Chris Corrigan reflects on 20th anniversary of waterfront dispute with MUA

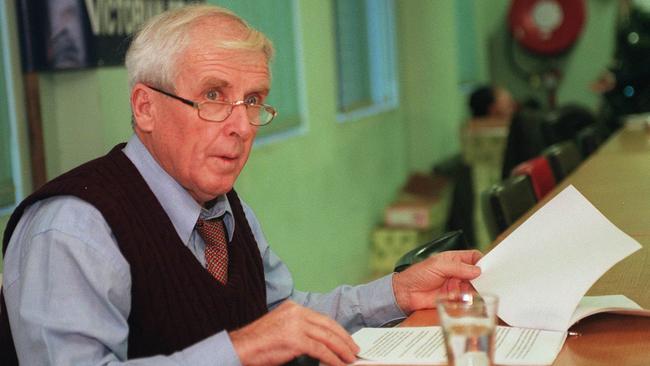

Former Patrick chief Chris Corrigan reflects on the 20th anniversary of his battle with the MUA and warns of the return of mega-unions.

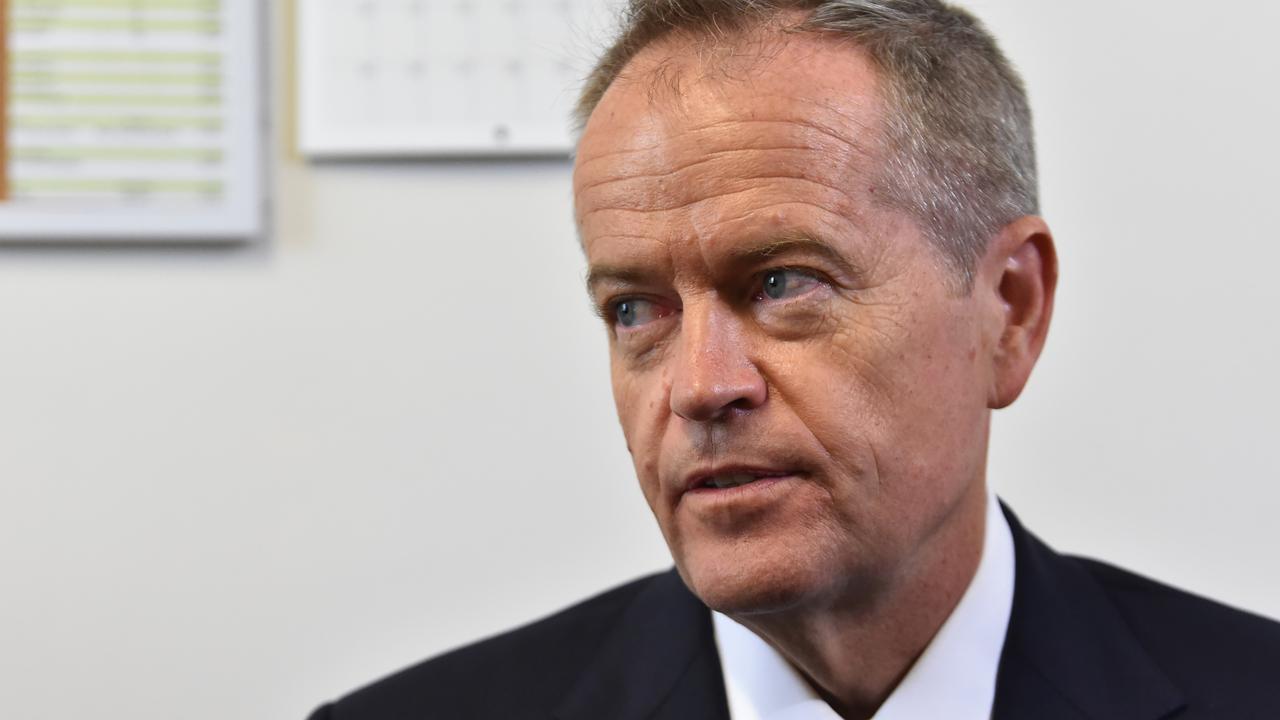

John Howard has urged the Turnbull government to revive plans to subject union mergers to a public interest test, expressing concern that the merger of the militant construction and maritime unions represented “ultra-concentration of union power”.

The former prime minister’s concern was shared by former Patrick chief Chris Corrigan, who said the CFMEU had a record of being “fairly lawless”.

“The fact that they control so much of the critical infrastructure of the country and behave in a lawless fashion, I just don’t see that as something positive from the point of view of the country,’’ Mr Corrigan told The Australian in an interview to mark the 20th anniversary of the polarising 1998 waterfront dispute.

Tomorrow in The Weekend Australian: An Inquirer special on the war on the waterfront

The Turnbull government last week abandoned plans to subject union mergers to a public interest test after failing to secure support from the Senate crossbench.

Employers have sharply criticised the decision by Workplace Relations Minister Craig Laundy not to proceed with the Ensuring Integrity Bill, given the merger of the construction and maritime unions came into effect last week.

Resource and building employers are seeking to have the merger overturned by a Fair Work Commission full bench, which will hear their appeal next Monday.

Mr Howard told The Australian: “I am very disappointed that the public-interest-test legislation has not gone through the parliament and I would hope the government would re-present that.

“The question of whether you put something up or you just accept you are not going to get it through and don’t put it up becomes a tactical issue depending on the circumstances at the time.

“I took the view with these things it was better to keep putting something up and having it knocked over but different prime ministers will take a different view.

“I mean I certainly did that. For example with unfair dismissals. When we had legislation on industrial relations, we always put up unfair dismissals and we put it up 30 or 40 times.”

Mr Howard added that “just like we don’t like an ultra-concentration of commercial power, why should we feel comfortable about an ultra-concentration of union power, particularly given the track record of the two unions”. “I would argue the merger of those unions does represent the ultra-concentration of union power,” he said.

“I think the public-interest test ought to be applied; it’s applied to corporate mergers.”

There’s no question it was worth it: Corrigan

In an interview from Switzerland to coincide with the 20th anniversary of the former Patrick managing director locking out 1400 employees, Mr Corrigan said he had no regrets about the dispute during which he was allied with the Howard government to try to crush the influence of the Maritime Union of Australia.

“There’s no question it was worth it,’’ he said. “Even though it has plateaued in the last 10 years or so, productivity is still dramatically higher than it was before the dispute. When you measure it by crane rate, they were at least double what they were. It was an extraordinary worthwhile exercise from the point of view of the Australian economy and frankly, from the point of view of the company.”

Mr Corrigan said he told the Howard government in 1997 — months before the dispute — about his plan to remove the unionised workforce and bring in non-union contract labour.

“We had to tell them we had a plan to remove the workforce in certain circumstances,’’ he said

“There were certain circumstances in which we could declare the companies that employed these people bankrupt, and that’s what we did.”

He said the talks with the government occurred “definitely in 1997”. Asked to respond to longstanding claims that he engaged in a conspiracy with the Howard government to remove the union workforce, he said the company was responding to the Coalition’s desire to take on the MUA.

“People get this a little bit back to front,’’ he said. “If you remember Howard was elected on a platform of industrial reform. He had identified the waterfront as an area of reform. So it was after that, we went to see the government and said, ‘we agree with you about the opportunities here and the need for change but here’s how we would go about it’, and they started to think about that.

“I wouldn’t say they endorsed it but they certainly respected the fact that we had a point of view and they said, ‘what do we need to do to facilitate that?’ We said, ‘first of all, back off, don’t intervene when things get difficult and, secondly, we think redundancy payments ought to be funded by government and repaid out of the productivity initiative’.”

During the dispute, the government was rocked by revelations that federal cabinet devised a secret master plan in July 1997 involving the mass sacking and replacement of union workers on the waterfront with non-union labour. Mr Howard met Mr Corrigan in late 1997 and the businessman outlined action the company believed necessary. But Mr Howard said he provided little detail.

“We hoped that Corrigan had the commitment and the plan to implement reform and we provided the framework if he was so disposed to do it, but we were not plotting it, hand in glove,” Mr Howard said. “Obviously the willingness to advance the funding for redundancies was part of it. You had to do that. Otherwise why would he be the least bit serious given that other governments before us had caved in when something like this had arisen.”