Skilled migrant cap stifles economy: KPMG analysis

Ramping up net migration levels to 350,000 a year would boost the economy by $120bn, new analysis reveals.

Ramping up net migration levels to 350,000 a year to make up for the collapse in overseas arrivals during the pandemic would boost the economy by an extra $120bn and raise GDP by 4.4 per cent by the end of the decade, exclusive KPMG analysis reveals.

As business groups demand for the annual cap on permanent skilled migration to be lifted from 160,000 people to 200,000, KPMG chief economist Brendan Rynne argued the nation would be better served by adopting a more aggressive approach to attracting migrants over the 2020s.

Dr Rynne said net overseas migration added 10 per cent to the size of the population over the decade to 2019, and that the federal government should be targeting a similar contribution over the 10 years to 2029.

If Australia wanted to match the same 10 per cent growth in population through international migration, then net overseas migration would need to total about 2.56 million between 2020 and 2029.

But ahead of a federal election that must be held by May, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg has flagged the government has no intention of rolling out more aggressive net migration targets.

Instead, the Morrison government’s focus remains on opening the country back up to overseas arrivals as quickly and safely as possible – a task complicated by the explosion of Omicron cases.

Anthony Albanese has made no sign his party supports a “Big Australia” policy, let alone an even bigger population of the sort supported by economists such as Dr Rynne and employer groups.

The Opposition Leader has instead articulated an “Australians first” approach to filling job vacancies, which sit at 13-year highs, and warned that the nation is overly reliant on temporary migration. Employment Minister Stuart Robert has expressed similar sentiments, saying locals must be given the “first crack” at plugging labour gaps created by the pandemic.

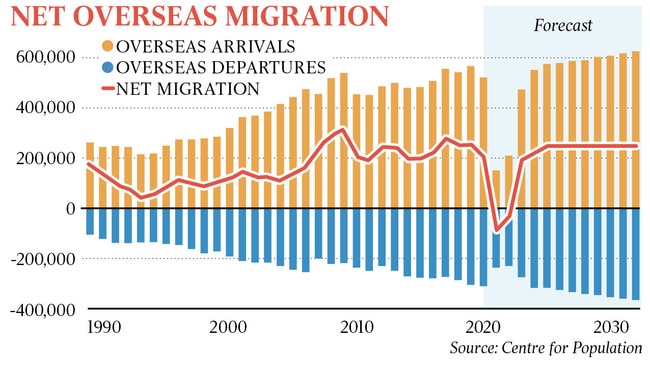

Centre for Population forecasts, released just before Christmas, have suggested net overseas migration would remain negative this financial year, with a net drop of 40,000 people before slowly recovering to 235,000 a year from 2024-25 to the end of the projection period, 2031-32.

Based on these official forecasts, net migration would boost Australia’s population by 1.63 million people over the 10 years to 2029 – 540,000 fewer than in the preceding decade, and 900,000 less than required to match the 10 per cent population contribution.

The KPMG analysis shows Australia would need to increase its net migration levels by about 50 per cent versus the Population Statement forecasts in order to match the decade to 2019.

Dr Rynne recognised that substantially ramping up net migration levels to 350,000 people a year from now until 2029 seemed like “a lot”, but he argued that a Bigger Australia approach was ultimately in the national interest.

Not only would real GDP be 4.4 per cent larger by the end of the decade, but investment, exports and consumption would all be greater as would output on a per capita basis.

“I am absolutely a supporter of increasing migration to Australia and at levels above what is in the Population Statement to ensure not only that we get the economic benefits, (but also) the social and cultural benefits you get from opening your borders and allowing a truly multicultural society,” Dr Rynne said.

The only key economic variable negatively correlated with higher migration levels was real – or after inflation – wages.

Dr Rynne said the “first order” impact of higher population growth was to increase the supply of workers, “which is a moderating factor on wages”.

But he said “the second-round benefits, particularly from skilled workers who bring greater productivity, is that this productivity improvement is the thing that generates sustainable long-term wage rises”.

Brendan Coates, the head of the Grattan Institute’s economic policy program, said the national debates about migration policy “tend to focus too much on the size of the intake and not enough on who we choose”.

“Who comes matters as much, if not more, than the number of migrants that do come,” Dr Coates said.

“Migrants, especially skilled migrants, boost Australian GDP per person.

“Yet migrants, who have tended to be higher skilled capture much of the increase in GDP themselves via their incomes. The big benefit from migration, especially skilled migration, is the fiscal dividend they generate for the Australian community because they pay more in taxes than they receive in public services and benefits over their lifetimes.”

Dr Coates cited recent Treasury analysis that showed that the average permanent migrant provided a fiscal dividend of $41,000 over their lifetime since they paid more in tax than they received in publicly funded services.

Skilled workers, however, provided a much larger fiscal dividend, according to Treasury, with the typical migrant sponsored by their employer giving a lifetime fiscal dividend of $557,000 “since they are younger, earn higher incomes, and pay more in taxes”, Dr Coates said.

Dr Rynne agreed that higher migration – particularly skilled workers coming to Australia “in the prime of their lives” – would help address the daunting challenge of bringing down the massive deficits and debts incurred through the pandemic.

He said that eventually there would be population “tipping points” where the costs from more people began to outweigh the benefits, but that this was still some way off.

“Our population density is still so low,” Dr Rynne said.

“We have the majority of people living in our major cities and what we haven’t started to develop is satellite regional cities like they do in America, in places like western Sydney, Geelong, on the Sunshine and Gold Coast and even inland cities that can grow even stronger, like Toowoomba.”

Dr Rynne said “the cost of a larger population relates to congestion, an overburdening of the health and education systems”.

“But what Covid has enabled us to do is work very differently, and so the likelihood of per capita costs associated with migration are likely to be smaller,” he said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout