Al-Qa’ida at 30: legacy of terror still threatens the West

After 30 years, the deadly group’s cycle of violent successes and near-death experiences is yet to run its course.

The first known meeting of the group later called al-Qa’ida took place in the Pakistani frontier town of Peshawar on August 11, 1988. Al-Qa’ida has come a long way from its founders’ original vision 30 years ago, but it is just as dangerous and capable today — and it is not going away anytime soon.

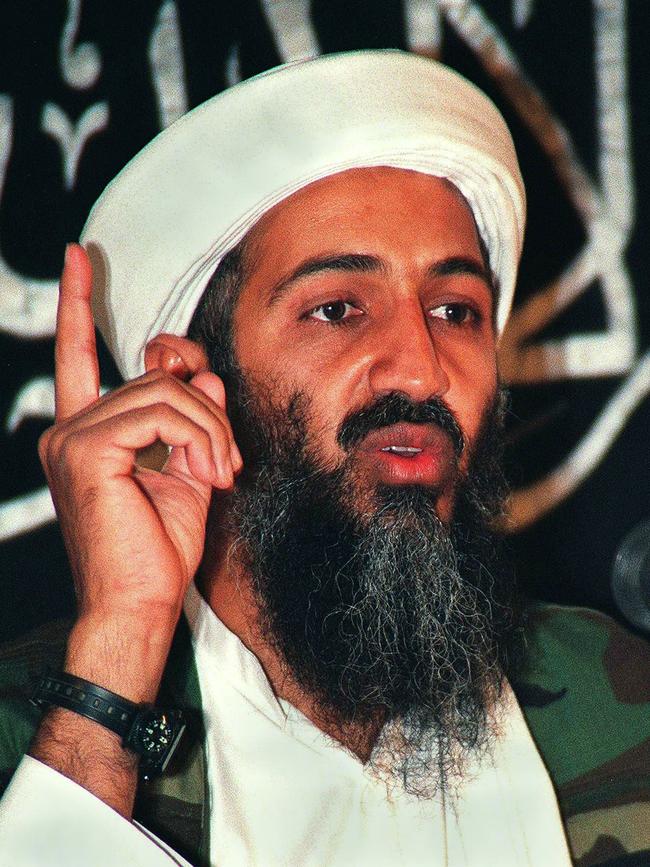

Three decades is a generation: Osama bin Laden’s son Hamza, born in 1989, is now part of al-Qa’ida’s leadership, while children of other early leaders are prominent in some of its affiliates. Those three decades also represent multiple generations of adaptation for an organisation that has evolved from the outset. Al-Qa’ida’s innovation is far from random: it shows a clear cyclical pattern of what we may call “catastrophic success”, followed by near-destruction, evolutionary transformation and recovery.

