Bill Shorten’s tax grab to affect the lowest incomes

More than 610,000 Australians on the lowest incomes stand to lose an average of $1200 a year under Bill Shorten’s proposed reforms.

More than 610,000 Australians on the lowest annual incomes stand to lose an average of $1200 a year in tax refunds under Bill Shorten’s proposal to abolish cash rebates for tax credits on shares held by retirees, investors and ordinary taxpayers.

The Australian can reveal that Treasury analysis of official tax data figures shows the largest group of people to be hit by Labor’s $59 billion tax grab will be those receiving annual incomes of less than $18,200, the majority of whom receive the Age Pension.

The government responded by accusing Labor of stealing from pensioners and retirees in what it declared was a “brutal and cruel” tax grab aimed at funding the Opposition Leader’s “reckless spending” agenda.

In a further blow to Labor’s claims that the scrapping of the refund scheme would hit only the wealthy, the Treasury analysis reveals that only 5000 individuals on incomes of more than $180,000 a year will lose the cash refunds for excess tax credits.

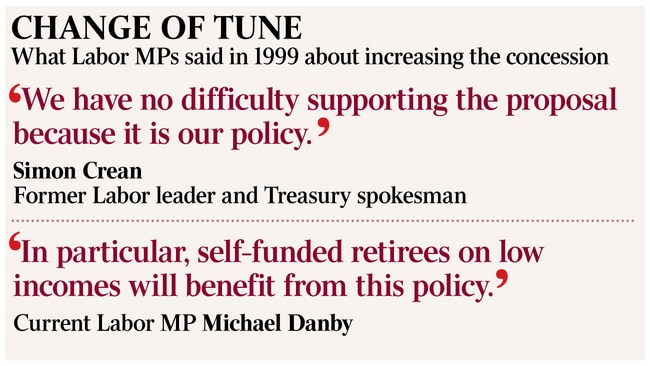

Former treasurer Peter Costello, the architect of the refund system in 2001, attacked the plan, claiming it would hit low-income earners and risk upending two decades of bipartisan tax policy.

“This will affect millions of retirees, age pensioners and part pensioners — this is a tax rise for them,” Mr Costello said.

GRAPHIC: What Labor’s tax proposal means

The total hit to people on salaries under $87,000 is estimated to be $2.2bn, or about 86 per cent of the total paid out to individuals eligible for a cash refund from the ATO when claiming imputation credits that exceed their annual tax liabilities.

The loss of income averaged over the total pool paid to about one million individuals was estimated to range from an average of $1200 a year up to $5000.

The total number of people estimated to be affected could be as high as 1.5 million, with about 550,000 members of self-managed super funds also at risk of losing a median income stream of up to $5000 a year.

Labor, scrambling to defend the policy after Mr Shorten unveiled the plan in a speech to the Chifley Institute in Sydney, claimed it would return $59bn to the budget over 10 years and hit only wealthy individuals and self-managed super funds. Mr Shorten flagged the prospect of using the additional revenue to pass on further “tax relief” for low and middle-income earners and linked the measure to a new multi-billion-dollar scheme allowing businesses to deduct 20 per cent of their investment in assets over $20,000 from July 2020. Branded the Australian Investment Guarantee, the scheme is estimated to cost $10.3bn over the decade.

“What we’re doing is we’re clearing the decks to make sure that we have a stronger budget position, to make sure that we can fund our schools and hospitals, and to make sure that we can offer tax relief for low and middle-income Australians,” Mr Shorten said.

Opposition Treasury spokesman Chris Bowen said the cost of refunding the dividend imputation credits had become unsustainable, ballooning out from $550 million in the 2001 budget — when the measure was introduced — to more than $6bn a year.

“It costs now $6bn a year and is projected to rise to more than $8bn a year, more than the commonwealth government spends on public schools or on childcare,” Mr Bowen said. “That’s why David Murray found in the Financial Systems Inquiry that it was a very significant fiscal drag.”

The plan came under attack from the super industry, pensioner groups and the government, which claimed that in addition to low-income individuals who stood to lose, 3.5 million superannuation fund accounts could also be hit.

Financial Services Council chief executive Sally Loane warned that “constantly changing the rules and hitting retirees hardest will only undermine the purpose of superannuation, leaving more people reliant on a taxpayer-funded retirement”.

Her warning was supported by Self-Managed Super Fund Association chief executive John Maroney, who warned it could lead to a “shift in superannuation fund investment strategies”.

“Funds seeking yield to deliver retirement income, especially SMSFs which are paying income streams, would need to shift their asset allocation towards investments which can provide increased yield,” he said. “This may lead to funds having to shift to a higher risk asset allocation in the retirement phase.”

With the Turnbull government still feeling the effects of an electoral backlash to its own tax changes to superannuation two years ago, Scott Morrison framed a pre-budget attack on Labor as wanting to impose a tax rise on millions of Australians while raiding their pension funds.

“This is a tax smack on more than a million Australians, including 230,000 pensioners,” the Treasurer told The Australian.

He lashed the Labor policy on equity grounds, warning it would allow the well-off to continue to realise the value of their franking credits fully while disadvantaging those who paid little or no tax.

“For those on low incomes, they get a refund when their tax rate is set at a level which means they didn’t get the full value of those credits, and it goes back to that fundamental fairness point — why should you and I get the full value of a franking credit and a part pensioner does not?” he told Sky News.

Revenue Minister Kelly O’Dwyer said the Treasury analysis of official tax office data “revealed that the true impact will be on retirees and pensions with modest retirement incomes, not high-income earners”.

The Treasury analysis obtained by The Australian shows the largest group to be affected are the 610,000 people on incomes of less than $18,200 a year. This group represented $500m in total refunds. On average they stood to lose $1200 a year.

The second largest group to be impacted are those on annual taxable incomes of between $18,201 and $37,000, of which there are 360,000 who receive franking credit refunds. This amounted to $800m a year in refunds, or an average of $2200 a year

A further 120,000 will lose $600m worth of refunds, based on taxable incomes of between $37,001 and $87,000, with some losing up to $5000 a year in income.

Only 5000 people on incomes of $180,000 or higher would be affected, representing just $100m paid out by the ATO.

A further 30,000 on taxable incomes of between $97,001 and $180,000 a year would lose $200m in refunds.