Writer Nicholas Jose haunted by the horror of Beijing, 1989

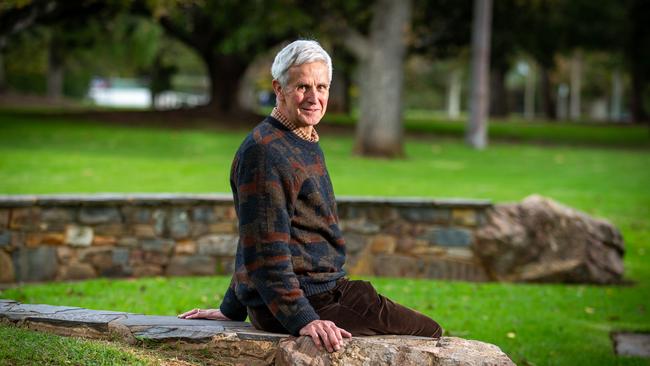

This Wednesday, novelist Nicholas Jose, now an English professor, will pause to recall the most dramatic day in his life.

This Wednesday, novelist Nicholas Jose, now an English professor at Adelaide University, will pause to recall the most dramatic day in his life, 30 years ago, when China’s Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo knocked on his Beijing door desperately seeking shelter.

On June 4, 1989, the People’s Liberation Army crushed student protesters, killing hundreds at least — and possibly thousands — of those who had remained in central Beijing after martial law was imposed.

The “Four Gentlemen” of Tiananmen Square, older intellectual figures, in their 30s, were among the last to leave. They had earlier staged a hunger strike to support the students, then as the military approached on the night of June 3, persuaded hundreds to depart, saving many lives.

The best known of the four at the time was Hou Dejian, a feisty Taiwanese pop musician whose Descendants of the Dragon had become a student anthem.

But Liu became globally famous in being awarded the Nobel in 2010, which he was unable to receive since he was by then in jail. After Tiananmen, he went on to spend a total of about 13 years in prison, and was incarcerated when he died in 2017 of liver cancer.

On June 3, 1989, Jose, then the cultural counsellor at the Australian embassy, had travelled to Shanghai with writer and translator Linda Jaivin to start planning a TV series on one of his novels. He switched on the TV at the Hilton, and found CNN was live-streaming from Tiananmen “with all the hotel staff in my room alongside, watching in horror”.

He flew back the next day, and the embassy sent a convoy of cars to escort him safely across a Beijing now littered with wrecked vehicles, fires and tanks.

Soon after arriving at his flat, there was a knock. It was the Four Gentlemen, who had somehow escaped, and “wanted somewhere quiet and safe to draft a statement”, which would become a core document of those turbulent times.

In the afternoon of the next day, Jose and Ms Jaivin took Mr Hou to the embassy, where he obtained asylum. An army sniper began to target the diplomatic compound, prompting the embassy to evacuate its staff.

“I asked the remaining three what they wanted to do,” Jose said. “Two who were less known — Zhou Duo and Gao Xin — decided they would cycle home. Then I packed my bag and drove with Liu to the embassy” through strangely empty streets.

“I stopped outside, the gates opened, and I asked Liu whether he wanted to come inside, and thus effectively to Australia. He said no, he wished to stay in China. He would figure something out.”

Liu walked to a nearby friend’s home and borrowed a bike. A couple of hours later, Jose said, “his girlfriend called me and said he had been seized while cycling and taken off in an unmarked van. I felt terrible, devastated, helpless”.

Jose left the next day for Canberra, where he heard the Four Gentlemen’s statement, “a fairly abstract call for justice, and for the world to support Chinese people in their quest for democracy and freedom”, being read on the radio news in the taxi from the airport.

He returned soon, and cultural connections continued, with Australian pianist Roger Woodward rapturously received in Beijing for his performance of Chopin’s Revolutionary Polonaise.

Liu eventually re-appeared, on TV, “looking beaten-up, and making a kind of confession. We smuggled a woollen jumper in to him in prison with a Made in Australia label, which he understood as a message.”

Jose saw him last in Beijing in 2007, a year before his final, fatal jailing for “inciting subversion of state power”.

Jose said “the flow-on effect” of the Tiananmen killings — after which then prime minister Bob Hawke said all 40,000 Chinese students in Australia could remain here — “has been significant for Australia, because of all those people who stayed and prospered and contributed to business, research, the arts. And now their children are doing likewise.”

He said “it was not just a terrible thing that happened in a foreign country. Australian history has been changed by Hawke’s tears.”

INQUIRER P18