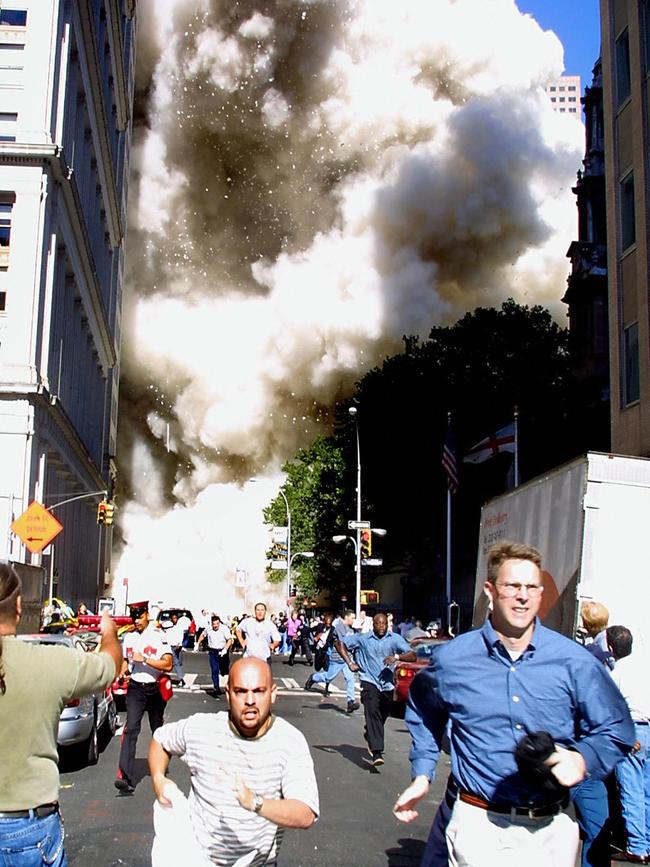

The group’s first catastrophic success was on September 11, 2001. The largest, deadliest, most spectacular terrorist attack in history, 9/11 triggered the war on terrorism and touched off a cycle of conflicts that is still expanding. When the history of the 21st century is written, we may look back on bin Laden as one of its most influential individuals, since we now live in a world shaped by the violence, mass displacement and instability he unleashed, and that Western government responses — most prominently the decision to invade Iraq in 2003 — dramatically exacerbated.

The 9/11 attack took years to plan, and was conducted by a centrally recruited expeditionary team of 19 attackers from 15 countries, trained in Afghanistan and then smuggled into the US. For scale and ambition, it dwarfed anything previously seen; it was also, at $US500,000, the most expensive terrorist attack.

The attack’s impact dwarfed its cost to al-Qa’ida: it killed 3000 people, wounded thousands and caused billions of dollars in direct economic costs. If we also count the wars that followed, the cost (to the US alone) rises to $US5.6 trillion ($7.5 trillion) today, and the dead (for all countries) to about 400,000 — half of them civilians.

The al-Qa’ida that conducted such a sophisticated operation was a large, centralised, hierarchical organisation. It had a leadership council around bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri, various policy committees, an operations planning team and a multifaceted financial and logistical infrastructure. It ran a network of training camps in Afghanistan housing thousands of fighters, and its affiliate organisations ranged from the Taliban regime to a group run by Jordanian Abu Musab al-Zarqawi in the Afghan city of Herat, and allied groups in Africa, the Middle East and Southeast Asia.

The success of 9/11 was catastrophic for al-Qa’ida, though, because the backlash it provoked almost killed the group. Within 12 weeks, its centralised structure had ceased to exist. By early December 2001, the Taliban was overthrown and al-Qa’ida’s Afghan base was crushed. Zawahiri and bin Laden were cowering under airstrikes in the Tora Bora mountains, expecting to die at any moment, while a radio intercept caught bin Laden apologising to his followers for leading them to destruction. Thousands of fighters had been killed, thousands more captured (of whom hundreds were summarily executed by their Afghan warlord captors) and dozens detained in the new US facility at Guantanamo Bay. The network of camps was utterly destroyed, Zarqawi had been wounded and fled (like other al-Qa’ida leaders and their families) into Iran, and the hierarchy was scattered.

The group ultimately survived the first of its near-death experiences and underwent an evolutionary transformation as bin Laden, Zawahiri and other leaders escaped to Pakistan to recover and re-establish the network. But in this second iteration the group was much more decentralised, a looser global guerilla movement rather than a centrally directed terrorist hierarchy. The core group in Pakistan played a propaganda and ideological role, seeking to aggregate the effects of multiple local allies rather than acting as a headquarters or planning hub. Self-recruited, self-motivated individuals mounted attacks in the group’s name, and affiliates in Indonesia, Spain, Iraq, Yemen, Pakistan and Somalia came to dominate the next evolutionary cycle.

Jemaah Islamiah carried out the two Bali bombings and several other attacks in Indonesia; al-Shabab emerged in Somalia in 2006 and soon had cells across East Africa. A powerful al-Qa’ida affiliate arose in Yemen, with ambitions to attack Europe, Australia and the US. A self-selected team, trained by al-Qa’ida but operating on its own initiative, launched the London bombings of July 7, 2005. Affiliates in Pakistan assaulted the Indian parliament and mounted a deadly raid on Mumbai. A cell of Moroccan immigrants in Europe mounted the most strategically important attack of this period — the 2004 Madrid train bombing, which killed 193 people, wounded 2000, brought down the Spanish government and knocked the country out of the “coalition of the willing” in Iraq.

