Sting in the tale of $100m tax fraud ‘scoop’

How a veteran news hound stumbled onto the biggest tax fraud in Australian history, only to find himself falsely accused as a key player in the crime – and at the mercy of a serial liar.

On May 17, 2017 Australia was buzzing with the news of the biggest tax fraud in the nation’s history: the $100m-plus Plutus payroll scam, its ringleaders rounded up in a string of co-ordinated raids across Sydney.

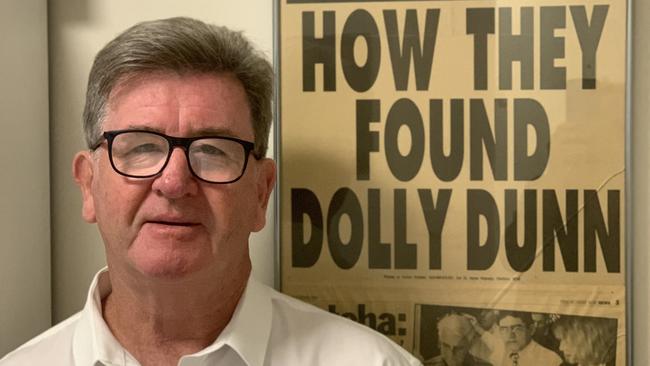

It was the story journalist and crime reporter Steve Barrett had been chasing for months. Even for the legendary “Bar Rat” – a nickname bestowed by an old homicide detective – this would have been the scoop of a lifetime.

But Barrett wasn’t celebrating that morning. He was watching his hard-won exclusive literally disappear before his eyes; the document he was certain would crack the case open now being stuffed into an evidence bag by one of the Australian Federal Police agents ransacking his Frenchs Forest house.

At that point, still dressed in his pyjamas, the veteran journo had no inkling he stood accused of being a key player in the very crime he’d been investigating.

Or that his life was about to be turned upside down, held hostage for the next six years by a serial liar whose romp through the NSW justice system would shame both the police and prosecutors who enabled it.

No, at this moment the Bar Rat was more upset that the expose he’d pitched to A Current Affair was about to become open slather to all.

The story had been perfect for the Channel 9 show: scammers with mountains of cash, luxury homes and racing cars, a former Miss World Australia at their parties and, best of all, a deputy tax commissioner, Michael Cranston, seemingly implicated in – albeit later acquitted of – a mammoth tax scam run by his own son, Adam.

Barrett was furious – and more than a little suspicious about the timing of the raid.

The day before the AFP arrived on his doorstep with a search warrant, the freelance reporter had finally got his hands on what he believed was “the smoking gun” – an affidavit from a NSW Supreme Court civil proceeding that identified the chief perpetrator of the Plutus fraud as none other than Adam Cranston.

“As soon as I read that, I knew I had a goddamn story because that was evidence before a court,” he tells The Weekend Australian. “This was going to turn everything upside down.”

The warrant for the raid had been signed by a magistrate at 5.08pm the day before, suggesting a more last-minute decision than the carefully calibrated raids staged around the rest of Sydney that morning as the Plutus conspirators were hauled in.

Barrett immediately recognised one of the names mentioned in the warrant: Daniel Hausman, a Sydney property developer and the man who only the day before had handed him the affidavit Barrett was convinced would blow the Plutus fraud apart.

But now Plutus had already well and truly exploded, and Barrett, far from landing the scoop of his career, was about to be hit by the shockwave.

The Plutus fraudsters had siphoned off millions in PAYG tax for themselves by contracting out the payroll tax responsibilities of legitimate businesses to second-tier companies run by “straw directors”.

But within the mammoth Plutus tax fraud, another crime was simmering. The Plutus conspirators were being blackmailed by two of their own, Hausman and Daniel Rostankovski, who were threatening to expose the scam.

Police would allege Barrett was a central character in this subplot, brought in to threaten the masterminds with exposure on national television – unless they handed over $5m.

By the end of that day in May, Barrett’s face was all over the news.

Unlike the rest of the alleged conspirators, the reporter already had a public profile. As a 60 Minutes producer, Barrett had famously helped track down notorious pedophile “Dolly” Dunn in South America.

The AFP released a statement falsely claiming Barrett was one of the “straw company” directors – but still didn’t charge him.

A year later, a senior AFP officer informed him, in writing, that he had not been identified as a co-conspirator.

However, at some point over the next 12 months the police changed their mind.

