally, in March 1999, he said Australia was wrong to support NATO. This should have raised eyebrows among Australian authorities. “Who is going to protect my family?” asked Mlinar. “The Australian embassy? (Then foreign minister) Alexander Downer? It’s not fair.”

Mlinar portrayed himself as a passionate Serbian nationalist in the front-page story. There was no mention of the fact that he was already a convicted killer, having been involved in one of the most brutal atrocities of the early Balkan war.

In 1995, two years after moving to Australia, Mlinar was convicted in absentia in the Croatian Supreme Court for taking part in the 1991 Skabrnja massacre, one of the bloodiest efforts by Serbian paramilitaries to terrorise the Croatian population.

He was sentenced to 20 years’ jail. Thirty mainly elderly villagers and 13 soldiers had been tortured and killed in the massacre.

The Weekend Australian can now reveal that months after the Skabrnja massacre, Mlinar had teamed up with the feared Serbian paramilitary leader Arkan, whose Tiger units were considered the most vicious.

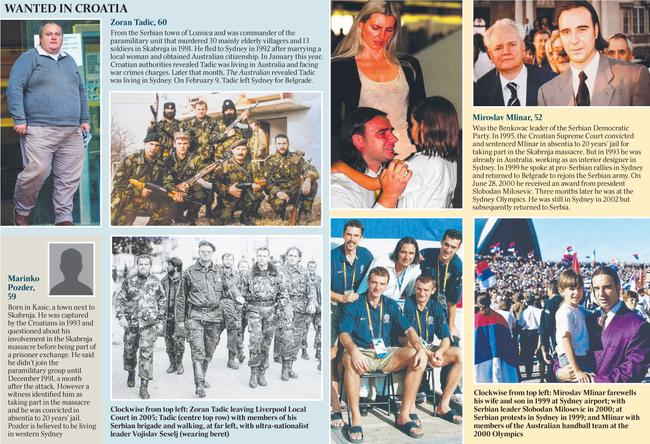

However, in 1993 Mlinar decided to hide in plain sight on the other side of the world, using his own name to establish a Sydney design studio. He was highly active in the local Serbian community, even helping to establish a handball team in western Sydney. Mlinar played goalie and wanted to represent Australia in handball at the Sydney Olympics. In the end, he had to settle for the role of enthusiastic supporter, proudly posing with four other Serbs who had made the Olympic team.

Incredibly, he was able to commute at will between Serbia and Australia for the entire decade — 1993 to 2002. During this time he even had a meeting with Serbian leader Slobodan Milosevic.

Fast forward to 2016 and Mlinar was living in Belgrade. That year he met Russian President Vladimir Putin and had a reunion with the ultra-nationalist leader of the Serbian Radical Party, Vojislav Seselj.

Mlinar is far from the only one linked to the Skabrnja massacre who has been hiding in Australia. The Weekend Australian has previously revealed that Mlinar’s commander in 1991 was another Sydney emigre, Zoran Tadic, who last month fled back to Serbia to avoid arrest and extradition to Croatia to face war crimes charges specifically related to the Skabrnja massacre.

Another of Tadic’s men, and a wartime colleague of Mlinar’s, Marinko Pozder, moved to western Sydney, settled in Green Valley and, like Mlinar, was found guilty in 1995 of war crimes in Skabrnja and sentenced in absentia to 20 years’ jail.

From the beginning, Mlinar had been a polarising figure in Croatian-Serbian relations.

He was the local political leader of the Benkovac branch of the Serbian Democratic Party. Benkovac, in Croatia, was the hub of support for the Greater Serbia plan.

It is believed Mlinar arrived in Australia on a special assistance visa in 1993; his highly questionable political background and his paramilitary roles in Skabrnja and elsewhere were seemingly not declared to Australian officials.

When Mlinar returned to the frontline six years later it was ostensibly to rescue injured civilians after the 1999 NATO bombings in Belgrade.

Several months after that he received an award from Milosevic. Then it was back to Sydney for some years. He attended the 2000 Olympics and stayed on, before selling his Sydney house in 2002 and permanently returning to Serbia.

“This shouldn’t happen,” says Gideon Boas, a professor of law at La Trobe University, noting the unobstructed travel.

“I am not suggesting Australia was remiss — as it was incumbent on Croatia to notify Interpol so that these people will be red-flagged — but the backstory is that Australians don’t care.”

Indeed, even during the worst days of the Balkan conflict, it appeared only the feisty football clashes between rival supporters of Croatia and Serbia sparked any concern among Australians over the complex, age-old enmities.

But even now, a generation on from the bitter war, local expat communities continue to be riven with wariness and even fear.

Boas believes Australia should deal with war criminals within the Australian judicial system — as in Britain — rather than dealing with extradition requests that are bogged down in Croatian politics.

It is estimated that scores, if not hundreds, of suspected war criminals — including many who have already been found guilty and convicted — are living in Australian suburbs without any consequences. A war crimes unit that had been set up to find Nazis in the country was disbanded in the 80s and there is no specialist unit currently tracking war criminals who may be here.