And the most powerful al-Qa’ida affiliate — Zarqawi’s group al-Qa’ida in Iraq — achieved the movement’s next catastrophic success, on the back of the US-led invasion. After fleeing to Iran in 2001, Zarqawi was treated for his injuries before making his way into Iraq to set up underground cells, support networks and weapons caches in preparation for the invasion. By August 2003, five months after the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, AQI had established itself as the leading jihadist faction within the Iraqi resistance, mounting a series of deadly attacks including the Canal Hotel bombing in Baghdad that killed UN special representative Sergio Vieira de Mello and 21 others. By 2005 a deadly insurgency was in full swing and the coalition plan for a rapid exit was in tatters.

For several years Iraq dominated global security and geopolitics, directly (through growing demands for troops and resources for an increasingly deadly war, flows of foreign fighters and spillover of terrorism into neighbouring countries) and indirectly by drawing US and coalition attention away from a deteriorating situation in Afghanistan and enabling rivals such as Russia, China, North Korea and Iran to expand their influence and take advantage of the West’s tunnel vision on terrorism. By the time Zarqawi was killed in mid-2006, AQI had achieved its own version of catastrophic success. The most ideologically extreme of al-Qa’ida affiliates, it was increasingly independent from the al-Qa’ida core, and its anti-Shia attacks had succeeded in transforming Iraq from a war of national resistance against occupation into a horrendous sectarian bloodbath. With AQI at its peak, 2006 was the bloodiest year of the Iraq War.

But again, success brought such a severe pushback that the organisation suffered a collapse. The 2007 “surge”, a response to AQI’s success of 2006, almost destroyed it — in just six months an influx of US troops, an “awakening” in which Sunni communities turned against AQI and a new counter-insurgency strategy brought a 96 per cent reduction in AQI activity, shattering its hold over the population. Iraq experienced a dramatic drop in violence — which turned out to be temporary, lasting until US forces withdrew in December 2010 and the Shia-dominated government reverted to repression against Sunnis.

After this second near-death experience, AQI was eclipsed by al-Qa’ida in the Arabian Peninsula in Yemen, al-Shabab in Somalia, and networks in Pakistan and Afghanistan, while core al-Qa’ida leaders in Pakistan and Yemen promoted an even more diffuse approach of “leaderless jihad” — a self-synchronising, ad hoc approach that was the antithesis of the group’s top-down approach before 9/11. At the same time, survivors of AQI’s collapse — including its new leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, and its regional commander for the Mosul area, Syrian-born Mohammed al-Jolani — sought to learn lessons from their defeat.

The two men drew starkly different conclusions from their experience, as became clear in 2011 when the Arab Spring, the death of bin Laden and civil wars in Libya, Yemen and Syria brought the next wave of evolutionary transformation. This provoked a schism between Baghdadi’s faction, now officially separate from al-Qa’ida and styling itself the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham, and the broader al-Qa’ida network including Jolani’s group — now fighting the Assad regime in Syria as Jabhat al-Nusra. Both groups came from the original al-Qa’ida base, but — like Stalinists and Trotskyists, or rival drug cartels in Mexico — now represented dramatically different approaches.

Baghdadi’s movement doubled down on sectarian hatred and adopted a strategy of advertising its ferocity and extreme barbarity to cow local populations and bolster recruitment worldwide, drawing in individuals inspired by the group’s uncompromising ideology or excited by its violence. The Islamic State quickly grew to thousands of fighters, building up conventional military capabilities such as tanks, artillery and rocket launchers, organising itself as a state-like entity and seeking to mount a conventional war of conquest rather than a guerilla or terrorist campaign. This triggered the next cycle of catastrophic success and near-collapse.

In late 2013 and 2014, having rebuilt itself in Syria, Islamic State struck in Iraq, launching a conventional blitzkrieg that rapidly captured one-third of Iraq and later expanded to about the same proportion of Syria. The group exploited Sunni resentment of Iraqi government repression, and US leaders so distracted by Afghanistan (and so determined to move on from Iraq) that they ignored repeated calls for help from the Iraqi government and warnings from their own intelligence community.

The speed, ferocity and success of its advance in mid-2014 pushed the group to the pinnacle of the world jihadist movement, overshadowed al-Qa’ida (now a bitter enemy), and thrust Baghdadi and his movement into the spotlight.

By 2015 Islamic State controlled more than a dozen cities across Iraq and Syria, a population the size of Singapore, and revenue sources that generated more than $US1 million a day to fund the building of Baghdadi’s self-declared caliphate. Its success brought a huge influx of recruits from around the globe. Besides its central pseudo-state in Iraq and Syria, it had an array of “wilayat” (provinces) in Africa, Afghanistan, Southeast Asia and elsewhere, and an international network — perhaps 200,000 people — of individuals and ad hoc cells acting in its name to carry out attacks inspired by its ideology.

The Islamic State, at its peak in late 2015, was far larger, more sophisticated and militarily capable than al-Qa’ida had been in its pre-9/11 heyday. Baghdadi’s “caliphate” came closer than any group to establishing a state.

Yet, once again, this unprecedented success carried the seeds of its own destruction: politically, because of the sectarian hatred that defined the group’s ideology, and militarily because by operating in the open — with tanks, in cities — Islamic State shifted the conflict from guerilla warfare and terrorism (where nation-states such as the US and its allies struggled) to exactly the conventional forms of warfare in which they excelled. Islamic State fighters stood, fought and died — in Ramadi, Tikrit, Mosul, Raqqa and many other places — as their caliphate was crushed.

Three decades of history suggest we should be extremely wary of triumphalism from US and allied leaders who now claim Islamic State is destroyed. Rather, it is going through its latest cycle of evolutionary change, having dropped back from conventional warfare into guerilla mode, entering yet another recovery and rebuilding phase. Islamic State cells still exist in Iraq and Syria, its network is alive and well in numerous countries, and its provinces — in Africa, Afghanistan, or The Philippines, where last year they captured and held the city of Marawi for five months against a determined counter-assault — are alive and well. Key leaders, including Baghdadi, remain unaccounted for, and the group retains the ability to strike.

Baghdadi’s nemesis, Jolani’s faction — the former Jabhat al-Nusra, now calling itself Hayat Tahrir al-Sham — is by far the most impressive and capable terrorist group on the planet today. HTS controls much of the northwest Syrian province of Idlib. Where Baghdadi emphasised sectarian ferocity, the softly spoken Jolani has adopted a popular front strategy, co-operating with other groups, building alliances, presenting HTS as a moderate, rational version of jihadism, and emphasising the need to oppose Bashar al-Assad and work with other Syrians rather than pursuing apocalyptic global jihad.

Yet beneath its more moderate image, HTS has all the military capability of Islamic State (or of al-Qa’ida before 9/11) while possessing much of the political savvy and talent for social and political work of Shia groups such as Hezbollah. It has a measure of local public support in areas it controls, and the ability to strike abroad — into Turkey, Europe and farther afield. It has a cordial relationship with core al-Qa’ida in Pakistan, yet represents the most mature and capable iteration of the original al-Qa’ida concept pioneered a generation ago by bin Laden.

While increasingly under attack from Russian, Iranian and Syrian government forces, the staying power and survivability of HTS are hard to doubt.

There does exist the possibility — albeit a slim one — that like the Soviet Union in the late 1920s (when Stalin abandoned Trotsky’s notion of global permanent revolution for one of “socialism in one country”, and emphasised Russia’s national interests) or the Islamic Republic of Iran in the 80s (when the mullahs maintained a theoretical commitment to world revolution but acted increasingly like traditional Persian rulers) HTS may settle down into something like an “Islamic Emirate of Idlib”. It might evolve into a state among states within the international system, though clearly an unpleasant one that other governments would seek to contain.

If anyone could pull off such a transformation, it would be Jolani.

Failing that unlikely outcome, we can expect that sooner or later Baghdadi’s faction of the Islamic State will recover, though if history is any guide it will look different next time around.

We can expect a sustained threat in Western countries from ad hoc cells and self-recruited individuals inspired by its ideology. Australia, Europe, North America and Russia will remain targets, as will Israel, India and to some extent China.

While Western military interventions continue — albeit with fewer troops — in Africa, Afghanistan and Iraq, and civil wars carry on in Syria, Yemen and Libya, the forever war against terrorism will rage on.

But as its 30-year cyclical history of growth, catastrophic success, near-collapse and recovery runs its course once more, nobody should imagine that al-Qa’ida — or its heirs, successors and imitators — will go away anytime soon.