Suburbs where health messages and culture clash head-on

Sheik Azzam Mesto is blunt. Even as Covid numbers increase, it is hard to encourage close-knit families and communities to change how they’ve lived for generations.

Sheik Azzam Mesto is blunt. Having close-knit families and communities change how they have lived for generations was always going to be difficult.

“We have made a lot of sermons, encouraging people to social distance, not visit unless it’s necessary, unless it’s because of compassionate reasons,” he says. “But it’s very hard to change your ways overnight. So you know, there could be less co-operation, generally speaking, because we’re generally people who have a stronger custom.

“And that’s just a little bit harder to break. And it takes time to make those adjustments.”

Overseeing his congregation at Guildford’s Rahma Mosque, Sheik Mesto is at the centre of one of the areas hardest hit by Sydney’s Covid-19 outbreak.

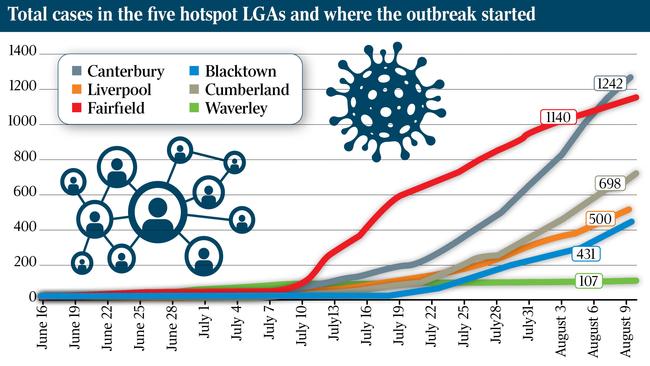

Despite weeks of tight restrictions, the number of cases is not subsiding. On Tuesday, with 234 of the 356 new infections, the city’s west and southwest were again the focal point of the cluster.

And the continuing rise in case numbers is heaping pressure on the NSW government. That much became clear with Health Minister Brad Hazzard’s not-too-subtle attack on ethnic communities on Tuesday. “There are other communities and people from other backgrounds who don’t seem to think that it is necessary to comply with the law,” Mr Hazzard said.

Sydney’s west and southwest have long been a source of frustration for health officials trying to keep the virus in check. There are more language groups, harder-to-reach communities and lower levels of vaccination compared to other parts of the city.

And no public pronouncement was ever going to immediately change behaviours, according to Sheik Mesto. “We are a close culture, with people who visit and care for one another and visit the sick, visit the needy, visit families. We do have large families, obviously. So making the adjustment has been difficult on the collective,” he tells The Australian.

Still, there is an end in sight for the ordeal that has locked down so many of his congregation for weeks. It’s the young.

“The younger ones just want to get back to their lifestyle and freedoms,” Sheik Mesto says.

“From a religious point of view, generally because there is a virus that can kill you, the general consensus is that you should take the vaccine to protect yourself and protect others.”

Sydney’s southwest has one of the lowest Covid-19 vaccination rates in the city, with the latest figures — released on Monday — showing just under 40 per cent of adults have had their first dose.

But that’s up more than 5 per cent in a week, a far quicker pace than other parts of the country.

Ahmad El Naboulsi is one person who is anxious about the vaccine. Mr El Naboulsi’s business — he owns four takeaway shops across the southwest — has been hard hit by the lockdown. Keeping the doors open at Al Fayhaa Halal Chicken in Lakemba is not going to be easy. His friend, in Merrylands, has recently had to close his fried chicken and burger shop.

And yet he is not certain if he will be vaccinated — the one thing Premier Gladys Berejiklian and Mr Hazzard say will return the city to normal and bring back Mr El Naboulsi’s customers.

“I just can’t trust them, I’m not comfortable with (the vaccine),” Mr El Naboulsi — who supports a family of four children aged 18, 15, 12 and 8 — says. “Fifty per cent of the people here are scared, 50 per cent are not,” he said, describing the sentiment among his customers and friends in the area.

“People are taking the vaccine because they have no choice not to. I’m not comfortable with it.”

Others have a different idea. A queue weaves past Mr El Naboulsi’s shop; more than 15 people are lining up for a vaccine at a medical centre two shops down.

Maer Abbas has been friends with Mr El Naboulsi for 12 years.

“He’s an idiot,” Mr Abbas says of his friend when he comes in to the store to order chicken and chips for his family. “Everybody is going to have to take it. The whole world is not going to move without the vaccine.”

The pair argue for the next five minutes as the food is prepared.

“I don’t agree with you, sorry man,” Mr El Naboulsi replies.

Meanwhile, Mohammed Halaby is queuing outside the Lebanese Muslim Association.

He’ll take whatever vaccine he’s given. “It’s really important that you get it, because you don’t know what’s gonna happen next week or the week after or the week after that. If you’re allowed to get it now, next week, you might not be able to get it for a month or two. So you might as well get in, get it quickly to get back to normal,” Mr Halaby says.

He’s not worried about getting the AstraZeneca vaccine.

“Nah. Every day is a risk. (I’m getting the) vaccine shot to help the community as much as we can. Help myself and help the community out, 100 per cent stop the spread.”

Mr Halaby says he doesn’t believe many people are hesitating before lining up for a vaccination.

All his friends have been encouraging him, he says.

“They’re the ones telling me ‘come down and grab it’,” he says.

“Because before we didn’t know how serious it was, now it’s looking serious and whatever can help to stop the spread, man, you have to do it.”