WA juvenile detention system in chaos when youth took his own life

Western Australia’s juvenile detention system had been descending into chaos for three years when Cleveland Dodd, 16, inflicted fatal injuries on himself last October.

Western Australia’s juvenile detention system had been descending into chaos for three years – cells were unliveable, with no running water, and it was common for the young prisoners to riot, escape and self-harm – when Cleveland Dodd, 16, inflicted fatal injuries on himself last October.

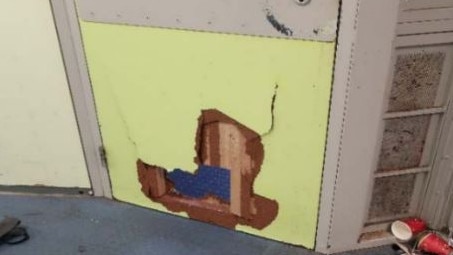

There was outrage in November when it emerged Cleveland had taken his own life in a cell with a hanging point – a broken air vent in the ceiling. All governments had long ago accepted the recommendation of the 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody that a cell with any kind of hanging point could not be used to house a prisoner. However, Cleveland’s inquest was told on Friday that all cells in the high-security unit had some kind of damage.

“No cells were liveable,” said Daniel Torrijos, the guard who found Cleveland unresponsive in his cell in the early hours of October 12. “They were all damaged, everything was damaged.”

Mr Torrijos said detainees had destroyed their cells so many times as rolling lockdowns took their toll. He described a downward spiral at the state’s juvenile detention centre, Banksia Hill, in which shifts requiring 60 staff had only 20. Some good staff had left, he said, because they had been assaulted. There were not enough staff to take the detainees to the onsite school, to onsite football or to do other programs outside their cell. It became routine for detainees to be locked down.

Taps were removed and water switched off in cells because detainees used the taps as weapons. The boys pulled metal plates off walls where the intercom had been, exposing wires, then used the metal plates to dig bricks out of cell walls to escape.

“It got to the stage where it was chaotic,” Mr Torrijos said. “Everything was destroyed.”

Guards invariably used a water cupboard outside each cell to flush toilets but in many cases the boys had destroyed the plumbing and the toilets did not flush at all. Boys had to be taken under guard to an empty cell with a working shower in order to wash.

Cleveland had no access to water in his cell and on two occasions Mr Torrijos said he started a night shift to find day-shift guards had not given him any water. He then had to go to his boss and find two other guards to accompany him to unlock Cleveland’s cell and give him water.

“I wouldn’t feel safe with just two of us,” he said. “(But) Cleveland wasn’t bullshitting, he wasn’t lying. when he said ‘I haven’t got water’. I got permission off the SO (senior officer) and I got the keys and I got him six cups of water.

“That was something I complained about a lot.”

The inquest was told that Mr Torrijos, a father of six, had built a rapport with the boys in the high-security unit, including Cleveland. On one occasion he helped Cleveland write a letter to his father.

On the night Cleveland fatally self-harmed, Mr Torrijos had spoken to him at Cleveland’s request.

Cleveland was a known self-harmer. He had threatened self-harm on eight occasions on the night Mr Torrijos found him unresponsive.

Mr Torrijos told the inquest that on that night, Cleveland was unhappy about having no running water and about a boy in the cell next to his making noise. Cleveland’s neighbour had used the base of his television to hit the wall. He did this for a long time and chiselled his name in the wall.