Reforms failing to close indigenous schools gap

EFFORTS to close the gap in education for indigenous students have stalled, reflecting the slow progress in lifting literacy and numeracy skills.

EFFORTS to close the gap in education for indigenous students have stalled, reflecting the slow progress in lifting the literacy and numeracy skills of all students across the nation, despite the extra billions of dollars spent in schools.

Literacy and numeracy test results released yesterday show indigenous students are closing the gap in a couple of areas, notably the reading standard among Year 3 students, but on average are improving at the same rate as non-indigenous students, leaving the gap intact.

The slow progress in the National Assessment Program - Literacy and Numeracy tests casts doubt on the federal government's goal of halving the gap in literacy and numeracy skills between indigenous and non-indigenous students by 2018, and being among the top five nations in the world by 2025.

The results come a week after the release of an international test that showed one in four Australian primary school students failed to meet the reading standard for their age level.

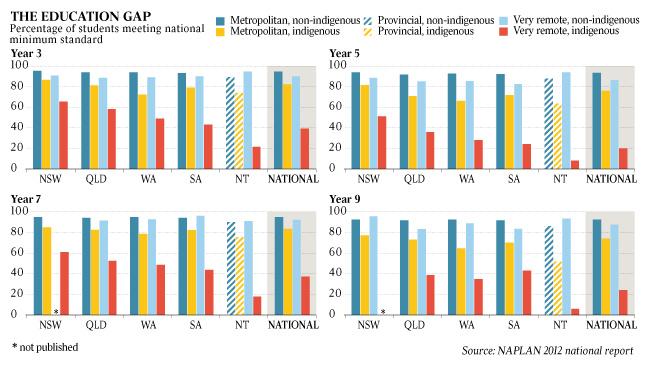

Students attending school in the cities tend to perform better in the NAPLAN than students in provincial or remote schools, and the trend is exacerbated for indigenous students.

Indigenous students at city schools score an average 15 points lower than their fellow non-indigenous students on reading tests. The gap widens in regional and remote areas, with indigenous students in very remote schools scoring an average 60 points lower than non-indigenous students in the same schools. The biggest gap is in the Northern Territory.

Only 8.6 per cent of indigenous students in Year 5 attending school in very remote areas of the Territory met the minimum standard in reading compared with 94 per cent of non-indigenous Year 5 students in the same areas.

School Education Minister Peter Garrett described the disparity yesterday as "an appalling statistic".

When the same group of indigenous students were in Year 3 in 2010, 28.5 per cent met the minimum standard in reading.

A similar decline was apparent in the writing skills of indigenous Territory students in very remote areas, with 13.6 per cent meeting the minimum standard for Year 5 in 2008, falling to 7.7 per cent meeting the Year 7 standard in 2010 and 3.3 per cent of these same students, now in Year 9, meeting the standard this year.

Overall, the rate of improvement seen in the early years of NAPLAN testing has slowed. Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority chief executive Rob Randall said: "We are essentially coasting."

About one million students in Years 3, 5, 7 and 9 sit NAPLAN tests each year in reading, spelling, grammar and punctuation and numeracy. Girls score higher on average in the literacy tests while boys have higher average scores in numeracy, although more primary school girls reach the national minimum standard than boys.

Parents' levels of education are also linked to a child's results, with almost 98 per cent of students with parents who have a university degree meeting the minimum standards compared with 84.5 per cent of students whose parents finished only Year 11 at school.

Year 3 students' reading is one of the few areas where the gap in achievement between indigenous and non-indigenous students appears to be closing, with 74.2 per cent meeting the minimum standard this year compared with 68.3 per cent in 2008. By comparison, the proportion of non-indigenous students meeting the standard rose 1.2 percentage points in that time. Reading in Year 7 also improved, rising from 71.9 per cent meeting the standard in 2008 to 74.4 per cent this year.

The Year 3 indigenous students who sat the first NAPLAN tests in 2008 also have improved during the past four years, with 68.3 per cent meeting the standard in reading in 2008; this year, as Year 7 students, 75.2 per cent met the standard.

The proportion of their non-indigenous peers meeting the standard rose about 1.5 percentage points in that time.

Mr Garrett said the average performance of indigenous students in reading and numeracy was two to three years below the average of non-indigenous students, rising to about four years in the Northern Territory.

Students from remote areas on average were the lowest scoring group in Australia, with 51.5 per cent meeting minimum standards compared with 93.5 per cent of metropolitan students.

"It's unacceptable for us as a nation to have these gaps, whether it's between indigenous Australians or not, finishing high school as much as three or four years behind their counterparts in suburban or city schools," Mr Garrett said.

"It's absolutely unacceptable for us to have such a big gap between kids from low socioeconomic backgrounds and those from better-off backgrounds in terms of their educational attainment."

While there were some "gentle inclines" in the nationwide NAPLAN results, there was nowhere for state education authorities to hide from responsibility for their schools' performance.

"There should not be a single education minister in a state, nor a single senior state education bureaucrat, who can take any comfort from these NAPLANs at all," he said. "We need to react urgently, in a focused way, with a national plan for school improvement agreed by all."

NT Education Minister John Elferink said the commonwealth had to bear some responsibility for the problems in remote areas, given the intervention, introduced by the Howard government and extended by Labor, was meant to fix the situation. Mr Elferink said many remote indigenous students only spoke English at school and there was a need to improve its teaching in their schools.

He said the bigger issue was not the comparison between indigenous and non-indigenous students, but the socioeconomic backgrounds of children.

Opposition education spokesman Christopher Pyne criticised calls by Mr Garrett and the Australian Education Union for extra funding. Labor had poured money into education for little return. "Despite the Gillard government's boast five years ago of an 'education revolution' and additional spending on school halls and computers, it has had little impact on student outcomes," Mr Pyne said.

Mr Pyne said improving teacher quality, developing a robust curriculum and giving principals more autonomy would boost performance without costing more.

AEU federal president Angelo Gavrielatos said the results confirmed the urgent need for targeted investment to reach the kids who need extra help.

"It's unacceptable that these results continue to show significant achievement gaps between students from poorer backgrounds and those from more affluent backgrounds, as well as between indigenous and non-indigenous students," he said.