The story of East African crime in Melbourne

Crime by youths of African background has been a contested topic in Melbourne. Statistics tell the story.

East African crime in Melbourne

One day, Melbourne had no African crime gangs. It was all media-driven hysteria. Seemingly the next day, authorities said there were indeed gangs but only 150-odd miscreants, nothing to become too alarmed about.

Where is the truth to be found?

Crime with an African face has been a bitterly contested topic in the lead up to Saturday’s Victorian election. It’s not news that Sudanese-Australians are over-represented in crime figures but until now, the spread and scale of the problem has not been put clearly on the map.

-

Hotspots

This map shows clusters of offenders born in the Horn of Africa countries of Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia and Sudan. Those clusters form an arc around the centre of the city.

Nineteen local government areas stand out. Each has more than 250 African-born offender incidents and makes up more than 0.5 per cent of total incidents over the past decade. Even at their worst, the African crime numbers are slight compared to law-breaking by the Australian-born but the African record is more significant than you’d expect, given their small population in Melbourne.

The map uses “alleged offender incident” data from July 2008 to 30 June 2018 supplied by Victoria’s crime statistics agency. This measure of crime is linked to the nationality of offenders (when police take the trouble to record it). A hotspot is a Local Government Area at the high end of the range for the number of African offender incidents in the top 10 nationalities and their share of total incidents. The absolute number of incidents is still low.

An incident involves one or more offences tied to a single offender, although the same offender may recur in the data linked to multiple incidents.

This article often uses the short-hand “offenders” but the count represents incidents. The same goes for the term African, which here means people born in the Horn of Africa countries.

The original data covers the top 10 nationalities responsible for crime and dealt with by police in each of Victoria’s 79 LGAs.

African offender numbers over the past 10 years were added together, followed by calculation of their percentage share of total offenders (not just the top 10). Year-to-year changes in a given LGA involve small numbers.

-

Law and order politics

This map shows why the African crime problem is overwhelmingly an issue for Labor. The top LGA crime spots map on to 31 ALP seats, including the four vulnerable bayside districts of Frankston (margin 0.5 per cent), Carrum (0.7), Bentleigh (0.8) and Mordialloc (2.1). Victoria’s lower house has 88 districts.

Bill Shorten’s federal seat of Maribyrnong in the city’s northwest overlaps with the LGA of the same name, which has the biggest share of African-born crime in relation to total crime. Premier Daniel Andrews’ own district of Mulgrave, in the east, intersects with the LGA that has the second-highest share of African crime.

-

A closer look at lower house crime

The five worst LGAs match up with 13 Labor seats and two held by the Greens.

In some districts, only a small area overlaps with the LGA hotspot, and crime may be at too low a level to become a political issue. Even where a district falls squarely within an LGA hotspot the absolute number of African-born offenders is typically small.

Some of the African crime hotspots with bigger numbers overlap with seats that are rock solid for the ALP, such as Footscray (14.6 per cent) and Dandenong (12.9 per cent). There may be less pressure here for a Labor government (or an incoming Coalition administration) to fix the problem.

Even at their highest, African crime totals are dramatically lower than those for the Australian-born. That may be no consolation for victims traumatised by brutal attacks or for their neighbours who now live in fear.

It’s also true that the fixation with African crime is hurtful for the law-abiding majority of these communities, who stand out in a city like Melbourne. With their black skin, it’s hard for them to seek the cover of anonymity in a crowd. It’s not a straightforward racialised issue. Some victims are fellow Africans, some who run in gangs with blacks are white, Middle Eastern or Pacific Islanders.

-

African crime on the rise

The number of African-born offender incidents rose by 209 per cent over the decade to 2017-18. This outstripped their combined population, which increased by 57 per cent from the 2006 census to 2016 (the time periods do not match up exactly). Over that period there may have been more offenders responsible for multiple incidents, although the government says youth recidivism is down in the latest figures.

