Innovation key to keeping manufacturing onshore

THE future can still be bright if the nation learns to focus on value-adding, not metal-banging.

AT Redarc Electronics in Adelaide's south, software engineers peer over computer chipboards as they search for the next breakthrough in battery management technology.

Laboratory coats and glass walls define this factory. It is clean, bright and modern.

"It is the factory of the future," Redarc chief executive Anthony Kittel says. "We reinvest in new equipment every three to five years and throw out the old equipment because the technology is moving so quickly."

During the past decade, manufacturing across Australia has taken a battering. Its share of gross domestic product has slumped from 14 per cent to 8 per cent. One in every 10 manufacturing jobs has disappeared in the past five years.

Yet, against this grim backdrop, Redarc has recorded year-on-year growth averaging 25 per cent and doubled its size in the past three years. In 1997, Kittel employed just eight people; now he employs 102 highly skilled workers.

Kittel says there is no mystery to the company's success. "To buck the trend in the downturn of manufacturing, we are investing a minimum of 15 per cent of our revenue back into research and development each and every year," he tells Inquirer. "Innovation drives our company's bottom line. Not everything is successful, but that is part of groundbreaking research and having new ideas - some will fail, but then you will get some really super-successful ones.

"If you are just competing on cost, you will definitely lose; if that is the approach you take, then your manufacturing plant in Australia is destined to move offshore or close."

Being one of Australia's innovators puts Redarc in the minority of manufacturers in Australia. Most of the country's producers are in the business of high-volume, low-value-added production.

"They are banging metal, they operate as a local player in an area where they have been doing something for somebody ... in a regional monopoly," says Goran Roos, a world expert in innovation management. "Australia is overwhelmingly a commodity-based, low-value-adding producer."

Last year the Manufacturing Taskforce found the nation's hi-tech sector made up "a relatively small proportion of manufacturing" and was focused on niche markets. But high-precision, high-value-add products are growing in importance. Aerospace components, machine tools, medical devices, electronics, scientific instruments and pharmaceuticals are where Australia will succeed as a competitive global manufacturer. These areas are replacing job losses in "metal-banging".

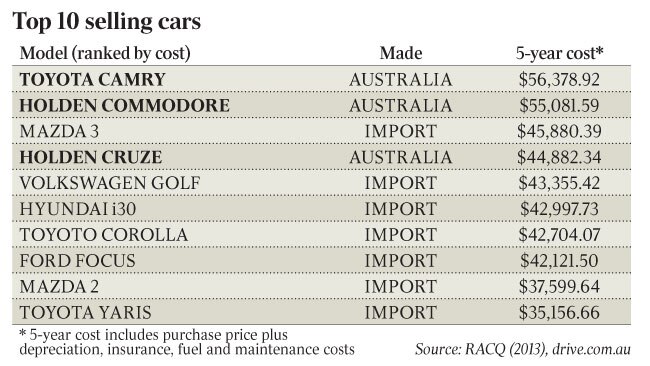

"I think the future for advanced manufacturing is exceedingly bright," says Bruce Grey, head of the country's Advanced Manufacturing Co-operative Research Centre. "Do we need the car industry? I think the answer to that is no, we don't. The billions that we have poured into the car industry ... worked for the first 10 years but they haven't worked since then. It is good money after bad now."

Grey, formerly managing director of auto parts manufacturer Bishop, says the country needs to shift its focus to developing medical technology and commercialising the rich intellectual property of research institutions.

"We have got 40 medical research institutes (in Australia) and probably a third of those are the best in the world in the fields they are operating in, but they are not producing enough in terms of tangible products and processes."

Roos, who has advised the federal and South Australian governments on advanced manufacturing strategy, says if Holden's carmaking plant in northern Adelaide closes it will not mark the end of manufacturing in Australia.

But he says there needs to be a cultural shift that recognises the nation's strategic advantage is no longer as a low-cost competitor. "The purpose of doing advanced manufacturing is to make something nobody else makes, and at that point you no longer compete on cost, you compete on value for money, and that is a fundamental distinction," Roos says.

"There is a manufacturing sweet spot for Australia, which is low-volume, high-variability, medium-high complexity, and high-value-added. That is what we are very good at. You can't go to China and find those ... companies because they are about scale."

But Roos says of the 50,000 manufacturing businesses here, only about 1500 to 2000 are globally competitive in these areas.

It is a startling statistic that people such as Brad Dunstan, at the Victorian Centre for Advanced Materials Manufacturing, is attempting to improve.

Dunstan says he is an "avid" supporter of the car industry in Australia but agrees the future of advanced manufacturing lies elsewhere. "What makes the difference and makes you capable of surviving in the global industry is intellectual property," he says.

"Our universities are world-class: they are good at doing science, they are good at technology and our companies are good at producing things, (but) there is a gap in the middle."

He foresees a bright future for the country's manufacturers, who increasingly will be producing intellectual property to be exported around the world and produced in local markets.

But he also warns that Australian businesses need to be better at change management and to recognise the need to adapt.

"I travel quite a lot promoting Australian technologies internationally, and what I see in German companies, for example, is a willingness to transform their businesses very, very quickly," he says.

"They will give up a process and say, 'China makes those bolts better and cheaper than us, so we will give that up', whereas Australian manufacturers tend to pull the goggles down over their eyes and say, 'I'm going to ride this in because I think there's a 10 per cent chance that I can pull out before I hit the ground' ... We need to change that."

Government figures show that while decline is projected for many manufacturing segments - led by 14,300 job losses in the automotive industry during the next five years - manufacturing will still grow by 7.2 per cent by 2016.

Donald McGurk, managing director of advanced electronics company Codan, believes companies can "innovate their way out of trouble". But he says there needs to be government help to educate businesses to transition to being globally competitive. "We need to give people the tools to fish, rather than giving them fish, which is what protectionism does."