Yes23’s Rachel Perkins says appalling living conditions in Alice Springs highlight the need for the voice

I’ve been to slums in India and Myanmar as desperate as this. But they weren’t on the outskirts of a prosperous regional city in a wealthy developed country.

Rachel Perkins is keen to show me around Alice. We pile into a tiny hatchback, Perkins, me and three older Arrernte women who are her aunties, or nieces, in the blackfella way of things. The celebrated filmmaker divides her time between her digs in Sydney and her mob in Alice Springs. For the past few years she has been recording the traditional songs and stories of these women, and they chat and joke as we make our way through town.

The kerbs and guttering end and the desert begins. We turn off the main road and down a track through sparse scrub to Irrkerlantye, or White Gate. For many years this was home to the woman in the front passenger seat, Aunty Felicity Hayes. She raised her kids at White Gate and members of her family have been here for 40 years – longer if you count the old days.

This is the site of a campground her forebears used for thousands of years when they came to trade at the nearby Todd River or to meet other mobs for ceremonies.

There’s nothing noble or romantic about it now. It’s a disgrace to all of us. White Gate is one of Alice Springs’ squalid and shameful town camps. I’ve been to slums in India and Myanmar, and Afghan refugee camps in Pakistan, as desperate as this. But they weren’t on the outskirts of a prosperous regional city in a wealthy developed country.

“I want people to see this,” Perkins says with tears in her eyes. “I just don’t think people understand.”

This is one of about 20 town camps around Alice, home to 1500 people, all of them Indigenous. Let’s call it what it is – a slum. Eight or so tin shacks in various states of disrepair are dotted around a tiny tin-roofed church propped up by bush logs. “Jesus loves me this I know for the Bible tells me so,” reads a hopeful inscription on a bench.

Aunty Felicity leads me up to one of the tin shacks where her niece lives. Or exists. It’s about 4m by 3m. There’s no sink. There’s no toilet. No fridge. On the dirt floor is a double mattress and beside that are two single mattresses. Filthy blankets and clothes are strewn across the beds, a plastic milk crate is the only piece of furniture.

Her niece lives in this hovel with her two kids and her granddaughter. In summer they head into town to sit in airconditioned shopping centres. In winter it’s freezing. The outcomes for the kids reared in these camps are as bad as you’d imagine.

Aunty Felicity remembers Rachel’s father, Charlie, visiting to deliver blankets, coats and food. “My aunty had been fighting to get houses built here, but she passed away,” she says. “So I’m the one fighting with the government now.”

Like the other camps, White Gate is a sore that has festered for decades. There’s money to build the houses and the reasons they haven’t been built are entangled in titles. Chief ministers, cabinet ministers and prime ministers have all visited these camps. They’ve all left, as appalled as I am, and have pledged to do something. Meanwhile, the inhabitants of White Gate continue to live in squalor.

It boils down to a lack of political clout on one side and a lack of political commitment on the other.