Once again Barrett woke to find AFP officers at his door, one of them the same woman who had earlier reviewed his case and cleared him of involvement.

Now she handed him a summons informing him he was to be charged with extortion.

Stunned, Barrett’s lawyer immediately rang the AFP and asked: Why are you doing this?

The answer he got was: The commonwealth wants it.

Different world

“The Bar Rat” was used to dealing with cops. He’d spent most of his life and all his professional career drinking with them, writing about them, pushing them for tips, sharing their triumphs, commiserating their defeats.

Former 60 Minutes reporter Ray Martin gave evidence for Barrett at the trial.

“I think if you were trying to get someone for central casting who was a crime reporter, you would probably base it on Steve Barrett,” said Martin.

“He’s ethical, he’s accurate, he’s highly respected by his colleagues – which is saying something in journalism.”

When a much younger Steve Barrett started as a police reporter in the late 70s, the Sydney tabloids were at war: the Fairfax-owned The Sun and the Murdoch-owned Daily Mirror competed ruthlessly for big, preferably grisly, crimes to splash across their front pages.

But the world in which The Bar Rat earned his nickname is long gone. His once-talkative police contacts became wary as times changed and police forces around the country introduced media units to break the nexus between investigators and reporters – and control the spin.

Barrett picked up freelance work but he was still doing what he did best – chasing stories.

Panic sets in

By mid-January 2017 the Plutus fraudsters knew the authorities were closing in on them. They were starting to panic.

Two bit-players in the scam, Daniel Hausman and Daniel Rostankovski saw a way to get rich before the whole criminal edifice came tumbling down: blackmail.

On January 27, 2017, Hausman got in touch with Barrett, whom he’d met a couple of times, years before. Hausman told him: “I may have something for you.”

Nothing was ever said about tax or blackmail., or anything remotely like it, Barrett says.

No one will never know exactly what was said in that crucial 8½ -minute conversation because although the AFP had been bugging Hausman’s phone and had recorded hundreds of conversations, they lost that one.

“The most important phone call in all of this case against me, they reckon they can’t find,” Barrett says, shaking his head in disbelief.

He says he didn’t meet Hausman in person until the next day, at a cafe in Newtown, where he was introduced to Rostankowski.

“They started to tell me about Michael Cranston, and his son, and all these battlers, mums and dads, who were getting letters from the deputy commissioner of taxation that they’ve got to pay all these millions of dollars back.”

They told him there would be a meeting involving the Plutus lawyers and Adam Cranston the following week, and that he might be able to get evidence by presenting himself as a journalist concerned about the plight of the straw directors – people he had been led to believe were battlers in caravan parks. “I thought – here’s an opportunity for me to go and shake the tree.”

Barrett pitched the story to A Current Affair’s executive producer, Grant Williams.

“There’s a major scandal in play involving a tax rort and one of the blokes involved is the son of the deputy commissioner of taxation,” Barrett told him. “If I can find out some more about it, would you be interested in doing it on ACA?”

“That’s a pretty stupid question, mate,” Williams told him. “Of course we would.”

Barrett texted Hausman: “If what you say is true, we’ve got a tiger by the tail here.”

To those who know him it sounded like Bar Rat getting excited about a good yarn.

To the eavesdropping police it seemed to show Barrett was eager to play his part in the extortion plot.

The next week, Barrett went with Rostankovski to the scheduled meeting with the Plutus ringleaders in the Martin Place offices of Clamenz Lawyers. Adam Cranston and several other conspirators were sitting around a board table.

Police had already planted a bug in the conference room.

Barrett introduced himself and began a somewhat rambling spiel. “I’ve been a journalist for 39 years in this town and I have been told about an allegation, right, and I want to investigate,” he began.

Hausman would later admit he didn’t want Barrett there when Rostankovski made the blackmail threat, and that he had never told the journalist he planned to blackmail the people in the meeting.

After making his pitch to be let in on the story, Barrett left.

Only then did Rostankovski state his demands.

In the days after the meeting Barrett kept asking for more evidence, but Hausman fobbed him off. Then, three months later, Hausman rang out of the blue.

They met at the Art Gallery of NSW. Hausman opened a folder and took out a Supreme Court affidavit: the “smoking gun” affidavit.

“I was excited because I actually for the first time had a document,” Barrett says now.

He points out that it would have been entirely unnecessary for Hausman to give him the affidavit if he had been one of the criminal conspirators, rather than a journalist looking for evidence.

Hausman also handed him $2000 in cash, which Barrett says was because he had been engaged to start work on getting to the bottom of the affidavit.

Barrett never got a chance to properly look at the document.

The next morning, he was still in his bathrobe when the police knocked on his door.

‘Fraudster and liar’

The court case against Barrett was a shambles.

For many legal observers, the extortion charge seemed nonsensical.

It would have required Barrett to be planning a TV expose – already pitched to A Current Affair and discussed with other journalists – about a crime in which he was an active participant.

It meant Barrett was alleged to have taken part in a $5m scam for which he received $2000 while each of his co-accused trousered $2.5m.

It hinged on the evidence of a single witness, Hausman, who had lied so often that the AFP officers assigned to the case refused to continue taking a statement from him. A witness who had been promised a 25 per cent discount on his jail sentence for giving evidence against Barrett.

The jury never saw AFP reports that showed police knew the Crown’s star witness was a liar.

In an email sent on 28 Aug 2020 team leader Detective Sergeant Morgen Blunden recommended the AFP reject a request by the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions to obtain a statement from Hausman because he “was not a witness of truth”.

Even taking a statement from him “would compromise the credibility and reputation of the AFP”.

Det Sgt Blunden said Hausman was untruthful, unreliable and incoherent and observed that his own lawyer agreed he lacked credibility as a witness.

At the trial the judge ruled the police reports inadmissable because they were “opinion evidence”.

On May 26, 2021, the jury in Barrett’s trial was discharged after it was unable to reach a verdict. But the CDPP was not finished with Barrett, announcing it would seek a retrial.

Barrett is now virtually penniless. He was denied legal aid and had to sell his Sydney home, and dip into his superannuation, to pay more than $500,000 in legal fees.

By contrast, Adam Cranston, the chief architect of the Plutus conspiracy, was given at least $1.2m in legal aid for his defence.

Earlier this month, Barrett filed a last-ditch application for an end to the proceedings, supported by a submission from top silk Greg Woods KC, who agreed to act pro bono.

Allowing Hausman to give evidence would be “an affront to justice” and would bring the administration of the legal system into disrepute, Dr Woods submitted.

“Daniel Hausman is not just a convicted and imprisoned blackmailer, money launderer, fraudster and a liar in general, although he is certainly those things. He is specifically a liar about central issues in the case against Stephen Barrett,” Dr Woods wrote.

Hausman hadn’t just lied in Barrett’s trial. He’d lied again, repeatedly, in the trial of Plutus conspirator Sevag Chalabian in February last year, and in a compulsory Proceeds of Crime examination in May last year. Hausman’s assets had been frozen by an order of the Supreme Court.

But the examination into the whereabouts of money missing from the extortion attempt revealed that Hausman had breached restraining orders by accessing his assets, including cash and property – a criminal enterprise concealed from the court during Barrett’s trial.

Hausman claimed he couldn’t recall how he’d obtained $75,000 to put in a trust account.

The property developer “didn’t realise” he’d transferred his shares in the sale of a valuable Surry Hills property to associates.

He denied a signature was his because “I never use my middle initial” – until confronted with a document he’d signed using his middle initial.

Meanwhile, the CDPP continued to insist Barrett be retried for extortion – in the same court.

The CDPP did not respond to questions from The Weekend Australian about whether prosecutors knew of Hausman’s criminal conduct in the lead-up to Barrett’s trial.

Reputation ruined

Barrett now lives quietly on the NSW central coast, with wife Anne-Marie, relying on social security and handouts from friends. It doesn’t sit well with him.

The stress of the past six years has left him with severe psoriasis. “I’ve got shocking sores all over my body,” he admits.

He does voluntary work with the local Marine Rescue and enjoys it – but it’s not the job he loved for more than four decades. He knows he’ll never get that back. “They’ve destroyed my reputation,” he concedes.

On Friday Barrett returned to the Supreme Court to hear Justice Natalie Adams confirm the news his lawyer had given him earlier in the week.

The CDPP was giving up the case. After six years it had agreed to drop the proceedings.

It was a rare moment of joy, or perhaps simply relief. But it wasn’t what Barrett most wanted: a finding of not guilty.

Because, he says, it could all have been avoided.

“For Christ’s sake, I was a journalist for 40 years, they knew who I was – why didn’t they just come and talk to me?”