A nation loses its voice

A typical obituary could never capture the life and achievements of revered journalist and author Les Carlyon.

-

“Obituaries of people often sound as though they were written by a computer program — educated here, chairman of this, vice-chancellor of that. Printouts rather than lives.”

— Les Carlyon

Easy for you to say, Les. Summing up your life should be simple. All those awards. The accolades. The acclaim that always followed when your prose made it into print. This obituary might have to be written with a bloody big lump in the throat knowing your voice will never be on the phone again, giving advice when it is desperately needed, perspective when it has been lost and inspiration when the well has run dry.

But your life and its many achievements? So straightforward …

Les Carlyon, one of Australia’s most revered journalists and authors, has died after a long illness. He was 76.

Carlyon, a Companion of the Order of Australia for his “eminent service to literature through the promotion of the national identity”, was a Walkley Award winner and newspaper editor who wrote several bestselling books, including …

Blah, blah blah.

You’re right, Les. A computer spitting out a stream of data and ripe cliches. Nothing really wrong with it, apart from being the opposite of what you stood for and how you wrote. You championed accuracy but there was never anything clinical or impersonal about your style. When you wrote about a century-old battlefield you resurrected the dead, allowing us to smell the fear along with the cordite and smoke. When you wrote about sport you managed to make horses sound human. When you wrote about politicians you made humans sound like asses.

Actually, anything you wrote made the rest of us feel like house painters reeking of turps, staring at the Sistine Chapel ceiling wondering how Michelangelo did it.

After a lifetime in journalism — editor of The Age, editor-in-chief of The Herald and Weekly Times, columnist for The Bulletin and Business Review Weekly — it pained you to watch the decline of newspapers.

It was hard to figure out what annoyed you more — that moment when reporters began to wear expensive suits and worry about their “personal brand” or when management types started issuing memos about the need to mobilise external and internal support to achieve corporate objectives.

What was it you said a decade ago?

“The main troubles with journalism are sloppy writing and sloppy editing, advocacy masquerading as reporting, gossip masquerading as reporting, stories that abound in loose ends and cliches, stories that are half-right, stories that insult the reader’s intelligence.

“In other words, most of the problems of journalism are our fault. They’re matters of craft, not ethics. Why … do we talk about everything but the words? The words are the only thing the readers judge us by.”

You were being a little disingenuous there, Les. The verdict might be easy when it comes to your words. But there is so much more to judge you by.

This is the part of the computer-generated obituary where we go back in time and mention you were born here and educated there and …

Blah blah blah.

It’s enough to say you were born in Elmore in northern Victoria in 1942 and grew up in that tough postwar era in the bush. You never liked to talk about it much. You once mentioned how those early years were hard and muttered something about a dirt-poor family living in a home with hessian walls and then, as if realising you had said too much, changed the topic. No wonder words became a haven for a skinny kid with bad eyes. You loved reading Henry Lawson and his outback, with its gnarled and stunted trees and sparse undergrowth. But there was no romance there for you. “The Great Australian Nothingness,” you called it, “ … flat, endless, bad for the soul.”

One of the first books that made you think words could dance on a page rather than just sit in cold type was Tolstoy’s first novel, The Cossacks. It was a little book, just a few shillings and small enough to fit into your shirt pocket. But in Tolstoy you found a writer who knew how to use words, who wasn’t interested in showing off, who wrote as though “he was describing the world to a blind man”. When Tolstoy mentioned a village in the Caucasus, the young Les imagined “huts thatched with reeds, black smoke drifting from chimneys and you know that inside are icons and cockroaches and smoke-stained timbers. You see Cossack men, faces cut from old leather, riding off to hunt boar.”

By 1960 you had made it to the city to become a young reporter on Melbourne’s The Sun News Pictorial, the most popular paper in the country, a masthead where brevity and the reader always came first. You were soon lured across town to The Age where Graham Perkin was launching a journalistic revolution. When he suddenly died in 1975 you were thrust into his seat at just 33. Unlike most editors, you didn’t have to wait for an impulsive proprietor to move you on. Pneumonia and exhaustion got there first.

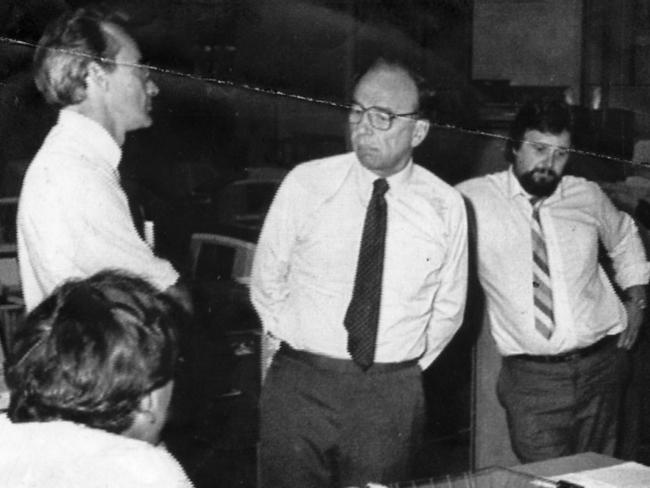

There was a stint teaching journalism in the early 1980s. Well, as long as there was a phone near you and a caller seeking advice on the other end, that never stopped. But this was an official masterclass. Every Friday morning you sauntered into a stuffy room in the bowels of the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, lean as a greyhound, a newspaper tucked under your arm. You would take a drag on your cigarette and a group of rowdy university students would fall so silent the only thing they could hear was the crackle of burning tobacco. It was always practical and knowable stuff; words to avoid, cliches to cull, mangled metaphors to be incinerated along with their authors. Simple lessons that stayed with a generation.

People outside journalism followed your newspaper columns and articles because your words either let them think they were at the movies, or had a seat in history’s front row. Jill Baker was editor of The Sunday Age when the funeral of Diana, princess of Wales, was held right up against Australian deadlines. Of course she asked you to cover it and more than two decades later that front page remains on her wall at home, that intro of yours burned into her memory. “So much pomp,” you wrote. “A coffin on a gun carriage topped with lilies and a card that said ‘Mummy’. Postilion riders in yellow braid. Guardsmen in scarlet. A tenor bell tolling half muffled. And for once, no one — anywhere in the world — had to ask for whom the bell tolled.”

No other journalist came close. But it was your books that drew a vast new audience to your writing. True Grit, a collection of pieces about horseracing, has rarely been out of print for the past 25 years. Horses and racing were always a passion but sometimes you kept your best for the humans who followed them. You captured the trainer Bart Cummings by saying his eyebrows were “a creeper in search of a trellis”. At the memorial service for the great jockey Roy Higgins you explained his popularity by saying he was “the benign presence, he was humble, he was generous, he was courteous, he didn’t carry grudges, he didn’t look back, he wasn’t sour or cynical … He was a great human being and that might be the biggest story, because it’s harder to be a great human being.”

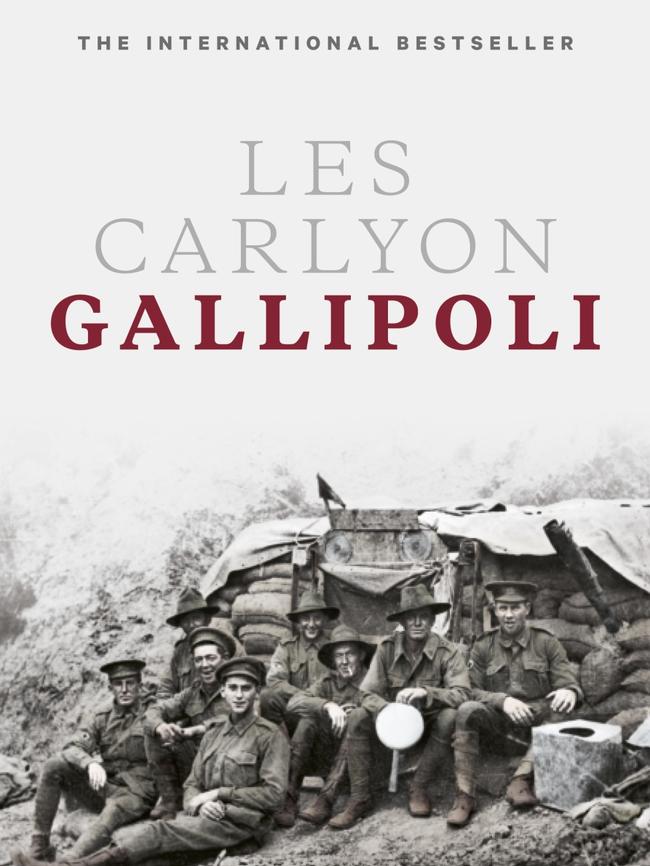

What about all those countless lovers of military history? How duped must they have felt after a lifetime of being numbed by turgid battle accounts, only to pick up copies of your Gallipoli and The Great War? You were no longer just a writer but a necromancer, bringing back the dead with such force, large chunks of myth and legend crumbled and fell off the pages. You turned and gazed out at the pockmarked Anzac Cove, its lifeless gullies and ridges “bleeding its yellow sludge into the Aegean every time the rains come. All that blood and bone from 1915, and still this place refuses to bloom.”

Beautiful words, but you never let them smother your ability to analyse complex issues and explain them simply. And so you observed how “little wars, much like tumours, sometimes turn into big wars, not because those in charge intend this to happen, but because the thing they have created develops a life of its own. It grows on them, muddling their senses and slipping into places it shouldn’t, until finally it gets away from them, so big and so painful that all they wish is for it to go away.”

You may have written about the big topics, travelling to places like Hiroshima on the 50th anniversary of the bomb being dropped, but you were never overawed by the large stage. There was always time for a wry aside. At a dawn service in Gallipoli you look on as: “The Australians murder a few slabs of beer and the New Zealanders murder a few vowels.” The mysteries of Soviet politics could be explained simply: “I don’t know much about the schemers at the Kremlin, except that they are inclined to be pasty-faced and geriatric; being half-dead has become a credential for office there.”

Your work had a touch of HL Mencken, the pithy American satirist you admired. But mostly it was pure Leslie Allen Carlyon, a man as much at ease leaning on the fence at dawn track work, yarning with small men with high-pitched voices, as he was in boardrooms rubbing shoulders with the powerful.

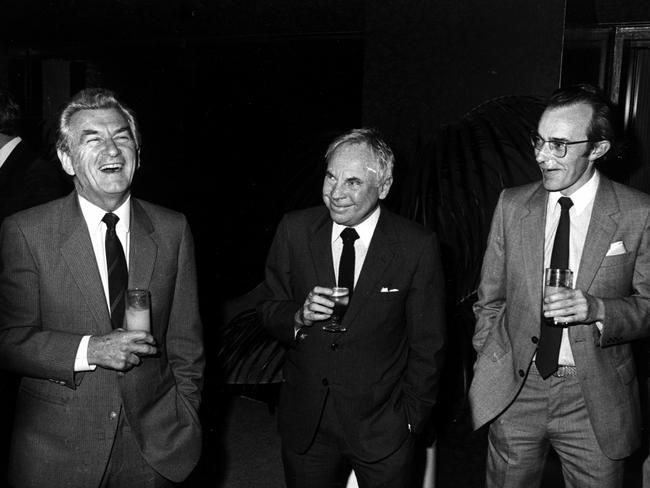

Kerry Packer was a great admirer of your work. He once invited you to lunch at his headquarters in Sydney’s Park Street. You both nibbled sparingly on small portions of fish while devouring large numbers of cigarettes. They say the fire department was on standby because so much smoke was billowing through the tiny space under the door. Over 3½ hours you spoke of horses and euthanasia and horses and politics … and horses. Packer was his usual gruff self that day, but you also detected a mellowness. A few years later you wrote that “for all the bluff manner, you sensed he was lonely, even though thousands wanted to be his friend. Maybe that was why he was lonely.”

Something you never were. You had a modesty that was maddening at times. “I just push words around the page,” you shrugged one day. But at least in recent years you never tired of boasting about your finest work — that family of three children and seven grandchildren headed by you and Denise, your wife, editor, manager and inspiring counsel for more than 50 years. And now they have lost you while the rest of us have lost one of the nation’s greatest voices.

Les, another of your journalistic heroes, the American columnist Red Smith, once wrote after the death of a colleague that we should not mourn for the dead because “This is a loss to the living, to everyone with a feeling for written English handled with respect and taste and grace.”

He could have been talking about you. Try getting a computer to write like that.

Garry Linnell has been editor of The Daily Telegraph, editor-in-chief of The Bulletin and editorial director of Fairfax. Les Carlyon taught him everything he knows.

-

A wordsmith’s life

Books

Paper Chase: The Press Under Investigation (1982)

True Grit: Tales from 40 Years on the Turf (1996)

Heroes in Our Eyes (1998)

Gallipoli (2001)

The Great War (2006)

The Master: A Personal Portrait of Bart Cummings (2011)

Positions

Editor, The Age (1975-76)

Editor-in-chief, the Herald and Weekly Times (1985-87)

Council member, Australian War Memorial (2006-19)

Awards

Walkley Award for magazine feature writing 1971

Graham Perkin Journalist of the Year Award 1993

Walkley Award for journalism leadership 2004

Melbourne Press Club Quill Award for Lifetime Achievement 2004

Prime Minister’s Prize for History 2007 (for The Great War)

Companion of the Order of Australia, Queen’s Birthday Honours List, 2014