Cities choking on ageing road infrastructure ‘no longer coping’

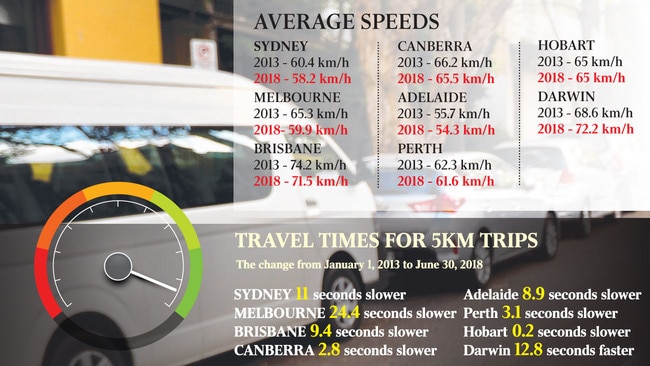

Average driving speeds haven’t just slowed in Sydney and Melbourne. Every capital city except one reported longer travel times.

Average driving speeds across Australia’s capital cities have slowed by up to 8 per cent since 2013 and road infrastructure is “no longer coping” with increasing urban congestion and population growth, a new report from the nation’s peak motoring body states.

The report, published today by the Australian Automobile Association, finds most capital cities are stretched beyond their capacity, which contradicts the solution put last week by Minister for Cities, Urban Infrastructure and Population Alan Tudge that settling new migrants in capital cities other than Sydney and Melbourne will help ease urban congestion.

Every city except Darwin reported slower travel times and lower average speeds, according to the data, which was collected at 15-minute intervals on roads across all capital cities between January 2013 and June this year.

The report shows congestion has increased significantly and average speeds have become far more variable, making travel times longer and less predictable.

Speeds in Sydney and Brisbane fell by 3.6 per cent and 3.7 per cent and in Melbourne the slowdown was 8.2 per cent — with the average speed decreasing from 65.3km/h to 59.9km/h.

Speeds on capital city airport routes have decreased by 6.1 per cent on average since 2013, with the most congested route — from Melbourne’s Tullamarine into the CBD — taking five minutes longer than five years ago.

The Dandenong route to the Melbourne CBD has reported the greatest increase to average trip times of any city route nationally, adding an additional 3.7 minutes to the trip over the five year period.

The report says land transport congestion costs, $16.5 billion in 2015, may reach $37.3bn by 2030.

AAA chief executive Michael Bradley said the findings reflected a national transport system “no longer coping”. “No one benefits from congestion and everyone pays,” Mr Bradley said.

“This report confirms what most people living in our major cities know all too well. But we hope it also helps stimulate discussion and problem-solving so Australia can develop smart measures to address our worsening congestion. There is no quick fix but more of the same is not the answer, given our tax system contains well-known problems and the federal budget has the proportion of taxes being reinvested into infrastructure forecast to decline significantly in the next three years.”

Over the next four years, the proportion of net fuel excise returned to infrastructure is projected to decline to 32 per cent, compared to the average 50.5 per cent over the past decade.

Celeste Burke, 22, drives from the Sydney inner-city suburb of Redfern to Macquarie Park in the city’s north every day and opts to leave significantly earlier to avoid morning peak-hour traffic.

“When I was trying to find a gym, I figured it would be better to join one closer to work so I can definitely avoid the horrible morning traffic,” Ms Burke said.

Her route has recently been affected by the closure of the train line between Epping and Chatswood, which has displaced about 20,000 commuters.

Travellers can use one of 120 new buses introduced to help mitigate peak-hour congestion, but Ms Burke said this only worsens traffic by increasing the number of vehicles on the road. Since the train line closed, her commute home is at least 10 minutes slower.

From Brisbane originally, Ms Burke said the difference in city planning between the Queensland capital and Sydney was stark.

“In Brisbane the traffic is quite confined to the motorway and freeway, but what I’ve noticed in Sydney is that it’s everywhere,” Ms Burke said.

‘‘In Sydney a lot of the toll roads are essentially just as busy, if not busier, than other roads.”