Asylum-seekers: Europe echoes Australia’s Tampa moment

The EU debate on asylum-seekers is beginning to mirror Australian affairs.

All of a sudden, Australia doesn’t seem quite so far out on a limb with its treatment of boat-borne asylum-seekers. Among the Europeans, public opinion that once ran in favour of accommodating Middle Eastern and African refugees has turned sharply in favour closing the borders, culminating in their very own Tampa moment.

This happened two weeks ago when Italy’s Interior Minister and Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini refused to let the humanitarian vessel Aquarius dock after it had plucked 629 people from the sea off Libya.

Like John Howard in 2001, when the MV Tampa steamed into Australian waters with its cargo of 433 rescued boatpeople, Salvini stood his ground, putting into effect the shaky new populist government’s promise to crack down on unauthorised boat arrivals.

The Aquarius finally made port in Spain, after Malta also denied it permission to berth. Facing slapdowns from France and the Vatican, Salvini, the leader of the nationalist League, was adamant the door would stay shut. Voters immediately rewarded the League with impressive gains in local elections, prompting him to exult: “Clearly, raising your voice — something Italy has not done for years — pays off.”

The Tampa-Aquarius parallel is not the only sign that the tide has turned in Europe, sending it down a path that more closely resembles Australia’s hardline policy of boat turnbacks and offshore processing than the welcome mat that was rolled out in 2015-16 when the refugee flood from Syria added to the weight of people on the move from trouble spots such as Afghanistan, Iraq and Sudan.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel, who set the tone by taking in 1.4 million asylum-seekers in the past three years, was nearly brought down this week after her coalition government split over refugee policy.

The day of reckoning still looms for Merkel, as she succeeded only in putting off for a fortnight the showdown with longstanding ally Horst Seehofer, the Interior Minister and chairman of the Bavarian sister party to her Christian Democratic Union. He has vowed to proceed with the plan she vetoed to start turning back asylum-seekers at the German border.

The drawbridge has also gone up in neighbouring Austria, which has bluntly told the EU it will accept no more refugees. Hungary’s combative Prime Minister Viktor Orban openly derides Syrian asylum-seekers as “Muslim invaders” and has positioned himself as the continent’s most anti-migration leader by fortifying the border with Serbia with an electrified fence topped by razor wire. While Merkel suffered a near-death experience at last year’s German election, Orban romped home when Hungarians went to the polls in April.

After joining Sweden in reintroducing border controls, ultra-liberal Denmark this year drafted laws to confiscate refugees’ cash and belongings to cover the cost of hosting them. The Schengen Agreement, aimed at a borderless continent is now coming apart at the seams.

Britain’s impending exit from the EU next March will exacerbate the crisis of confidence in the European project amid a surge in support for right-wing and anti-migration parties such as Marine Le Pen’s National Rally in France, formerly the National Front. She embraced Salvini’s veto of the Aquarius, saying a “policy of firmness” was the only way to halt the mass arrivals by sea.

Donald Trump, meanwhile, is adamant that he will not be swayed from his election commitment to secure the Mexican border — despite the outcry joined by his wife, Melania, at the heart-rending scenes created by the separation of children from parents accused of illegally entering the US. The kids-in-cages revelations have shown that Trump’s “zero tolerance” policies have a morally challenging downside.

The intensifying debate in Europe echoes the deeply divisive discourse here over boat arrivals. Today’s Newspoll shows the Turnbull government has lost ground to Labor on the question of which side would be best at continuing to control the boats — traditionally a Coalition strength. This reflects the volatility of public opinion in this space, which can be traced back to the Tampa affair all those years ago.

The arrival of the packed Norwegian freighter off Christmas Island in August 2001 was ruthlessly exploited by Howard in the lead-up to the federal election, helping to sink Labor under Kim Beazley. It also provided grounds for the Coalition to bring in offshore processing through the so-called Pacific Solution whereby asylum-seekers arriving by boat were immediately sent to camps on Nauru and Manus Island in Papua New Guinea.

Cruel as it was to the detainees, it succeeded in halting the boats. But Labor scrapped the policy when Kevin Rudd became prime minister in 2007, creating a whole new set of political problems for the ALP when the traffic revived. Again, it played into the Coalition’s hands, this time for Tony Abbott. By then Rudd had been knifed by Julia Gillard, who tried unsuccessfully to revive offshore processing in East Timor and Malaysia. When Rudd exacted his revenge on her ahead of the 2013 election, he did a deal with PNG to hold and resettle detained boatpeople; Abbott as PM extended this to Nauru and ordered the navy to turn back boats.

Malcolm Turnbull inherited a stable policy situation that endures: the people-smugglers, for now, are plying their monstrous trade elsewhere. But the humanitarian plight of those stranded on Nauru and Manus Island continues to plague both the government and the ALP, which under Bill Shorten is under pressure from the left to relax the tough stance on asylum-seekers.

The suicide last week of a 26-year-old Iranian asylum-seeker on Nauru, the third detainee to take his own life there, a month after the death by his own hand of a Rohingya man on Manus Island, has brought the questions into sharper relief.

Turnbull insists the government is doing all it can to resettle in third countries those who have qualified as refugees, but bringing them to Australia is not an option. Shorten says he is against anyone being held in indefinite detention, but has hedged on what more Labor would do except to say in government he would pursue regional agreements including a resettlement offer from New Zealand that was rejected by Turnbull.

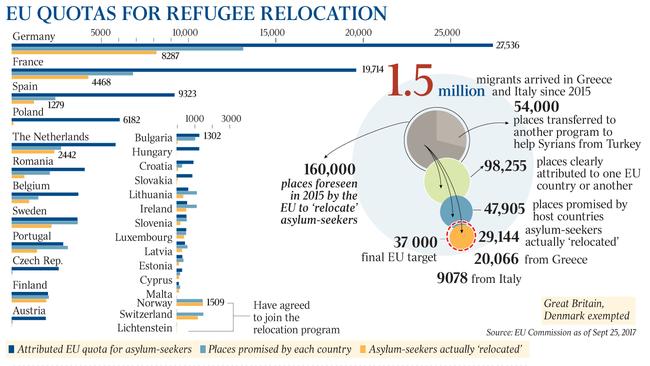

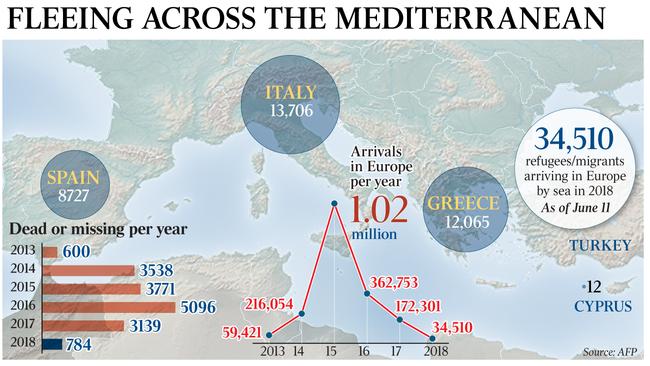

In that respect, the debate here is running ahead of Europe, where the continent has descended into ever deeper division over how to control porous EU borders. This has some surprising dimensions. Under EU law, migrants must apply for asylum in the first country they enter. But this places a heavy burden on nations such as Greece and Italy, which are first in the firing line for asylum-seekers arriving from the Middle East and North Africa respectively.

The Eurosceptic Italian government is now leading the charge for reform of those laws ahead of a summit in Brussels later this month. The battle lines transcend the ideological considerations that dominate in Australia. Western Europe’s most significant anti-establishment government come to power in March when young Italians voted in droves for the League under Salvini and the populist Five Star Movement. Struggling with a bleak job outlook that has been entrenched over the past decade, they backed the parties’ shared anti-immigration stand, laying bare a generation gap with older voters who kept faith with the status quo.

The youth revolt is spreading across Europe, up-ending preconceived notions about the hold progressive politics is supposed to exert on young voters. As ever, self-interest wins out. Almost 30 per cent of Italians aged 20 to 34 aren’t working, studying or in a training program, according to Eurostat, more than in any other country in the EU. Greece comes in next at 29 per cent while Spain’s rate is 21 per cent.

The frustration of young, typically well-educated Italians with the limited job prospects is voiced by Carlo Gaetani, a self-employed engineer in Puglia. Ten years ago, when he was in his early 20s, he voted for a mainstream centre-left party in the hope it would drive economic development in the country’s south. But he felt betrayed when Italy slipped into recession, leaving many of his friends unable to find work. His own opportunities are limited because, all too often, well-paid government commissions go to people with the connections he lacks.

“Italy is collapsing and yet nothing has changed in this country for at least 30 years,” he told The Wall Street Journal. “Five Star is our last hope. If they also fail, I think I will stop voting.”

In Germany, opinion polls show that 61 per cent of the electorate wants asylum-seekers with an open refugee application in another EU state to be turned back, a sobering reminder for Merkel as she fights for her political survival.

Although the influx to Germany has slowed — asylum requests dropped from 745,155 in 2016 to 22,560 last year — the public backlash has scrambled politics in what had been among Europe’s most stable countries, boosting support for anti-immigration populists, who cleaned up at the polls last year and look set to do even better in upcoming regional elections in Bavaria. The border province has been Germany’s front line in the refugee crisis, with asylum-seekers pouring in from neighbouring Austria.

A Civey poll on Monday found that 71 per cent of voters in Bavaria would accept a breakdown of the governing coalition if Merkel continued to rebuff Seehofer’s Christian Social Union.

Urging him to back down, the Chancellor warned that a unilateral policy on asylum-seekers would split Europe and further strain relations with member states feeling the strain of the refugee crisis. Seehofer wasn’t having any of it. He reminded Merkel that it was her decision to open Germany’s borders, and she needed to take responsibility for the consequences. “We don’t have migration under control … people who are banned from entering Germany, as well as those who have applied for asylum or who are registered as asylum-seekers elsewhere in Europe, should be turned back at the border,” he said.

If Merkel is to survive beyond the two-week reprieve offered by Monday’s uneasy truce, she must move swiftly to cut deals with other EU countries to accept more refugees. At the very least, they must commit to the processing of asylum claims rather than putting freshly disembarked boatpeople on the next train to Germany, as the Italians have been accused of doing.

The politics of asylum on the continent are becoming increasingly poisonous, mirroring Australia’s long and tortured journey through this minefield of public policy. But if it is sympathy or understanding the Europeans want, they won’t be getting it from their supposed ally in Washington.

Fresh from his run-in with Merkel at the G7 summit, Trump seemed to relish her predicament, tweeting this week: “The people of Germany are turning against their leadership as migration is rocking the already tenuous Berlin coalition. Crime in Germany is way up. Big mistake made all over Europe in allowing millions of people in who have so strongly and violently changed their culture!”