The Sudanese-Australian share of total statewide offender incidents went from 0.8 per cent to 1.4 per cent over the decade. They make up 0.13 per cent of Victoria’s population. The Sudanese population grew to 8415 in 2016, 35.5 per cent up from 2006.

The combined 2017-18 African total of offender incidents was still small (3384) compared to the Australian-born figure (135,046). Those Australian offender numbers grew by 45.9 per cent during the last decade, while their population count lifted by only 12 per cent (2006-2016). On these figures, it looks like crime in Victoria has been getting worse, especially with African-born offenders.

But “alleged offender incidents” are not the only measure.

Earlier this year Victorian Police Minister Lisa Neville said African youth offending had reached “a new level” in 2016, prompting the government to strengthen frontline law enforcement. The per capita criminal incident rate fell 7.8 per cent last financial year. Criminal incidents include offences in which the police have not identified a suspect. Yesterday Ms Neville’s office said youth offending incidents were down 5.9 per cent last financial year.

-

Crime in context

The red column shows the percentage share of top 10 African offender incidents in the total offender count for each of the 19 LGA hotspots. The blue column gives the African share of local population and serves as a measure of their over-representation in the crime data.

We don’t have complete figures showing all the nationalities involved in crime in each LGA. They are not published because the small numbers raise privacy issues.

-

Long list of councils with African crime

This includes LGAs that fall below the hotspot cutoff of 250-plus African-born offender incidents making up more than 0.5 per cent of total offenders. Running down the ranking, you can see that offender numbers quickly get very small and 33 of Victoria’s 79 LGAs had no African offenders in the top 10 at any time over the past decade.

-

The Top Five

This table offers a sharper focus on LGA crime hotspots with Sudanese offenders, the biggest of the four African groups in Melbourne and the one most commonly cited in media reports. Here, you can see the LGAs where Sudan was in the top 5 crime nationalities over the past five years. The top two positions typically go to “Australia” and birth country “not specified”.

In LGAs such as Mooney Valley and Melbourne, the Sudanese count is significant, whereas in Colac-Otway or Swan Hill, the Sudanese make the top five even when offender numbers are quite small. In some councils, such as Golden Plains, the only data is for Australian-born and birth country “not specified”.

-

Why the data may understate the African crime problem

Crimes where the police have not identified an offender are not included. Some residents in African crime hotspots have complained police seemed reluctant to make arrests. An offender incident may involve multiple offences and victims.

In many cases, police did not record any nationality at all and some of these offenders may have been from the Horn of Africa.

Australian-born offenders from an African background are not included. Victoria Police chief commissioner Graham Ashton has said the African crime problem involved “mostly people born here”.

Offenders with family from Horn of Africa countries but born in refugee camps in Kenya are not counted. Kenya is often considered part of the Greater Horn of Africa and it is home to some of the world’s biggest refugee camps. Kenya accounts for 419 offender incidents 2008-2018.

Offenders of white, Middle Eastern or Pacific Island appearance who have taken part in gang activity with Africans are not counted.

Data does not capture the trauma suffered by victims or the fear amplified in a community. It may be not so much the number of incidents but their nature. Media reports highlight lone victims beaten by a pack of youths who show no pity, brazen home invasions, robberies with casual violence and displays of utter contempt for police authority.

-

Why the figures may exaggerate the problem

The incidents recorded cover the full gamut of dealings with police, including a caution or official warning, and less serious law-breaking as well as notorious incidents of the kind given media coverage.

Over the past five years, “crimes against the person” as a principal offence have increased their share of alleged offender incidents, while the most common offences are to do with property and deception.

It’s already been acknowledged that offenders from Sudan/South Sudan are over-represented in statewide crime figures for aggravated robberies, assaults and aggravated burglaries.

With black skin, young Africans stand out on the streets and it’s possible police may be more likely to target them.

Top 10 nationality data for LGAs gives an impression of the scale and trend of African crime across Melbourne but no more than that. In some LGAs in a given year, it doesn’t take many offenders at all to make the top 10 list and even where there are many nationalities the count can still be small.

In some LGAs, such as Maribyrnong, the gap between the African crime rate and population share may be narrowed by non-resident Africans who come into the area. This would not be much of a factor in places, such as Greater Dandenong, with significant African population.

There is likely to be some double counting of serial offenders in the incident data, hence the inclusion of African offenders as a percentage share of total (not just top 10) offenders. Victoria Police have blamed a core group of 150 Australian-Africans accounts for much of the problem.

In 2017-18, there were 873 “unique offenders” born in Sudan, making up 1.1 per cent of the total.

Police Minister Neville said yesterday that “high-harm crimes by African youth offenders” had fallen in the latest figures. “We’re delivering an unprecedented investment into 3,135 new police, and giving police the powers, resources and tools they need to keep the community safe.”

Victoria’s Sudanese population is young, with many in the peak age bracket for offending. Many are unemployed, have patchy education and come from broken families with diminished parental authority.

Data cannot show the hurt felt by law-abiding African-Australians viewed with suspicion and hostility when going about normal life in public.

-

Tracking African crime

This chart shows the number of LGAs with African crime in the top 10 nationalities over the past decade. Sudanese account for the lion’s share.

-

Why focus on the Horn of Africa?

The Horn of Africa region — embracing Sudan, South Sudan, Somalia, Ethiopia and Eritrea — has a history marked by colonial invasion, the struggle for independence, great power intervention, civil war, separatist rebellion, coups, military rule, border disputes, fights over scarce resources, child soldiers, millions of refugees and displaced people, mass slaughter, police corruption and brutality, state collapse, jihadist militias, warlordism, drought, famine and communal violence.

The news is not all bad. Only this month the leaders of Ethiopia, Eritrea and Somalia met to promote regional stability and economic integration. In September, a peace deal was struck in South Sudan’s five-year civil war, although previous agreements have not lasted long.

Nobody suggests a racial link to crime in Melbourne but there is a question whether the horrors that qualify people for refugee status also create problems for their resettlement in a peaceful society ruled by law, especially if those new arrivals encounter prejudice and unemployment.

Most East Africans make a difficult transition successfully and some individuals — such as child soldier turned Sydney lawyer Deng Thiak Adut — break free from the past in a way that inspires admiration and hope. It’s also notable that the smaller local group from Eritrea, which has not been spared the violence and misery of the Horn of Africa, hardly figures in the top 10 crime data. And although the Ethiopians are the second largest local community — their numbers in Victoria more than doubled between 2006 and 2016 — their offending falls well below that of Sudanese. Is it that the Sudanese are more recent escapees from horrors that still have a grip on their homeland?

South Sudanese first appear in our 2011 census, two years before their new nation would descend into the latest civil war in the Horn of Africa. But some African parents of children born here insist their offspring have to be judged as products of the Australian experience, not the conflict-ravaged home country.

-

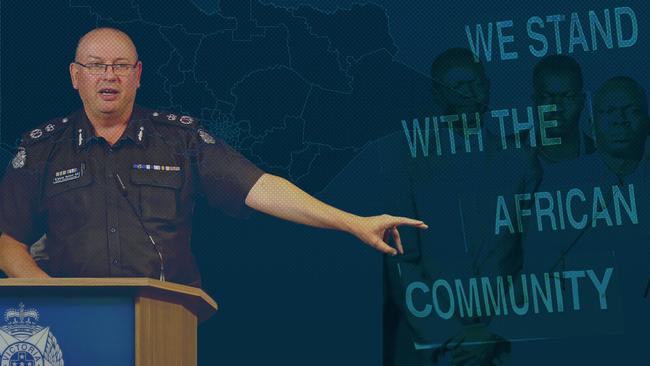

The psychology of crime debate

Victoria’s authorities have sent the public mixed messages — at first there were no gangs, then they appeared in policespeak disguise as “networked criminal offenders”, next the media were told that, yes, there were gangs but most of the mischief in the headlines was the work of a small core group of 150. There has been one constant message: Melbourne is one of the safest cities in the world and overall crime is on the way down. But that abstract reality doesn’t translate to the lives of victims scarred by terrifying attacks or neighbourhoods with significant crime clusters.

Many in Melbourne would have remembered the 2007 precursor to all this, when Liberal immigration minister Kevin Andrews cut back the African refugee intake, citing crime and other symptoms of poor integration. Queensland’s premier Anna Bligh denounced his rationale as “a pure form of racism” — something not obvious in what he actually said. Ms Bligh said Africans were not over-represented in the figures she saw (this year police in the Queensland city of Toowoomba reported the same conclusion). In 2007, Victoria’s police commissioner Christine Nixon contradicted Mr Andrews, insisting the Sudanese were “not, in a sense, represented more than the proportion of them in the population”. If true then, it was not true for long. Nobody today disputes the fact of Sudanese over-representation in crime, although exculpatory factors such as their young age are invoked by criminologists.

Back in 2007, as now, Victoria’s authorities have not wanted people alarmed by crime that in absolute numbers is arguably trivial, especially when there is a risk of stigmatising a highly visible community some of whose members may already be struggling with resettlement in a strange land. A less noble motive may have been to cover up the failure of government, police and the African community to detect and deal with real problems early enough.

There’s likely to be more than one reason for the erratic statements made by authorities but the risk remains the same: that people in Melbourne lose trust and become more polarised over the issue. If political and police leaders do manage to strike the right balance between candour and reassurance, they may find the public disposed to believe that whatever the official account is, the reality must be worse. That outcome would be bad for everyone, including African-Australians. The stigma deepens. And until the people of Melbourne feel safe, it’s likely to be hard to engage their interest and support for the kind of social programs said to be necessary to address the problems underlying African crime.

In a climate of fear, it’s difficult to focus attention on to whether or not there are lessons to be learned — for all three levels of government — in the violent troubles involving an East African minority in Melbourne. And uncomfortable as the media coverage can be, there may also be insights and a stimulus to action for Horn of Africa communities in Australia.

Federal Liberal Party ministers Peter Dutton and Alan Tudge have asserted it is strictly a law and order question for Victoria, claiming neither NSW nor Queensland has the same problem. It’s true that African crime features little as a media topic today in those states.

In the Sydney suburb of Bankstown, home to a Sudanese-Australian community, problems with African gangs are almost non-existent, according to NSW Police Chief Inspector Bob Fitzgerald. “We do have problems (similar to those seen in Melbourne) on occasion, but they are nowhere near as frequent as people suggest,” he told news.com.au in July. “And, when these things do happen, we find they are carried out by people from a range of backgrounds from Filipinos, Anglos, islanders … people from all over the world. We don’t have mass gangs roaming the street. You might see groups of Sudanese people on the street, but you’ll see people of lots of different cultures hanging together as well.”

But African crime has been a sporadic media focus in Brisbane and Sydney going back some years and although police in both cities sometimes record the nationality of offenders, the government does not publish this data. (Some criminologists appear hesitant when discussing country of birth data and crime, as if it cannot be done without unleashing racism.)

Victoria has a big Sudanese community but the state represents only a third of the national population. Asked about the evidence that all is well in NSW and Queensland, neither Mr Dutton nor Mr Tudge offered an answer. Nor did Mr Dutton’s office have anything to say in response to The Australian’s question whether or not the Commonwealth had learned anything from the African experience that might improve resettlement and integration of refugees. It’s not a trivial issue. Australia has just settled a special intake of 12,000 refugees from Syria and Iraq. Our humanitarian program — one of the most generous, per capita, in the world — expands to 18,750 places this financial year. These are gestures of hope, like planting a tree that will grow beyond a human lifetime. How much do we care to know about the seed and the soil?

MORE: What people are saying

MORE: African crime hits Labor seats

Know about some overlooked data that tells an important story? Email DataDive@theaustralian.com.au