Turnbacks best deterrent, says IOM chief

The boat turnback policy has been the single ‘biggest deterrent’ to asylum-seekers risking their lives at sea, says migration chief.

Australia’s boat turnback policy has been the single “biggest deterrent” to asylum-seekers risking their lives at sea, says the outgoing Indonesia country chief of the International Organisation for Migration.

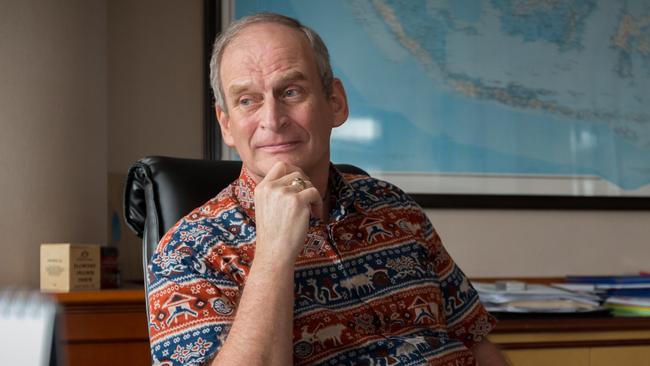

Mark Getchell, who helped negotiate the agreement under which Canberra has largely funded the agency’s support for asylum-seekers and refugees in Indonesia in return for authorities there intercepting boats, has also warned that changes to Australia’s immigration policy will encourage people-smugglers to resume their trade.

“What Australia is making it harder to do is to risk your life to seek asylum,’’ he said. “You don’t have to do that. You can seek asylum here. No one wants to spend the money on people-smugglers to get in a boat and end up in the same place they started.”

But, Mr Getchell added, people-smugglers and asylum-seekers in Indonesia were “watching politics in Australia” for signs of a policy softening.

“The feedback from various corners is that people-smugglers are talking to people,” he said.

“They’re testing the water to see if people are thinking about it or not. The first successful boat to reach Australian shores will help people-smugglers convince people they can make it now.”

The comments — made days after the UN’s refugee agency Indonesia chief Thomas Vargas said boat turnbacks “don’t work” because they pushed people into harm’s way and that his agency would continue to lobby to end the practice — highlight philosophical differences between the UN and its related organisation.

The IOM, an intergovernmental agency first established to help resettle WWII refugees, operates in more than 150 countries with an annual budget of more than $US1.4 billion ($1.95bn), much of it from Western nations, to promote “humane and orderly migration”.

Some human rights groups accuse it of acting as a proxy enforcer of border control policies for its donor states.

Boston-born Mr Getchell, who retires in March after 32 years with the organisation, has been involved in every major inflection point of Australia’s evolving immigration policy since the 2001 Tampa affair marked a hardened resolve to control the flow of asylum-seekers.

It was Mr Getchell, then a regional officer for the IOM, who commuted daily from the tiny Pacific island nation of Nauru in 2001 by rubber dinghy to the HMAS Manoora, scaling a rope ladder up the side of the ship to convince Afghan, Iraqi and Palestinian asylum-seekers controversially transferred at sea from a Norwegian tanker to come ashore and allow the UNHCR to process their claims.

He broke the news to those same asylum-seekers of the 9/11 terror attacks on the US that marked the beginning of the war on terror that would see millions of people flee conflicts across the Middle East and Afghanistan.

Mr Getchell oversaw the IOM’s key role in the first Nauru offshore processing centre, initially a tent city on a baking football field, which became the centrepiece of John Howard’s controversial Pacific Solution.

Mr Getchell said he threatened to withdraw IOM assistance unless the Howard government agreed to remove “prison camp” style wire from that early camp. Eleven years later — as IOM Australia country chief — he pulled the pin on IOM involvement when Julia Gillard reopened Nauru in 2012, citing concern at the overly punitive nature of the new camp.

He has watched Australian immigration policy yoyo with each leadership change, asylum boat arrivals rise and fall accordingly until 2012, when 300 boats in one year prompted the former Labor government’s dramatic policy U-turn.

Weeks before his retirement, he laments hardening global attitudes towards refugees, which he traces back to the September 11, 2001, attacks on New York, the Pentagon and Pennsylvania which killed 2996 people and injured 6000 more.

“I think 9/11 played a major role in allowing governments to demonise migrants as potential security threats,” Mr Getchell said. “(John Howard’s) Pacific Solution gained support because of its ‘lucky’ timing,” he added.

Still, he is reluctant to criticise the current turnback policy under Operation Sovereign Borders, the successor to the Pacific Solution.

Mr Getchell lost friends on SIEV X, a criminally overloaded Indonesian fishing boat that sank with 353 asylum-seekers on board in October 2001 en route to Australia. The family of eight Iraqi refugees, including five children, drowned. Only 43 people survived, and questions remain over why the vessel went undetected given intense government interest in deterring boats during a federal election campaign.

In 2010, he sat in Canberra trying to calm an IOM colleague on Christmas Island as she watched a boat full of asylum-seekers smash onto rocks and bodies spill out. Fifty people died, including 12 children and three infants, in the worst peacetime maritime incident in Australian waters in more than a century.

“She was on the phone to me screaming and crying, saying: ‘There’s nothing I can do. There are women and children, babies, bodies’,” Mr Getchell recalled this week.

“So my bottom line is, if that policy (boat turnbacks) can stop that happening, then that is a positive thing. Now, treating people with dignity is the other side of it.”

Mr Getchell said he had “no problems” with the first Nauru offshore processing centre, in which asylum-seekers were free to move around, and insisted they were treated with dignity as the IOM charter demanded.

“But when they were reopened (in 2012), they were far more restrictive and detention-focused,” he said. “I would have been happier if people were not treated as though they were in high-security detention.”

IOM’s only involvement now with those centres is to help people who want to return home.

In Indonesia, however, Mr Getchell said it was Australian funding that allowed IOM to “treat people with dignity, get them out of immigration detention centres, which we have finally been able to do, try to get their kids into school, and give them as much of a life as possible” while they awaited resettlement.

The details of that agreement between Australia, Indonesia and the IOM have never been revealed, though the original terms are believed to have required Indonesia to detain asylum-seekers intercepted on their way to Australia. Under Mr Getchell, those detention centres are being closed down and refugees moved to community housing.

The money Australia provides to the IOM to support 8620 of Indonesia’s 14,000-strong refugee and asylum-seeker population — about $US40 million annually — was capped last year to those who arrived before March 15. Five thousand refugees who did not submit to detention receive no IOM support. Those who have come since March 15 are on their own. That has created a new dilemma, with several hundred refugees with no money to support themselves camped outside remaining detention centres hoping to be let in.

Notwithstanding the cuts, Mr Getchell aims to increase services to refugees in Indonesia now facing resettlement waits of a decade or more as some countries slash their quotas and others prioritise refugees from other parts of the world. He said the psychological burden on refugees in Indonesia was visible as waiting periods lengthened, and conditions in countries such as Afghanistan and Syria continued to deteriorate.

Yet he credits the very hardships created by draconian government policies — the slowdown in resettlement, the ban on refugees working in Indonesia, and “the fact you’re not going to succeed in getting to Australia by boat” — with keeping “a lid on the overall caseload for Indonesia”.

“We are just dealing with symptoms here,’’ Mr Getchell said, conceding: “Nobody’s solving the problems that are creating this (movement) in the first place.

“But the end result at this moment — after years of dealing with this — is that from a peak of more than 300 boats a year there are now no boats leaving. People are no longer dying at sea between Indonesia and Australia, and I count that as a success.”