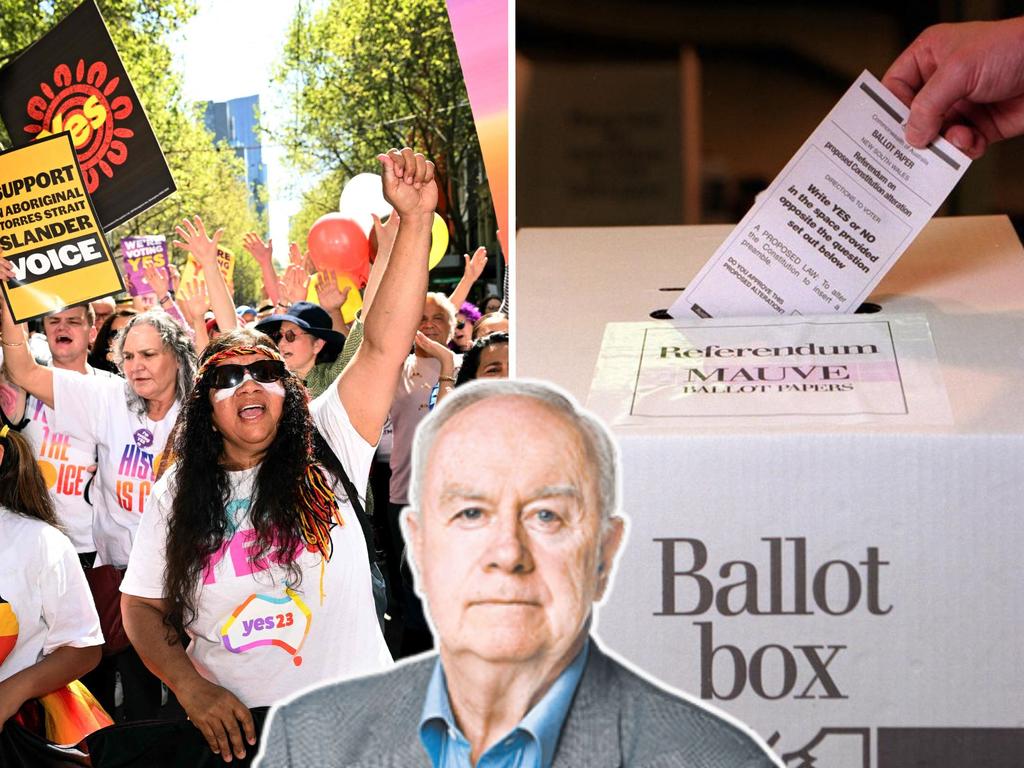

Rachel Perkins is hoping to swing this political pendulum back towards her mob. She has put her life on hold this year to be co-chairwoman of Yes23 and is campaigning full time for the voice. She has been handing out pamphlets and talking to punters in shopping centres; she’s fronting town hall meetings; she’s crisscrossing the continent and giving dozens of interviews with radio stations and newspapers.

The woman behind a stream of successful Australian dramas including Bran Nue Dae, Jasper Jones and Redfern Now, and incisive documentaries The Australian Wars and First Australians, wants Australians to focus on the issues in places such as Alice. She wants us to feel for their poverty, their disease, their overcrowded housing, and for us to know that all these factors lead to them being jailed at appallingly high rates and sentences them to die decades earlier than the rest of us. She wants us to believe that her mob deserves the same opportunities to lead happy, healthy lives that the rest of us take for granted.

But she also wants us to know there are solutions, there is hope, and those solutions come from the communities themselves. She wants us to believe an Indigenous voice to parliament will enhance and encourage these community-based solutions, rather than programs being foisted on them from Canberra.

“This referendum is like Halley’s comet,” Perkins says. “Chances like this come around once in a lifetime for our people.”

The great Australian storyteller has an epic family tale of her own. It’s as grim as White Gate.

It starts with a massacre at a place called Blackfellas Bones, to the northeast of Alice. Her great-grandmother, Nellie Errerreke Perkins, survived. Nellie’s father was shot. “She and her sister were spared,” Perkins says. “And, as Dad told us, chained to a tree and just used by policemen.” The two girls ran away and Nellie ended up with an Irish miner. “My grandmother describes him as a good man, and he took Nellie in and she had three children to him.”

One was Rachel’s grandmother, Hetty, who worked on cattle stations as a ringer and a housemaid. Hetty had three children to white cattlemen, a boy and two girls. The boy, Bill, worked as a stockman on his father’s run, but the girls were sent away to live with the Salvation Army. “He (the squatter) just sent them away and said, ‘There’s no future for you, you’ve got to go.’ ” Charlie would never meet his older sisters.

Eventually, Hetty walked off the station and into Alice Springs and got work at the Bungalow, where a “part Aboriginal woman called Topsy Smith” had set up a school, “a half-caste home” for Aboriginal kids.

The Bungalow was moved to the Telegraph Station building into what officially was known as the Native Institution. Hetty had more children, one of them being Charles, Rachel’s father. Charlie’s father was Martin Connolly, a Kalkadoon man from Mount Isa, who came to Alice Springs for work, then drifted off. Charlie met him only once.

We hop in the hatchback and head for the Telegraph Station. Built in 1872 on the telegraph line between Darwin and Adelaide, it was the first European building in Alice Springs. It’s an elegant stone colonial structure. Charlie and the other kids all lived out the back, in tin sheds with concrete floors. Perkins shows me the kitchen of the main building.

