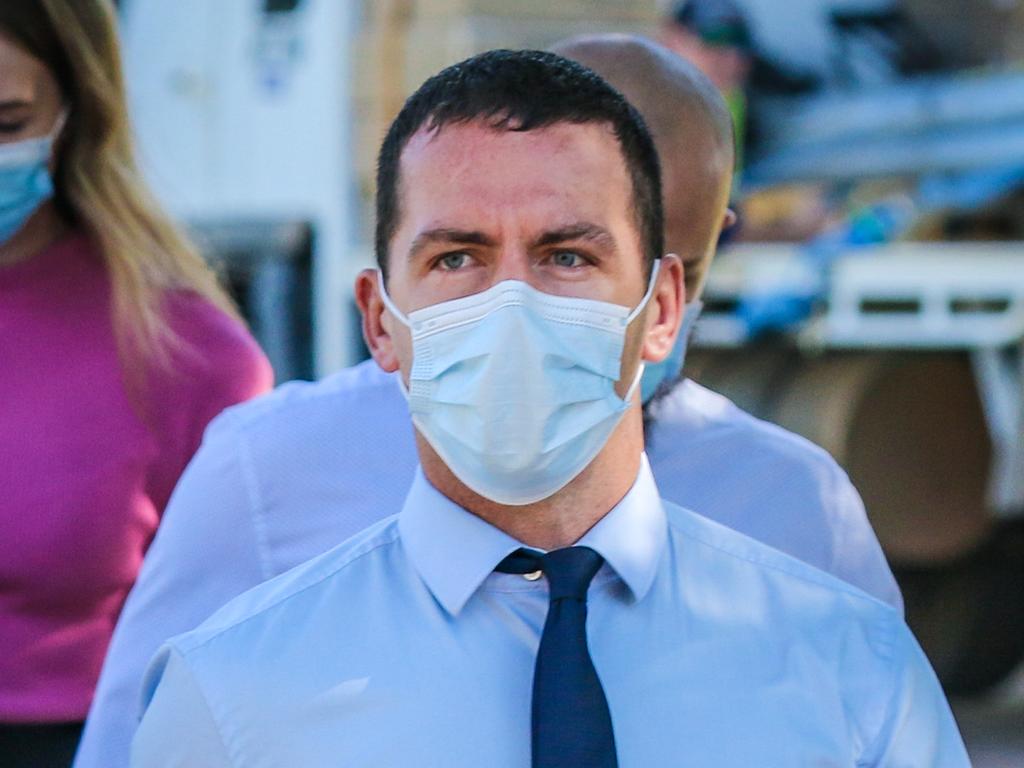

Zachary Rolfe: NT cop murder case hinges on ‘good faith’

A legal showdown is underway to determine whether Zachary Rolfe can claim he acted in ‘good faith’ in the alleged murder of an Indigenous man.

The nation’s highest court is being asked to decide whether Northern Territory legislation effectively puts police officers above laws they are meant to enforce.

Crown prosecutors in the murder trial of decorated policeman Zachary Rolfe in August persuaded the High Court to intervene and delay the proceedings on the basis that without that, Constable Rolfe could be acquitted on false grounds.

Constable Rolfe is accused of murdering Aboriginal teenager Kumanjayi Walker during a botched attempted arrest in the outback community of Yuendumu.

The case has divided many, with Constable Rolfe’s supporters convinced he has been wrongly charged, while sympathisers with Walker’s family see his death as a Black Lives Matter killing on Australian soil.

Constable Rolfe wants to use an immunity clause in police administration legislation that says officers are not liable for acts done in good faith in the course of their duties. The Northern Territory Supreme Court has ruled he can.

The immunity defence rests on whether Constable Rolfe was exercising police powers and functions when he shot Walker.

The Supreme Court’s full bench in August dismissed a prosecution argument that Constable Rolfe could not conceivably have been exercising the power of arrest if, by shooting Walker, he was trying to kill or harm him.

Prosecutors now want the High Court to find the Supreme Court was wrong.

Philip Strickland SC, acting for the crown, told the High Court on Tuesday the defence should be struck out because a police officer could be wholly protected from criminal or civil liability even if they don’t act appropriately in the course of their duties.

“It would mean that any activity of a police officer would not be tethered to any notion of reasonableness,” he said.

“The significance of an incorrect ruling is that the respondent could be acquitted of murder on an incorrect basis.”

In agreeing in August to hear Mr Strickland’s application, judge Jacqueline Gleeson said murder acquittal from an error of law would be an injustice of a “different magnitude”, noting that Constable Rolfe was a policeman and his alleged victim an Aboriginal man.

The High Court is hearing the prosecution’s application for special leave to appeal and arguments in that appeal simultaneously. If it agrees to rule and finds in the prosecution’s favour, Constable Rolfe could still use the defence of self-defence or of acting reasonably in his duties.

If it declines to rule or finds in favour of Constable Rolfe’s defence, the prosecution will have to show beyond reasonable doubt that he was not acting in good faith to obtain a conviction, meaning Constable Rolfe’s past conduct may become a significant issue in the trial.

Under NT law, if Constable Rolfe were to be acquitted using the immunity defence and the ruling was later found to be incorrect, he could not be retried.

Mr Strickland said a trial was of national importance whenever it involved a police officer using lethal force. “That is a matter of public importance, and the public importance is more poignant when the citizen is Indigenous … having regard to the controversial history of the state’s use of power against Indigenous Australians.”

Chief Justice Susan Kiefel on Tuesday said it was the full bench’s task to decide whether the jury would be asked to determine if the shooting had occurred in “good faith”.

Bret Walker SC, for Constable Rolfe, said leave should not be granted as it would further delay the criminal process. “This is a very good ... by which we mean egregious example of threatened fragmentation of the criminal process as a kind ... that this court would (usually) tend strongly against.”

The special leave application will return to the High Court on Wednesday.