Sofronoff findings on DPP Shane Drumgold to be kept secret for weeks

Chief prosecutor Shane Drumgold is in the firing line — but in a suprise move the ACT government won’t release the Sofronoff report for at least a month.

In a shock move, the ACT government will keep secret the findings of the Sofronoff inquiry into the prosecution for rape of Bruce Lehrmann for at least a month as it ponders how to deal with what are expected to be serious adverse findings against chief prosecutor Shane Drumgold.

It had been anticipated that when inquiry head Walter Sofronoff KC delivered his much-anticipated report on Monday, it would be released immediately but the government will now consider the report “through a proper cabinet” process that ACT Chief Minister Andrew Barr said would take three to four weeks, with the Legislative Assembly “updated” at the end of August.

It is believed at least two of the potential findings against Mr Drumgold, who has been on leave since May and is not due to return until August 30, would be grounds for his dismissal as ACT Director of Public Prosecutions.

In a statement released to The Weekend Australian, Mr Barr said that subject to the contents of the report, and any legal implications, he intended to table all, or part, of the report during the August parliamentary sitting and “may provide an interim response to some, or all, of the recommendations” at that time.

“Subject to the recommendations, a final government response may take several months,” he said.

The most serious allegations of misconduct against Mr Drumgold involve episodes where he misled Chief Justice Lucy McCallum during the course of the proceedings against Mr Lehrmann.

Mr Drumgold has already admitted two breaches but claimed they were unintentional.

If Mr Sofronoff finds his actions were designed to deliberately mislead the court, his position as DPP will be untenable.

Even without findings of serious misconduct against him, legal observers say it is difficult to see how the ACT criminal justice system can function effectively with Mr Drumgold at the helm.

The relationship between Mr Drumgold and ACT Policing, already poisoned during the Lehrmann prosecution, has been further damaged by claims and counter-claims in the inquiry.

Mr Sofronoff is likely to find Mr Drumgold was entitled to bring the prosecution against Mr Lehrmann – none of the parties to the case, including the police, has disputed that – but both the DPP and some senior police may be found to have lost objectivity at various points in the case.

Mr Drumgold conceded at the inquiry that he had formed a view Mr Lehrmann should be charged before he had been interviewed.

The AFP and some senior officers are also likely to come in for trenchant criticism from Mr Sofronoff over the handling of aspects of the case but none is expected to lose their job.

Victims of Crime Commissioner Heidi Yates may be the subject of some criticism over claims her constant presence at Brittany Higgins’s side during the trial was effectively a declaration that the young woman was a victim of crime and that Mr Lehrmann must therefore be guilty.

However, the police walked back much of their earlier criticism of Ms Yates during the inquiry and Mr Sofronoff may look towards recommendations such as a suggestion he raised during the hearings that her title be changed to “complainants of crime commissioner” to avoid any inference of guilt.

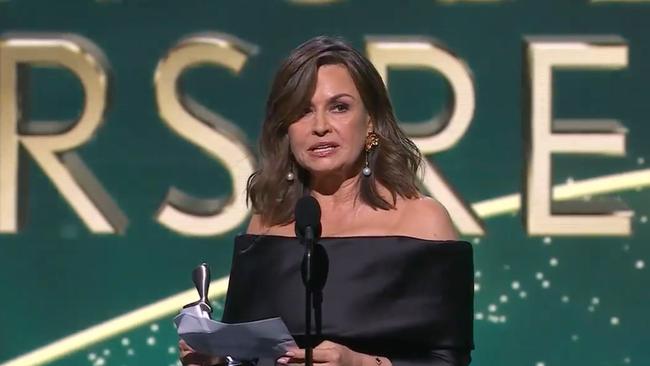

Possibly the most serious allegation against Mr Drumgold relates to a so-called contemporaneous note made of the now-infamous conference he held with TV personality Lisa Wilkinson four days before her Logies speech.

He says he warned the then-The Project host about the danger of prejudicing Mr Lehrmann’s upcoming rape trial. Wilkinson rejects that, saying Mr Drumgold “did not at any time” give her the warning he claimed.

Mr Sofronoff may take the view that while the experienced journalist should have known better, Mr Drumgold could have been more proactive in warning that the speech would risk delaying the trial by several months – which is what then occurred.

Far more dangerous for Mr Drumgold is the note of the conference with Wilkinson, which the DPP presented to Chief Justice McCallum as if it had been written contemporaneously by a junior lawyer present at the meeting. It hadn’t. It was effectively written by Mr Drumgold days later after Wilkinson gave her speech.

At the inquiry, Mr Sofronoff questioned Mr Drumgold’s concession that his submissions to the Chief Justice “could” have had the effect of misleading her. “It must have had the effect of causing Her Honour to think that the note was a contemporary note of the conference,” Mr Sofronoff said.

“How could it not have had that effect, having regard to the appearance of the document, and the absence of anything that would suggest that part of it was made five days later?”

A finding by Mr Sofronoff that Mr Drumgold failed to appropriately warn an experienced journalist of risks posed by the Logies speech might be survivable for the DPP; a finding he deceived the Chief Justice would not.

The second major threat to Mr Drumgold’s job comes from the so-called Moller report, first revealed by The Australian, part of which detailed discrepancies in Ms Higgins’s evidence and suggested police didn’t think there was enough evidence to prosecute Mr Lehrmann.

Mr Drumgold tried to stop the defence obtaining the document, claiming it was subject to legal professional privilege – without having read it and without checking with Detective Superintendent Scott Moller, who wrote it.

That goes against basic principles of a prosecutor’s duties of disclosure, which require any relevant evidence, particularly matters adverse to their case, must be revealed to the defence.

Mr Sofronoff made no secret of his alarm at Mr Drumgold’s approach, asking at one point: “You could not possibly, as a barrister, say ‘I’m prepared to give an opinion about this’ without proof from the man who made the document, could you? You would need some facts. And you don’t seem to have any facts, Mr Drumgold.”

Mr Drumgold also ordered the same junior lawyer, barely six months into his legal career, to draw up an affidavit saying the document had been inadvertently listed as not subject to privilege.

This too was unintentional, Mr Drumgold told the inquiry. But again, a finding that he deliberately misled Chief Justice McCallum would make it near impossible for him to remain in office.

Mr Sofronoff could also make adverse findings about Mr Drumgold’s conduct when he announced in December that he was abandoning the trial out of concern for Ms Higgins’s mental health but suggested he still believed Mr Lehrmann was guilty.

The speech left many in the legal profession aghast.

Counsel assisting the inquiry Erin Longbottom asked Mr Drumgold: “Did you turn your mind to the impact that statement might have on Mr Lehrmann, who was entitled to the presumption of innocence?”

“Possibly not as much as I should have,” Mr Drumgold replied.

Similarly, Mr Sofronoff is expected to make a finding on allegations Mr Drumgold improperly attempted to discredit former defence minister Linda Reynolds during cross-examination when she appeared as a trial witness.

Mr Drumgold questioned Senator Reynolds about the presence of her partner in the court, even though no one had suggested there was anything wrong with this, and about a text message she sent to Mr Lehrmann’s defence counsel requesting a transcript of the trial.

At the inquiry, Mr Drumgold sensationally retracted his claim of political interference in the case.

A finding by Mr Sofronoff that the cross examination was improper would be controversial because by rights Chief Justice McCallum herself could have intervened to stop the line of questioning. It is not within Mr Sofronoff’s terms of reference to examine the conduct of the Chief Justice.

The Australian Federal Police and some senior officers are unlikely to escape censure.

The AFP was confronted during the hearings with claims it was applying the wrong test to charge sexual assault suspects and that, as a result, the ACT had some of the lowest rates of charging (and conviction) of sexual assaults cases in the country.

Police admitted they made a grave error in providing Ms Higgins confidential counselling notes to a defence lawyer, but said it had been done accidentally.

That lawyer did not access the sensitive documents, but Mr Drumgold did.

AFP officers were also alleged to have conducted an unnecessary formal interview with Victims of Crime Commissioner Heidi Yates so that she would become a potential witness and therefore would not be able to support Ms Higgins in court.

The inquiry heard that police only charged Mr Lehrmann after receiving a phone call from Ms Higgins’ boyfriend, David Sharaz, threatening to publicly condemn the time being taken.

Detective Superintendent Scott Moller said that within an hour of Mr Sharaz calling Detective Inspector Marcus Boorman, he was given instructions to serve a summons on Mr Lehrmann for one count of sexual intercourse without consent.

Superintendent Moller said his investigators did not believe they had met the evidentiary threshold to charge Mr Lehrmann so he signed the summons himself.