“Dad was born on the table in here,” she says as we peer in. “As kids, he would always take us out here and we’d run around the Bungalow. It was the closest thing he had to home … his ashes are scattered here. He had some beautiful childhood memories, like swimming in the creek and bush medicine.”

And it left him with some horrible memories too. He met his grandmother Nellie only once. He touched her through the fence when she came to beg for food. Full-blooded Aboriginal people weren’t allowed on the grounds.

Charlie was lucky, his mother worked there. Some of the other kids were dropped off by parents who lived on the stations, hoping they’d get an education. Others were forcibly removed, being “half-castes”. They’d arrive in a cage on the back of a ute and some would lose contact with their families forever.

An Anglican priest at the Bungalow, Father Smith, “a very good man”, came to Hetty and offered to educate Charlie and some of the other children in Adelaide. She saw it as an opportunity for him to get ahead. Aged eight, he caught the train south to the St Francis House for Aboriginal Boys, and would return to Alice once a year at Christmas to see his mother.

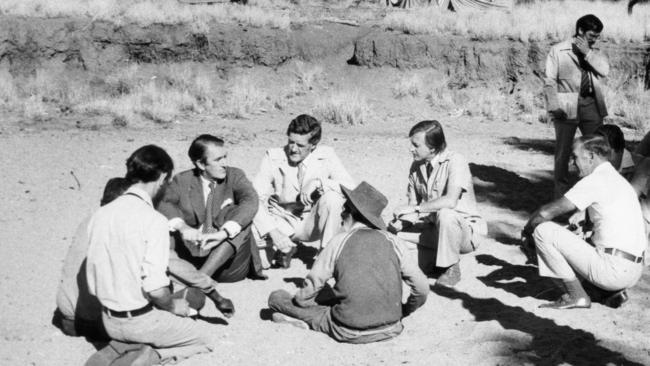

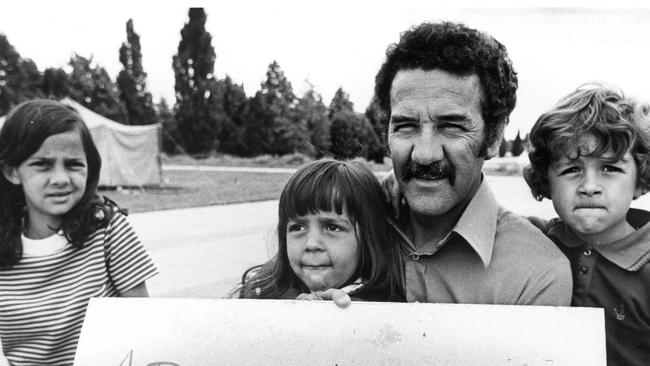

Charlie Perkins played professional football and was invited to trial in the English Premier League for Everton FC. He put himself through night school, playing and coaching, and went on to become one of the first Aboriginal people to complete university – graduating from the University of Sydney in 1966.

