Sydney cleric: ‘Not illegal’ to be mates with convicted jihadis

A Sydney cleric who boasted of his friendship with Islamic State jihadis said it was ‘not illegal’ to be friends with convicted terrorists, spruiking his relationship with ‘brother’ Anjem Choudary, one of Britain’s most notorious extremists.

A radical Sydney cleric who boasted of his friendship with Islamic State jihadis Khaled Sharrouf and Mohamed Elomar said it was “not illegal” to be friends with convicted terrorists, spruiking his relationship with “dear brother” Anjem Choudary, one of Britain’s most notorious extremists.

Wissam Haddad, also known as Abu Ousayd, made the comments in December as he defended legal action brought against him by Australia’s peak Jewish body, which allege he vilified their community in a slew of sermons.

While rejecting he had ever been part of Choudary’s al-Muhajiroun terrorist network, Mr Haddad said it was “not illegal” to “associate, work, or be friends” with Choudary or Omar Bakri, the group’s founder, calling them “brothers of Muslims across the world”.

“Yes, I respect them (Bakri and Choudary), and some of them I know personally, some of them I’ve worked with on seminars, podcasts and lectures,” Mr Haddad said at the weekend.

“It is not illegal to have friends, even though they’ve been convicted with whatever they’ve been convicted with, it doesn’t make you guilty by association.”

Choudary was sentenced to life in Britain in July – a minimum 28-year term – after being convicted of directing terrorist organisation al-Muhajiroun, which emerged in the late 1990s. It has been linked to dozens of acts of terrorism, with followers committing acts of violence in the United Kingdom and around the world.

Choudary has been at the heart of the organisation since its inception and became leader in 2014 after Bakri, whom Haddad has called a “dear brother”, was jailed in Lebanon.

Bakri was released from a six-year custodial sentence in Lebanon in 2023. He had led al-Muhajiroun until its 2004 disbandment – it later operated under multiple fronts – and the British government banned him from returning to the UK in 2005 because his presence was “not conducive to the public good”.

Mr Haddad said he wanted to “make very clear” that he was not part of al-Muhajiroun and that it did not exist in Australia.

“(The group) did exist in the UK, where it was perfectly legal, and they later became a terrorist network, or whatever it is listed as,” he said. “But that has nothing to do with myself.”

Mr Haddad, however, said he had “never denied” knowing “brothers” Choudary or Bakri. “I’ve got nothing to do with al-Muhajiroun, but I’m not distancing myself from other Muslims, and yes (that includes) Bakri and Choudary,” he said, adding that “believers were brothers”.

“Irrespective if you disagree with someone, or if they’ve been charged for a certain thing, or been part of jihadi groups … The fact remains that believers are brothers. Anyone who says that these people (Bakri, Choudary) are not my brothers – who (argue) that they’ve been jailed and convicted – is opposing Allah.”

Mr Haddad said he had been in “contact” with Choudary and Bakri and they were his “brothers in Islam … I’ve never tried to distance myself from these people, but I will continue to distance myself from these organisations … (Bakri, Choudary) are my Muslim brothers, and they are brothers to Muslims all around the world.”

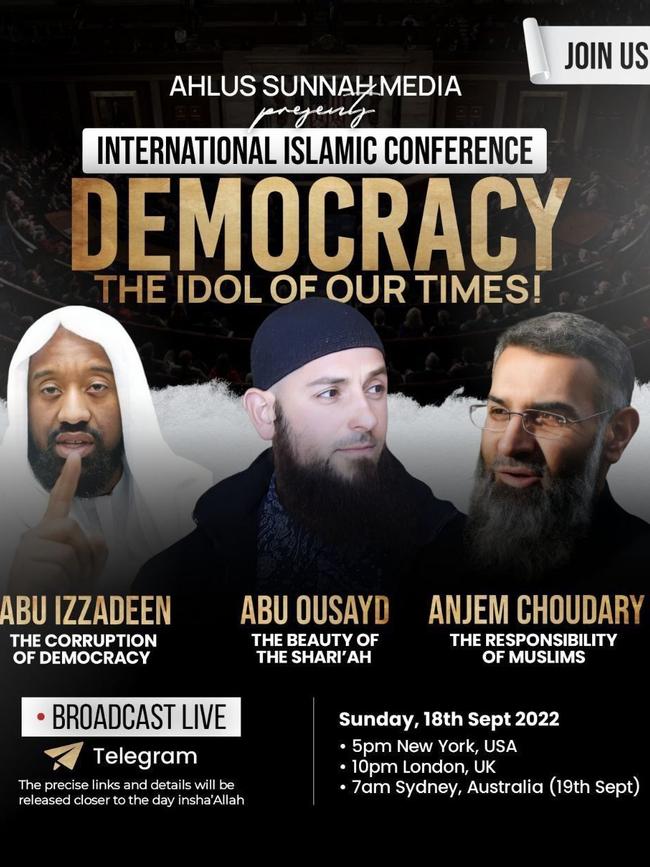

Last year, Bakri provided Mr Haddad with a personalised audio message – referring to him as a “dear brother” – while the Sydney cleric headlined alongside Choudary three “Islam conferences” in 2022.

At Choudary’s July sentencing, a British judge said the terrorist had encouraged members of the al-Muhajiroun network into confrontational street preaching and acts of violence.

“You thinly disguised these exhortations as lessons in Islamic theology,” the judge said. “Organisations such as yours normalise violence in pursuit of an ideological cause. They drive wedges between people who would otherwise live together in peaceful coexistence.”

Mr Haddad has never shied away from spruiking his friendships with known terrorists, and was head of the now-defunct al-Risalah Islamic Centre and bookstore, a hotbed for radical preachers and which was frequented by Sharrouf and Elomar before they fled Australia to join Islamic State in Syria.

In 2016, Mr Haddad said he was still in contact with the pair, showing footage on his phone of them executing Iraqi prisoners.

“(Sharrouf) says he is doing the work of Allah in establishing an Islamic caliphate,’’ Mr Haddad said in 2016. “He is enjoying himself. It is something he has always wanted to do. Why wouldn’t he be happy? He is fulfilling his obligations to Islam.”

Another preacher who lectured at al-Risalah was Abu Sulayman (Mostafa Mahamad Farag), one of Australia’s highest-ranking al-Qa’ida terrorists in Syria.

Mr Haddad closed the centre in 2013, claiming a vendetta by ASIO and the media, before establishing the Al Madina Dawah Centre in southwest Sydney, which has continued to platform extremist preaching.

The centre is also being sued by the Executive Council of Australian Jewry’s leadership, given it allegedly hosted and posted online a raft of sermons from different speakers, including Mr Haddad.

Among other things, Mr Haddad, or speakers at the Al Madina Dawah, have allegedly called Jewish people “descendants of pigs and monkeys”, recited parables about their killing, described them as “treacherous people” with their “hands” in media and business, encouraged jihad, and urged people to “spit” on Israel so Israelis “would drown”.

In most cases, Mr Haddad has claimed he was referring to or reciting Islamic scripture.

The case was brought to the Federal Court by the ECAJ’s deputy president, Robert Goot, and co-chief executive, Peter Wertheim, under section 18c of the Racial Discrimination Act.

At the matter’s first appearance on December 18 in Sydney, the court heard how Mr Haddad’s defence would be filed on February 7 with a provisional four-day hearing set for June 10.

Peter Braham, representing the applicants, said “time was important”, given Mr Haddad’s alleged conduct was in 2023, and he would “robustly challenge” any notion the cleric’s comments “flowed” from established religious material.

Andrew Boe, representing Mr Haddad, said it was “unclear” who actually uploaded the sermons on to the internet and he could call on experts to speak on the “providence” of the comments.