Only one war criminal — Dragan Vasiljkovic, also known as Captain Dragan — has been extradited from Australia, following a nine-year legal battle, after this newspaper found him working as a golf instructor in Perth in 2005.

He was convicted of two counts of war crimes in the Split County Court in 2017 and sentenced to 13 years’ jail for commanding paramilitaries called Knindzas around the Benkovac region.

Both Mlinar and Pozder were unmasked after investigations by The Weekend Australian focused on members of Tadic’s unit. Tadic, now 60, was identified by Croatian authorities last January and charged with war crimes in relation to the deaths of 43 people in Skabrnja.

Fearing a lengthy legal battle similar to that faced by Dragan, Tadic left for Belgrade last month, before the Croatians had issued an extradition request to the Australian Federal Police. Croatian police were surprised at the developments, having believed the AFP was keeping a close eye on Tadic, whose mobility is restricted because he is obese.

Notwithstanding his recent health issues, members of his unit have recounted how Tadic was particularly vicious, so much so even his paramilitary troops branded him scum and one gleefully recounted how he once peppered his car in a hail of 30 bullets.

Others have described how power went to Tadic’s head, and even though some of his men had found themselves in the same expat community in western Sydney, they did not stay in contact.

Boas says the circumstances surrounding Mlinar and Pozder, nicknamed “Berto”, are even more puzzling than those of Tadic, who simply beat the bureaucracy in a race to Sydney’s Kingsford Smith airport. When Mlinar and Pozder, along with 16 others, were convicted in the Croatian Supreme Court in 1995, the court listed them as “whereabouts unknown”.

The events of Skabrnja on November 18, 1991, became a terrifying portent of the vicious ethnic cleansing that would, several years later, lead to the slaughter of 7000 Bosnians in Srebrenica. Even now, the Skabrnja atrocity is commemorated in Croatia every year by tens of thousands of people.

The Croatian Supreme Court and International Criminal Court in The Hague were told the Skabrnja massacre was planned when a team of Serbian paramilitaries was pulled together from the Benkovac region in Croatia. They were commanded by Tadic, a Serbian intelligence officer, and others from Loznica on the Serbian-Bosnian border. These paramilitaries were believed to have been supported by Seselj, who had raised tens of thousands of dollars from Australian supporters.

As the regular army tanks rolled into the village, the military rounded up civilians to bus them to holding areas outside the region. But then those villagers who had been hiding in basements — 30 mainly elderly farmers and those unable to flee — were dragged out by Tadic’s paramilitary men and tortured, including being bound in barbed wire and dragged by horses, having their throats slit and their bodies mutilated, or shot at point-blank range. Another 13 Croatian soldiers captured in the town suffered the same grisly fate, including one who had his ears hacked off while still alive and another who was blown apart by a rocket-propelled grenade. The Croatian judge who heard the Skabrnja case described the paramilitaries as particularly cruel.

After going to the trouble of conducting a trial and finding Mlinar, Pozder and the others guilty, the Croatians appear to have failed to notify Interpol of the court decision.

This meant there was no red flag that might have alerted border authorities when the two entered or left Australia.

The case highlights deficiencies in the Australian immigration vetting process, too: these men could use their own names to enter the country without any fear of scrutiny. Then, in assessing applications for Australian citizenship some time after the Croatian court decision, there appear to have been no extra checks conducted with Croatian authorities.

When Tadic appeared before a Liverpool court in 2005 charged with a road-rage incident, throwing an innocent woman into the path of oncoming traffic, his lawyer spoke of his exemplary character and he was given a 12-month suspended sentence.

Pozder is believed to have fled to Serbia this week, like Tadic before him. Mlinar, meanwhile, has spent the past 16 years in Belgrade, a senior supporter of the women’s football team Red Star.

Three years ago Mlinar once more met Seselj, whom he was first pictured alongside four days after the Skabrnja massacre in 1991. Tadic was also in that photo. The two are also alongside Seselj in a 1991 video seen by The Weekend Australian.

Seselj remains the leader of the Serbian Radical Party, despite his conviction for a war crime in The Hague. He has revealed he still has more than $160,000 in Westpac bank accounts in Australia, including some money raised during a book tour of the country in 1989.

In 2001, after the war finished, the Reserve Bank of Australia issued specific rules about payments and credits into accounts held by nearly 200 people from the former Yugoslavia, including Seselj, because they were being investigated for war crimes by the International Criminal Court in The Hague. The rules meant the accounts were effectively frozen.

A spokesman from Westpac said yesterday: “Westpac is unable to comment on individual customer relationships. However, we can confirm that we have in place appropriate controls to ensure compliance with trade and economic sanctions and other financial crime obligations.”

In the financial realm there are signs of firm action having been taken but in society at large, oversight has been minimal, with some of the Balkan war’s most barbaric criminals allowed to drift into Australia at will. Through it all, their adopted country has stood by, seemingly oblivious. Such apathy is, perhaps, this story’s most damning dimension of all.