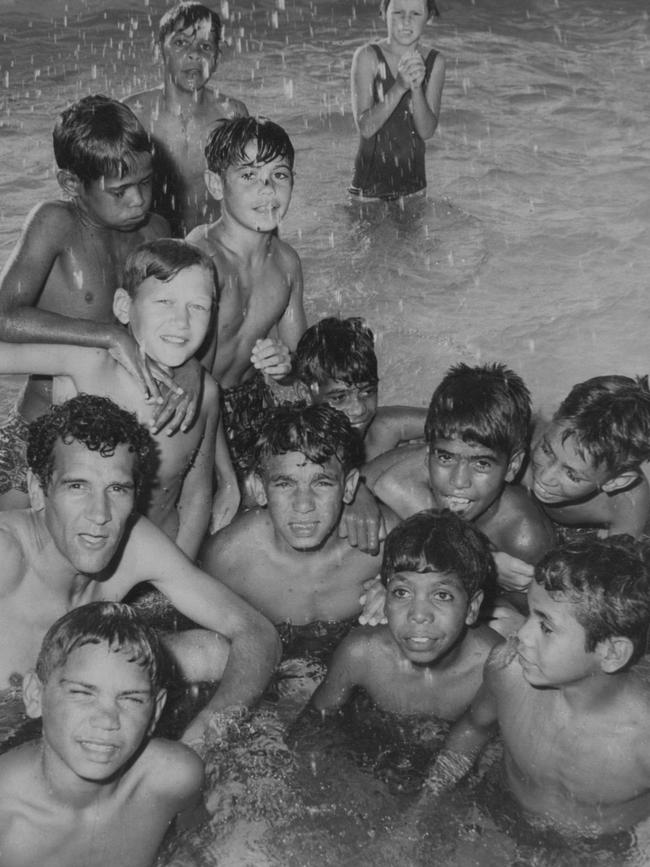

In 1965 he led the Freedom Ride – a busload of students and activists who travelled through NSW, highlighting racism. In some towns, such as Moree, black kids were banned from the swimming pool. In Walgett, black veterans were banned from the RSL club. The Freedom Ride was Australia’s Rosa Parks moment – Parks became a pivotal figure in the American civil rights movement when she refused to give up her bus seat to a white passenger and was arrested.

Charlie Perkins also played a role in the 1967 referendum that gave the commonwealth power to make legislation specific to Indigenous affairs, spent his whole life advocating for his people. He died in 2000 from renal failure, having never been a smoker or a drinker. His obituary in The Canberra Times said he “was perhaps not only the most influential Aborigine of modern times but also must be numbered among the outstanding Australians of the century”. Charlie Perkins, born in the Native Institution, Alice Springs, was honoured with a state funeral.

Rachel Perkins says he remained extremely close to the kids he grew up with at the Bungalow, some of whom would go on to become important leaders, such as activist, artist and footballer John Moriarty, the first Indigenous player to be selected for the Socceroos. Former Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission chairwoman Lowitja O’Donoghue was in the girls home next to where he was in Adelaide.

As we leave for our next meeting, Perkins has another story to tell. “There was a bloke who was in charge of the Native Institution and he was raping the young girls and my Nanna Hetty found out about it. She supported the young girl who was raped, who wrote a letter to authorities and reported it to the police,” she says. “This is the 1930s, remember.”

“I am longing to have someone to help me,” the girl’s heartbreaking statement read. “Mr (GK) Freeman (the superintendent) got hold of me and put me on the bed in his room. He took off all my clothes … I used to let him do it as I was frightened. Everybody laughs at me when they see me go with him.” Other girls gave statements, saying they’d also been abused.

Hetty went to court to give evidence. It was incredibly brave of both to testify against the white manager. Freeman was convicted of having had “carnal knowledge” with a “16-year-old half-caste girl”. He served three months in jail. Hetty would be accused by him of being “a noted harlot” with “NO knowledge of the Bible and does NOT believe in God”. The girl would discover she was pregnant. We are driving through Alice and Perkins says: “This fella we are about to see, he’s a descendant of that young girl who was raped.”

Graeme Smith is chief executive of Lhere Artepe Aboriginal Corporation, which holds native title over much of Alice Springs. We sit in his office and he explains the intricacies of the town camps and why there has been so little action at White Gate for the past 40 years. “White Gate is not actually a town camp, it’s a little outstation,” he says. “People from southeast of Alice Springs, before bitumen roads, before white people, used to camp there at White Gate before they’d do their trading or their ceremony. It’s always been a place that’s been occupied by those people – they come and go. The family that lives there now have turned it into their home – it just happens to be on crown land.”

Smith says his organisation has been in negotiations with the NT government, which holds the crown land title over the land at White Gate. Some blocks there are under native title. It would be a fairly simple land swap. “So that’ll change it from crown land to private property owned by Aboriginal interests,” he says. In the end, it doesn’t seem all that complicated.

“When White Gate gets the secured title then it can start getting infrastructure and houses,” he says. “No government will fund infrastructure on crown land and that’s where White Gate’s been forever.” He first started working on this issue in 1992.

He continues: “This is exactly the reason why we need the voice … we don’t believe that politicians are hearing our voice. It happens, over and over. I was listening to Paul Kelly’s song about Vincent Lingiari the other day: ‘We have friends in the south, we’ll sort it out.’ Well, my people are still waiting and dying. Those words are still what we are waiting for today.”

We move on to the story of his grandmother, Tilly. “My grandmother was the one in the Bungalow with Charlie,” he says. “There was a bit of history with Nanna Tilly that the family knows, and we are actually quite proud of the role she played. While it was a dark period, we are very proud of the leadership role she played. You can imagine how hard it would have been to turn on a white administrator and hope that the government listened. It could have gone the other way. It was Hetty and Nanna Tilly who put the spotlight on the Bungalow.”

