Why political elite live longer than ordinary people

Better advantages in healthcare is one reason politicans enjoy longer lifespans than the general population, a new study finds.

Politicians are paid well, travel in comfort and receive generous pensions in retirement, but they also live several years longer than the general population, a new study has found.

An analysis of the mortality rates and life expectancies of almost 58,000 elected representatives to national parliaments in 11 countries over two centuries shows the political elite living up to seven years longer than the people they represent.

At age 45, an Australian federal MP can expect to live another 41.2 years, compared with 37.8 years for a person of the same age and gender. The 3.4-year difference in life expectancies is down from a peak of 7.5 years in the 1980s, with improvements in community health one of the possible explanations for the closing of the gap.

The study by British and Australian academics has just been published in The European Journal of Epidemiology and includes politicians elected as far back as 1816 in France, 1838 in Britain and 1850 in the US and the Netherlands.

In Australia, the study includes 1719 representatives since Federation, 12 per cent of whom are women, with an average age of 44 when first elected.

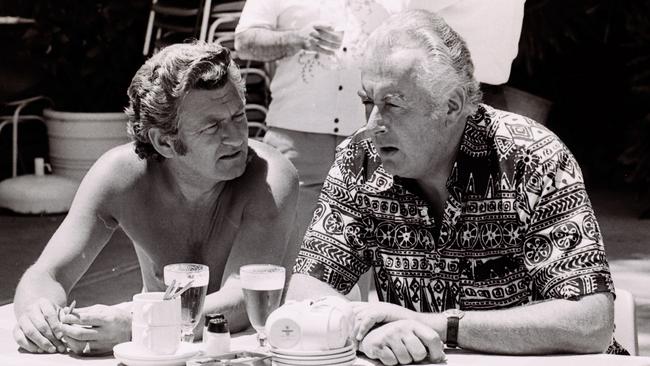

Of the 15 most recently deceased prime ministers (from Ben Chifley in 1951 to Bob Hawke in 2019), the average life span was over 82 years. Of the four former PMs who died this century their average age was over 90 years, with Gough Whitlam dying at 98 in 2014.

When he disappeared while swimming in December 1967, Harold Holt was 59, the same age as Anthony Albanese is now, making him the prime minister with the shortest life span.

The study found large relative and absolute inequalities favouring politicians in every one of the eleven high-income democracies. In some countries, such as the US, relative inequalities are at the greatest level in over 150 years.

In the US, where congressional Democrats are divided over whether 79-year-old President Joe Biden should run in 2024 for a second term, the study found American politicians at age 45 could expect to live to 86.4 years, compared with 79.5 for other citizens in their cohort.

Of US presidents who died this century, Ronald Reagan and Gerald Ford were 93, while George HW Bush was 94. Jimmy Carter will be 98 in October.

In almost all countries, politicians had similar rates of mortality to the general population in the early part of the 20th century. Over the second half of the previous century, relative mortality and survival differences (favouring politicians) increased considerably.

The gap may be narrowing due to improved public health, but researchers are wary of the long-term effects of Covid and pre-pandemic trends such as so-called “deaths of despair” that reduced US life expectancy.

In the second decade of this century, the life expectancies of politicians aged 45 years were remarkably similar between countries, ranging from another 39.9 years in Germany to 43.5 years in Italy.

The authors noted politicians’ salaries in many countries are well above the average population levels: “For example, incomes of politicians in Australia were between two and six times the average wage over the 20th century.”

Co-author and Queensland University of Technology health statistician Adrian Barnett told The Australian politicians were an ideal group to observe the evolution of inequalities across countries and time.

“Politicians accrue many life advantages prior to and in office, including the benefits of money, education and better lifestyle,” Professor Barnett said.

“Although our study is about politicians, we believe it tells us about the wider advantages of a country’s elite.

“So, we’d expect other highly educated and well-paid professions to have similar longer lives.

“Ideally Australia will close this gap by lifting the life expectancy of the general population so that it matches the elite groups.

“Elites likely find it easier, on average, to improve their lifestyle, such as help to quit smoking and being physically active.

“They have more income to spend, for example, on gyms and medication, and possibly get more support from their peers who are on a health drive or are already relatively healthy.”

The authors considered changes in tobacco use and the expanded range of therapies to treat cardiovascular disease as potential explanations for the longevity gap.

For infectious diseases such as Covid-19 that involve person-to-person contact, they said politicians are potentially at a greater risk, as they are likely to experience high rates of population mixing, particularly during election campaigns.

A French study, using data from government elections at the start of the pandemic, did not find “excess mortality in politicians”.

“Beyond transmission, the other key factor that may influence mortality is standard of care, and there may be differentials in the standard of care between politicians and the public,” the authors said.

“For example, in countries such as the United States politicians were some of the first to receive Covid-19 vaccines and the former US President (Donald Trump) received treatment that was estimated to have cost more than half a million US dollars when he contracted Covid-19.”

On the question of whether holding political office directly impacts mortality, the authors said previous studies were mixed.

“A recent analysis of close elections in the US indicates that winners live longer than losers by around a year,” they wrote.

“In contrast, another study involving heads of state from 17 countries found that

winners had a slight survival disadvantage compared with runners-up.

“It is also possible that a selection mechanism (for example, the advent of television broadcasting) changed the type of person who became a politician and this may impact on observed trends.”

Professor Barnett said the study did not look at quality of life: “Some might argue that whilst politicians live longer, who knows if they are happier!”

In 2004, then prime minister John Howard pared back MPs’ retirement benefits, but Canberra’s elite still enjoy more generous superannuation and other perks.

Co-author Philip Clarke, director of Oxford University’s Health Economics Research Centre, said the results show Australia has similar gaps as the other 10 nations between the life-expectancy of politicians and the general public.

“Currently the gap in life expectancy in Australia is around three years which is similar to New Zealand and the UK, but less than half the gap in the US,” Professor Clarke said

“What is surprising in Australia is that unlike the UK, there is much less discussion on how to reduce the health inequalities”.

Professor Clarke, who has an affiliation with the University of Melbourne, said British Prime Minister Boris Johnson has commissioned a review on how to address health disparities, which is central to his government’s “levelling up” agenda, with a white paper due this year.

He said there was value in the Albanese government similarly reviewing the evidence and developing a plan to address these inequalities.

In his election-night victory speech, the Prime Minister said Labor in office would be guided by two principles.

“No one left behind because we should always look after the disadvantaged and the vulnerable,” Mr Albanese said. “But also no one held back, because we should always support aspiration and opportunity.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout