THE government's claim that it will provide permanent compensation to 70 per cent of households for its carbon tax is based on a false premise: that the Australian government will receive the revenues from the tax and of permit sales in the subsequent emissions trading scheme.

But Treasury's modelling of the carbon pollution reduction scheme found that by 2050 nearly 50 per cent of permits would be imported, even with the 2020 target set at a 5 per cent reduction in emissions below 2000 levels. Were the target a 25 to 30 per cent fall in emissions, the share of imported permits would exceed 60 per cent.

When permits are bought overseas, domestic prices still rise, as the purchases add to Australian costs of production.

With the carbon tax increasing at 4 per cent a year in real terms, ensuring households are no worse off requires corresponding increases in commonwealth outlays. But with foreign sellers of permits getting more and more of the revenue, there is a mounting gap between the scheme's costs and the government's income.

The sums involved are hardly trivial. Even in the 5 per cent reduction scenario, by 2050, annual imports of permits amount to $23 billion at today's prices; that is, each man, woman and child in this country will be transferring $600 a year to foreign owners of permits. Whatever one may think of those transfers, they mean the government's compensation promise is vastly underfunded.

Moreover, that funding gap worsens steadily over time as the number of permits shrinks and the share of them purchased overseas rises. And the more successful the scheme is in reducing emissions, the sooner the problems of funding compensation will emerge.

Treasury's CPRS modelling assumed the rest of the world, including our major competitors, implemented a similar scheme. That made possible large-scale international trade in permits, lowering the cost of emissions reduction. Even then, the government's promise could not be funded.

However, it is now clear that there is little prospect, if any, of global agreement, and that our major competitors have no intention of undermining their resource exports. So we will be going it alone. And that makes it even less likely the government can meet its promise.

This is because a unilateral carbon tax must cause costs to rise and incomes to fall.

That reduction in real incomes will be especially great in an economy whose comparative advantage lies in carbon-intensive production. With a low starting price, the impacts take time to eventuate; but as they do, two or more dollars of national income could be lost for each dollar raised in carbon tax revenues. And that loss will rise steeply as the carbon price increases.

If full employment is to be maintained, that loss must reduce real wages. Ensuring households are no worse off therefore requires compensating them both for higher prices of carbon-intensive goods and for lower earnings.

With the resulting losses a multiple of the scheme's revenues, those revenues could not possibly fund the compensation needed. In practice, the losses are likely to be even higher than two dollars in costs for each dollar of revenue. This is because the government's scheme introduces myriad inefficiencies.

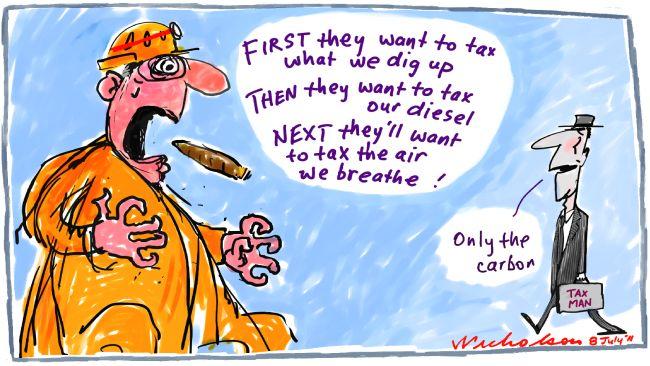

For example, the carbon tax will be paid only by the 500 largest emitters; producers that compete with these firms for inputs and for customers, but fall below the emissions threshold, will be exempted.

As a result, exempted producers will expand while taxed producers contract, even though the former are less efficient than the latter.

And those distortions will be aggravated if a new tax on fuel hits some firms but not others.

Yet further losses in productivity and hence earnings arise from the interaction between the proposed compensation and the income tax system.

A carbon tax increases prices relative to wages. As the Ross Garnaut report acknowledges, that reduces incentives to work, which are already blunted by the income tax.

With reduced work incentives lowering labour supply, earnings and hence tax payments, the carbon tax worsens the income tax's economic cost while diminishing the revenue it raises.

That is bad enough. But by focusing its compensation payouts on lower-income earners, the government will raise effective marginal tax rates.

This is because taxpayers whose incomes rise will lose compensation they would otherwise have obtained. And to make matters worse, those effective marginal rates will increase steadily over time, as high-income earners bear the full brunt of annual carbon price rises while low-income earners are shielded from them. As ever higher marginal tax rates undermine incentives to work and save, it is real wages that will suffer.

Then there are the concessions to the Greens. Locking in the grossly inefficient renewable energy targets is foolish; superimposing a carbon tax on those targets turns up the volume on a faulty amplifier, increasing the distortion. And a massive new slush fund for renewables will further damage national income, throwing resources at projects whose benefits are less than their costs.

All these measures make households worse off while reducing the revenues available for compensation, increasing the funding shortfall. But they were simply ignored in the CPRS modelling. Having assumed a global agreement, it never costed a unilateral carbon tax.

The distortions due to taxing some firms but not others were also assumed away. And it took no account of the need to fund compensation promises.

This time, that cannot be good enough.

The acid test on Sunday will be whether the government is upfront: about the income loss caused by a unilateral carbon tax riddled with discriminatory inclusions and exclusions; about how, despite that loss, it intends to finance its pledge that 70 per cent of households will never be worse off than they would have been without the tax; and about how much worse off the remaining 30 per cent will be.

That may be asking too much. For the government knows the community has no stomach for the costs its tax will impose. No wonder it has abandoned the politics of conviction for those of make-believe. And no wonder it is poised to promise compensation it has no way of providing.