The Purple House is an incredible Indigenous-run health facility that delivers renal treatments and other health services to remote communities of central Australia. Perkins takes me there to show me the great things that can be achieved when governments listen and support grassroots Indigenous organisations rather than imposing solutions from Canberra.

Perkins’s sister, writer and curator Hetti Perkins, helped establish the Purple House more than 20 years ago when Papunya Tula artists produced a stack of paintings that were auctioned at the Art Gallery of NSW and more than $1m was raised. The chief executive is an “old bush nurse”, Sarah Brown, who has been with the organisation since the beginning. She now runs a multimillion-dollar health service with more than 200 staff, yet she wanders around with a pair of electrical pliers in her back pocket, just in case some of the oldies need their toes and fingernails clipped.

“In some remote communities the rate of kidney disease is 15 to 30 times higher than the national average,” Brown says. The reasons are many: poor housing, poor diet, premature births, multiple infections as a child and “just poverty”.

The idea for the Purple House started in the Pintupi community. They were witnessing their elders going off to Alice Springs for renal treatment. They’d never return. They wanted these elders to be treated on country. “They went to the politicians, who told them to bugger off,” says Brown.

So the artists of the community got together and raised $1m with the aim of getting one dialysis machine in one community. Twenty years later they have 58 dialysis machines in 19 remote communities. Last year they administered more than 10,000 dialysis treatments “out bush”. The board is still fully Indigenous.

The results have been spectacular. “Suddenly the central Australian figures (for survival) went from shit to better than Darwin and other places,” says Brown.

“So now, our patients are living longer than whitefellas on dialysis in Sydney and Melbourne.”

Brown is an ardent supporter of the voice and is certain it will make a difference. “We know that communities have the answers to their issues,” she says. “They’re sick of the next bright idea to come out of Canberra. When we set this up we had independent money, which meant that cultural priorities were front and centre of everything. It’s about being on country, doing things culturally the right way, having bush medicine, having the right people, and looking after each other and holding people close … You can’t prescribe that from Canberra.”

Perkins and I pop into the Children’s Ground, another successful bottom-up organisation that has been working with schools, and preschoolers, to ensure cultural knowledge and language are taught to kids by their elders as part of their education.

Perkins gives a rousing speech to the staff, holding a copy of the Constitution. “I’ll just talk you through what the proposal is.” She takes them through the various Indigenous advisory bodies that began in the 1970s. All of them were scrapped.

“We’ve been banging our head on the door for 50 years, trying to get them to listen,” she says. She waves around the Constitution. “It’s only a tiny thing.” She explains that the Constitution says there will be an army, but it doesn’t say how many people will be in that army and how many tanks it will have. “So it’s like the basic rule book and the parliament has to follow it.

“And so what is being proposed? This idea has two elements to it. The first is recognition … and that is that our people have been here for a long time, we would say 65,000 years, and so people say we should be recognised in this document.” The second part is a voice to advise parliament and the bureaucrats. “I want Australians to understand that if we had a voice, organisations and people like you, who know what is good for our communities – you work on this every day – have the solutions. I want a voice so your voices can be heard, rather than people in Canberra deciding what happens and putting it on us.”

Later, at the Bungalow, she says it will be devastating for her people if Australians vote No, that it would say Australians don’t care about Indigenous issues. But she can’t contemplate that. She says they’ve assembled the largest team of volunteers for a campaign and hope to have 75,000 of them knocking on doors, making phone calls and staffing booths before October 14. “We have captains in every electorate co-ordinating those volunteers,” she says. “It’s the biggest volunteer turnout for a campaign ever.”

Perkins is hopeful her fellow Australians will see things as she does. “It’s not a silver bullet but it means that in our democracy our people will always have a place at the table, and that it will be respected because it’s in the Constitution.” What do you think your father, Charlie, would say if he could talk to you now, I ask? She bursts into tears. “I don’t know,” she says between sobs.

“The thing is he would be here if he didn’t die early from kidney failure. But he’s dead because he had kidney failure, like so many of our people. I so wish he was here because if he was, he’d be leading this and I wouldn’t have to.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout