Australia votes No to the voice: Elites against battlers the great divide

Australians voted according to wealth, education and location, with the Yes vote dying among mums and dads.

Australia split between inner-city elites and the less affluent outer suburbs and regions when they voted on the referendum, with electoral maps showing clearly how the haves backed change and the rest the status quo.

Voter patterns tell a compelling story of how inner-city voters embraced change – including in Anthony Albanese’s seat of Grayndler – in the major eastern seaboard cities but this support bled the further polling booths were from the centre of Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane.

While more than 60 per cent voted No nationally, more than a dozen inner seats in the three eastern capitals returned strong support for constitutional change, also including the Greens seat of Melbourne and the former Liberal strongholds of Kooyong and Higgins in Melbourne.

While some pockets to inner-city seats include low-income workers and pensioners, soaring property prices and high concentrations of tertiary-educated people have transformed these areas, increasingly skewing to the left.

In Brisbane, the three Greens seats of Griffith (56.2 per cent Yes), Brisbane (56.8 per cent Yes) and Ryan (52.2 per cent Yes) returned solid support for the referendum while seven teal seats in the three states voted in favour of change.

In Western Australia, the teal seat of Curtin – in Perth’s inner city – was still likely to vote for change although the Yes margin was down to 50.7 per cent. In South Australia, every seat voted against change but the inner electorate of Adelaide was on a knife-edge, with 49.6 per cent support.

Kos Samaras, director of strategy at the RedBridge Group research company, said the rebuff to Labor in scores of seats showed the party had a significant issue in the way it had communicated the case.

Mr Samaras said Melbourne showed clearest where the problem was – once the inner-city vote was recorded, the support for change collapsed as the distance from the CBD grew.

“Then it just fall off the cliff,’’ he said.

He said Labor had a huge challenge ahead because its messaging was directed at people who were “very comfortable” with the need for change rather than those who needed to be convinced.

Mr Samaras also said the strong support for the Yes vote in seats such as Kooyong, Higgins and Goldstein – which were once Liberal heartland – showed how the electorates were probably lost to the Liberals.

“They’re gone,’’ he said.

Added to the Liberal woes is the entrenched nature of the teals in former conservative seats, including four in Sydney, two in Melbourne and one in Perth.

A senior Liberal strategist said the message from the referendum was that the Coalition’s path to government was less about privilege and more about tradies and struggling mum-and-dad voters.

“The pattern is now so strong that it’s hard to avoid,’’ the strategist said.

The Greens seat of Melbourne voted Yes with a margin of 77.7 per cent, fuelled by wealthy, highly educated people and a large cohort of young voters.

Leader Adam Bandt, despite a thumping “win” in his own seat, slammed the No campaign.

“This outcome follows a Trumpian campaign of misinformation led by Peter Dutton. Peter Dutton’s Liberals ran a corrosive misinformation campaign that fuelled division and fear,’’ Mr Bandt said.

“The referendum campaign clearly demonstrates the need for truth-telling about our history and the impact of colonisation on First Nations people.’’

In Sydney, seats that voted strongly Yes also included Tanya Plibersek’s Sydney (70.1 per cent), Wentworth (62 per cent) and Warringah (58.8 per cent).

But the state overall voted in line with the rest of the country, with just short of 60 per cent voting No.

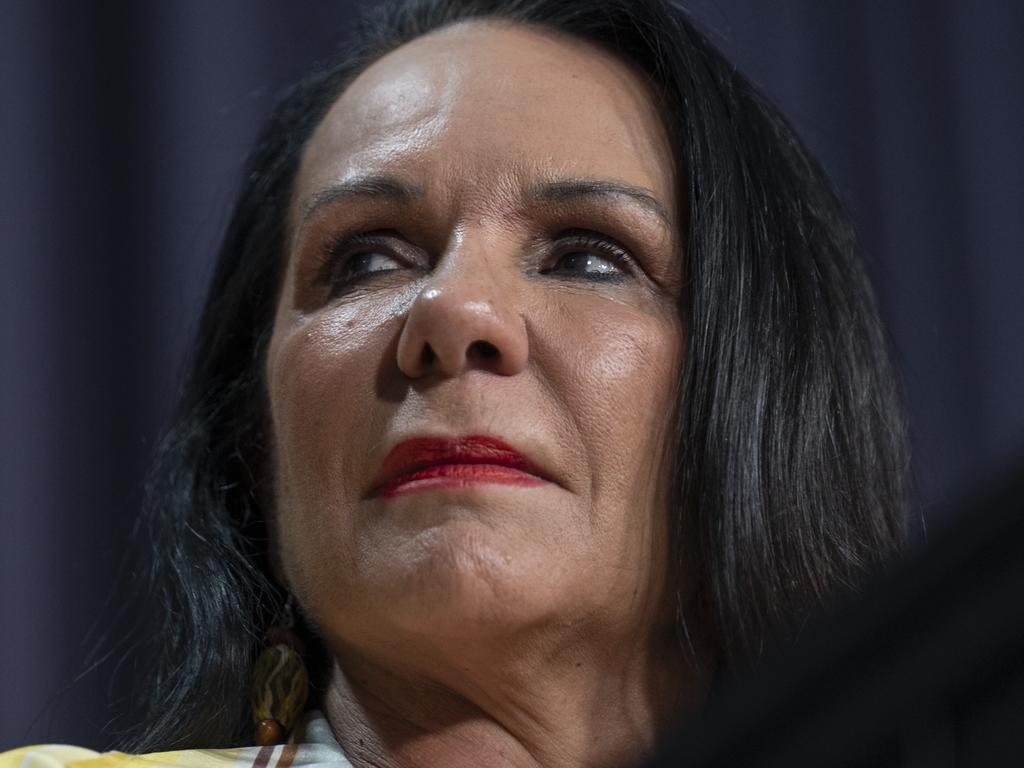

The result was a repudiation of a string of federal ministers, their own electorates voting against the referendum, including Indigenous Australians Minister Linda Burney’s seat of Barton (55.8 per cent No).

In some areas with high Indigenous populations, many voters still opposed change, with nearly 69 per cent of all Queenslanders rejecting reform.

Evan Mulholland, a Victorian state MP, said on polling day there was a clear trend of voters in outer areas, including tradies and ethnic groups, opposing change.

Campaigning in the swing seat of McEwen in Melbourne’s outer northeast, Mr Mulholland said people knew how they wanted to vote.

“People had made up their minds,’’ he said.

The result poses a challenge for Labor in Victoria, with a string of Labor seats in the outer suburbs voting against the Labor-led proposal.

Mr Samaras said there still seemed to be a backlash over the then Andrews government’s Covid-19 lockdown policies, but also that Labor had become less diverse, with heavy emphasis on what party advisers thought rather than what ordinary voters were grappling with.

“It’s activist based or they are staffers,’’ he warned.

Another Labor strategist said the challenge for ALP leaders was in how to capitalise on strong support in the inner-city areas but keep traditional blue-collar workers in the fold.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout