Teachers take control to quell class violence

WHEN Stuart Blackwood became principal of a Perth primary school, teachers did little teaching -- it was more about crowd control

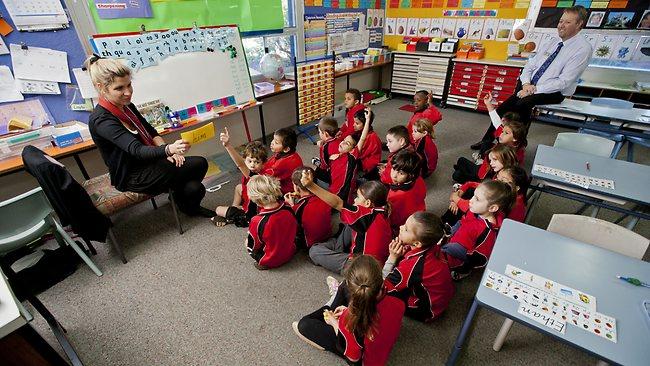

WHEN Stuart Blackwood became principal of Perth's Southwell primary school, teachers did little teaching -- it was more about crowd control.

In the first six months after arriving in September 2008, he had to stop two students trying to attack each other with axes, a teacher was attacked by a student wielding a pair of scissors and another pupil used a portable goal post as a weapon.

"In 2008, the behaviour was incredibly bad," Mr Blackwood said. "Teachers being accosted, there was lots of bullying happening, lots of racism in the school. It was really difficult to actually teach. It was more about crowd control."

There were also violent racial turf wars between Aboriginal children -- who make up half the school's 108 students -- and African refugee children.

As he set about trying to turn the disastrous situation around, his focus was safety, with more teachers and smaller classes.

The teachers agreed on behaviour guidelines across the school. The school adopted the mantra of "Every child, every chance, every day". Even if a student was suspended one day, they would be welcomed back the next; they were told that whatever problems they had at home or on the streets, they were safe at school.

Mr Blackwood and his staff also harnessed what they called the "critical mass" of students to turn the culture around. While 30 per cent of children were doing the wrong thing, the other 70 per cent were not. "The 70 per cent of kids needed to take power of the school," Mr Blackwood said. They used peer-group pressure. "We used the strong indigenous kids to actually be part of that critical mass rather than part of the violence side of things."

Once the behaviour started to turn around -- 80 students were suspended in 2009 and only one so far this year -- teachers looked at lateness and attendance. They noticed that few indigenous children were coming to the free morning breakfast because they were ashamed to let everyone know they had no food at home. So in late 2009, the school launched the "fitness and fuel" program where it became compulsory for all students to exercise and have sandwiches and fruit before school. It took away the shame factor.

"Virtually overnight," Mr Blackwood said, attendance shot up. Overall attendance went from about 85 per cent to the low 90s and indigenous attendance rose nearly 20 per cent, which meant a whole extra day of school a week for some children.

The school's achievements were recognised last week when it won the Milton Thorne award for an outstanding initiative for Aboriginal children.