‘This is not ‘green’: battle looming over giant Nullarbor hydrogen hub

A subterranean treasure of ancient caves and lakes beneath the Nullarbor Plain is too precious to lose, scientists say. Can this fragile, hidden world coexist with an enormous renewables hub?

To many, the Nullarbor Plain is a flat and featureless landscape – desolate, sunbaked and windblown. The ideal spot, you might think, to build enormous wind and solar farms far from outraged neighbours and removed from rich agricultural lands and protected mountain ranges.

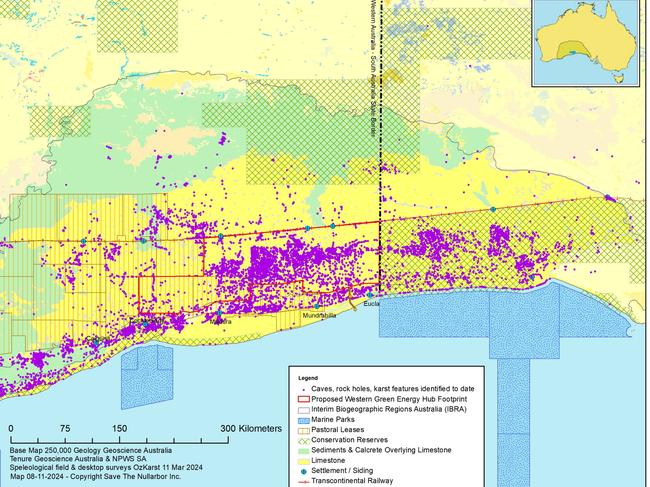

So when a proposal was announced to build one of the world’s largest green hydrogen energy hubs involving 3000 wind turbines and 60 million solar panels across 2.29 million hectares of crown land and pastoral leases in Western Australia’s far southeast, the response was muted.

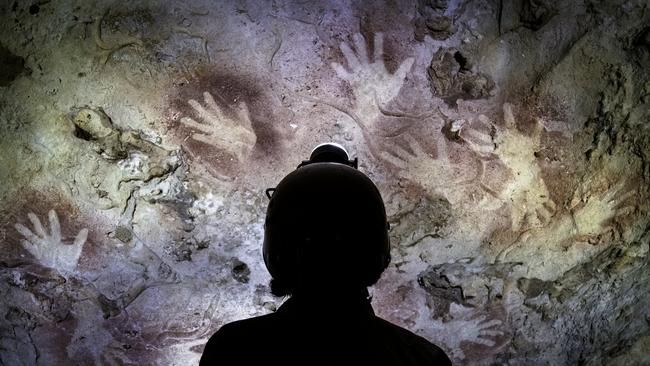

That’s only because most Australians who tackle the two-day drive across the Nullarbor Plain between Adelaide and Perth have no idea of the paradise beneath their car tyres, insists Stefan Eberhard, a cave scientist who has spent 42 years exploring the extensive subterranean network of caves and lakes harbouring fossils, otherworldly creatures and Indigenous rock art.

Laced under the harsh but culturally rich lands of the Mirning people is a time machine reaching back millions of years to the Pliocene epoch, providing scientists with a unique record not just of past environmental events, but clues to our future climate too.

“The Nullarbor Plain is the world’s largest arid limestone karst system, which includes a spectacular hidden world of ancient caves and rock holes of staggering dimensions, beauty, scientific values and priceless cultural importance,” Eberhard says.

“Go ahead and build this energy hub, just don’t do it here in this incredibly important and fragile place. From an environmental perspective it’s the wrong location right on top of the heart of the Nullarbor limestone system.”

Eberhard and wife Bronwen have teamed with scientists to protect the Nullarbor, echoing growing disquiet about the siting of renewables projects in sensitive areas and critical habitat in the eastern and southern states.

These looming battles highlight the problems for state and federal governments racing to decarbonise the economy and meet green energy targets while facing pushback from residents, community groups and scientists over the location of thousands of wind turbines and millions of solar panels with associated batteries, roads and transmission infrastructure.

At full capacity the mammoth Western Green Energy Hub on the Nullarbor, north of Eucla, would produce 3.5 million tonnes of green hydrogen a year targeting domestic and international markets; last year it entered a partnership with South Korea’s biggest electricity utility.

