Idea of natural talent sells hard work short in sport

ONE of the things science has taught us to be wary of appearances. Tiger Woods looks like he was born to play golf - but was he really?

ONE of the great things about science is that it has taught us to be sceptical about surface appearances. The world seems flat, but it is, in fact, round. Tiger Woods looks like he was born to play golf - but was he really?

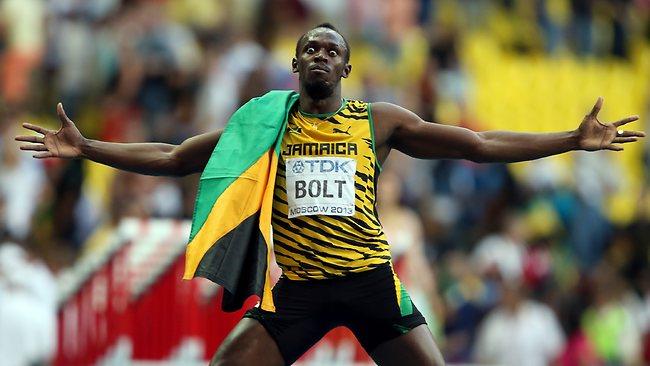

The idea that Woods was genetically predisposed to hit balls seems, on the surface, self-evident. You only have to look at the way he swings a club to realise that genius was encoded in his DNA. A similar analysis might be applied to the free-kick taking of David Beckham or the tennis playing of Roger Federer. In Bounce, my 2010 book, I challenged this view, following in the steps of authors such as Malcolm Gladwell. Much of the intellectual ballast for the book was provided by the work of Herbert Simon, a cognitive scientist who won the Nobel Prize in 1978, and Anders Ericsson, of Florida State University. According to this approach, what looks like talent is, in fact, the consequence of years of practice. Hence, the idea that 10,000 hours is what it takes to attain expertise. Woods, for example, started playing golf at the age of one, played his first pitch-and-putt round at two, and had practised many thousands of hours by the age of 10. When he became the youngest winner of the Masters in 1997 and was acclaimed by pundits as having been born with a "gift", Woods laughed. "It looks like a gift, but that is because you haven't seen the years of dedication that went into the performance," a colleague said. This is the danger of surface appearance. Recently, the debate on nature versus nurture has ignited again. The Sports Gene, a book by David Epstein, has sought to elevate the role of genetics in the analysis of success. It is well written, and many of the examples about running, jumping and other "simple" sports are uncontroversial. There is little doubt that it helps to have fast-twitch muscle fibres if you want to be a sprinter. Similarly, a long Achilles tendon is helpful if you aspire to be a high jumper. The anatomical advantages enjoyed by many top athletes in simple sports are often caused by genetic differences. But the 10,000-hour notion was supposed to apply only to complex areas of sport, and life. Take the case of reaction speed in sport. For a long time, it was thought that those, such as Federer, who could react to a serve delivered at more than 150mph, were blessed with superior genes. The idea was that Federer was born with instincts that gave him the capacity to react to a fast-moving ball, where most people would see a blur. Federer's speed is, according to this analysis, a bit like Usain Bolt's fast-twitch fibres: encoded in DNA. This turned out to be quite wrong. On standard tests of reaction, top tennis players are no faster on average than the rest of us. What they possess is not superior reactions but superior anticipation. They are able to "read" the movement of their opponent (the torso, the lower part of the arm, the orientation of the shoulders) and thus move into position earlier than non-elite players. In fact, they are able to infer where the ball is going a full tenth of a second before it has been hit. This is a complex skill encoded in the brain through years of practice; not an inherited trait. One of the reasons why practice is so important is because it transforms the neural architecture of the brain. To take one simple example, the area of the brain involved in spatial navigation - the posterior hippocampus - is much bigger in London black cab drivers than the rest of us. But, crucially, they were not born with this; it grew in direct proportion to years on the job. Proponents of talent tend to respond by saying: "Are you seriously saying that talent counts for nothing?" Well, that depends on what is meant by talent. The problem is that different notions are used interchangeably. What does it mean to say that Jonny is more talented than Jamie at, say, tennis? Does it mean that Jonny is better at the moment? Or that Jonny is improving faster? What if Jamie starts to improve faster than Jonny? Is Jamie now more talented than Jonny? In many fields, it has been found that those who start off below average (who might be said to lack talent) improve, over time, faster than average. In others, those who start out learning faster continue to accelerate. In one study of American pianists, those who would go on to achieve greatness were not standing out from their peers even when they had been studying intensively for six years. At what point do we decide who is talented? After a week, a month, ten years? The answer may be different depending on the time-span chosen, not to mention the level of motivation and the quality of coaching brought to each hour of practice. In the studies cited by Epstein, these variables are rarely taken into account. What this shows, I think, is that a simple notion of talent (which still rules much of the world) is misleading. Complex skills are not hardwired like height, and neither is the disposition to learn. Many of the differences in the world today when it comes to sporting prowess are determined not by genetic differences, but by differences in the quality of practice. Brazil once had the top team in football because of highly efficient training techniques. Instead of learning from them, English coaches, obsessed with talent, said: "Brazilians are born with superlative skill; our players could never do that". The consequence was that we didn't teach technical competence to our youngsters. Our 11-year-olds continued to play on full-size pitches, hoofing the ball up to the front man, and touching the ball infrequently. No wonder we went backwards. Spain superseded Brazil because they found a way of accelerating skill-acquisition beyond their competitors. I would have no problem with the notion of talent if it was amended to incorporate the complexity in human performance. The problem with the simplistic notion prevalent today is that it can destroy resilience, as many studies have shown. After all, if you are struggling with an activity, doesn't that mean you lack talent? Shouldn't you give up and try something else? It is worth remembering that SF, a famous volunteer from memory literature, went from below average to world-class level in memory skill with two years of training. Was he talented? Ultimately, it depends on how you conceive of talent. What is clear is that the present notion is deeply misleading. The power of practice, on the other hand, remains vastly underrated. The Times