Once complete the developers say the hub will generate more than 200 TWh of renewable energy, “similar in magnitude” to Australia’s current total generation.

“It provides a major opportunity for domestic and international green fuel supply and ultimately domestic power distribution, offsetting approximately 22 million tones of CO2 emissions per year,’’ they say.

The project will include a suite of hydrogen electrolysers, water and hydrogen pipelines, a marine offloading facility and desalination plant along with accommodation for 8000 workers. It’s estimated 27,188ha of land will be cleared.

The Western Australian government said the project would put the state at the forefront of green hydrogen production as demand is expected to soar for use in power generation, shipping fuel, mineral processing and manufacturing.

It’s part of a push to make Australia a global hydrogen leader even as uncertainty remains over the economics of this “fuel of the future”, and three major developers – Origin, Woodside and Fortescue – recently shelved local production plans.

As work progresses on the scoping of the Nullarbor facility, opponents say they can’t stay silent.

“The proposed development is labelled a ‘green energy’ project because it aims to use solar and wind energy to create hydrogen and ammonia; but the project is not ‘green’,’’ Eberhard says.

“It will involve removing vegetation across hundreds of square kilometres of fragile limestone ecosystem, and thousands of kilometres of roads, powerlines, and underground pipelines. The pipelines alone will damage and erode the soils and harm the underground ecosystem, which is the home of rare and unique cave species.”

The effect of this intense industrialisation would be akin to dropping a brick on a meringue, he says. The shallow soils and thin crust that protect the giant limestone karst formations honeycombed under the surface by years of seeping rain are particularly vulnerable to erosion.

The development will take place on the lands of the Mirning people who hold native title rights across the proposed project area.

Mirning Green Energy Limited, a commercial subsidiary of the Mirning Traditional Lands Aboriginal Corporation, holds a 10 per cent shareholding in the hub, alongside developers InterContinental Energy and CWP Global.

Mirning Traditional Lands Aboriginal Corporation said in a social media post the Mirning people will decide whether the project can proceed as part of the Indigenous land use agreement process at a formal community authorisation meeting.

MTLAC will conduct community consultation with the Mirning people before they are asked to vote.

“The caves are a priority for the Mirning people and efforts are being made to avoid them in the proposed project footprint,’’ the corporation said.

The Western Green Energy Hub has also moved to reassure opponents, saying “avoidance of impact” was paramount to respect the environment and safeguard its installations. It says it has carried out location studies to help ensure there will be no physical overlay nor impact on the cave and karst features. Fauna, flora and cultural heritage surveys are ongoing.

“While the project has a large perimeter of land, around 95 per cent of the total project area will remain untouched,’’ a spokesperson said, adding that there was considerable flexibility over where to place the solar panels, wind turbines and related infrastructure.

“WGEH has particularly taken into account those areas that are highly sensitive and protected, and where no WGEH project development will take place.”

However, Eberhard contends that the sheer number of sensitive sites and the interconnected nature of the landscape and groundwater system make it impossible to avoid or mitigate harm.

Beneath the surface an immense aquifer carries water to the Great Australian Bight and the submerged caverns with crystal clear water and extraordinary life forms are vulnerable to contamination, he says.

On the South Australian side, a good part of the Nullarbor is protected in national parks, and Eberhard and his fellow scientists are pushing for the entire site to be recognised as a World Heritage area, pointing to a 1992 report commissioned by the federal government that found the Nullarbor karsts meet World Heritage criteria.

A letter of concern, signed by 20 scientists, was sent to Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek earlier this year in the hope the federal government would intervene to deal with the Nullarbor the same way it saved the Franklin River and the Queensland wet tropics.

Cave scientist Professor David Gillieson, former vice-president of the Australasian Cave and Karst Management Association, said the caving and scientific community was appalled that the development might go ahead.

“The caves have preserved ancient underground landscapes, environmental histories and fauna that have remained ‘frozen in time’ for hundreds of thousands and even millions of years,” he said.

Irrespective of its value for humans, Eberhard says, the Nullarbor should exist undisturbed as a place to experience raw nature, immense space and uninterrupted 360-degree horizon views.

‘We have to understand what could be lost,’’ he said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout