She’s 78 with her share of health problems, but there will be no retirement for Cambodian charity mum Geraldine Cox

Renowned humanitarian Geraldine Cox, 78, has been showered with almost every honour open to Australian citizens, except the one she really wants. An aged pension.

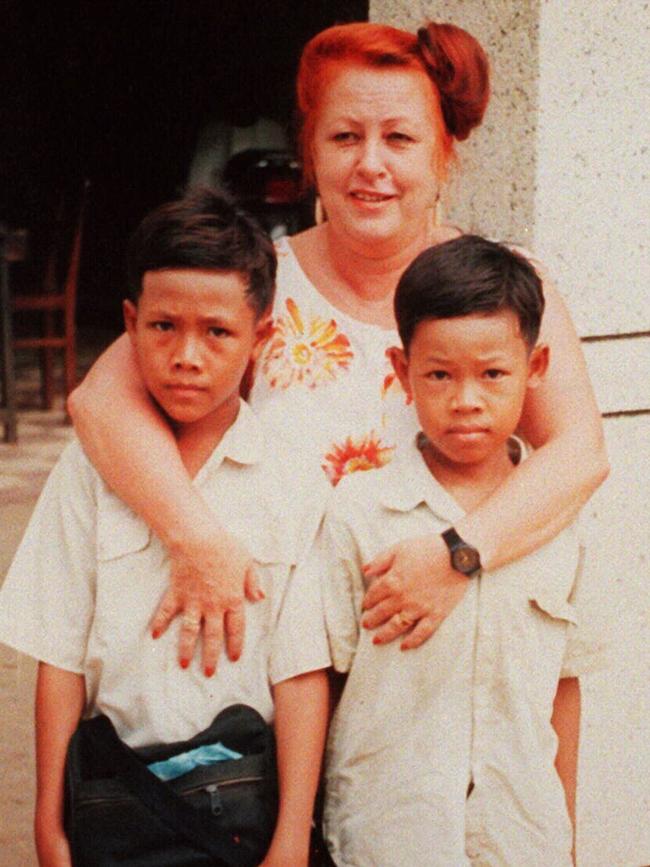

Geraldine Cox is standing barefoot on a stage surrounded by Cambodian children proudly waving their achievement certificates for the school photographer. Dressed in a boldly patterned frock in the December heat, her flame-red hair pulled into her trademark top knot, Cox chats with the kids and enfolds them in spontaneous hugs, smiling through the throb of a recently stubbed toe.

This legendary Australian, known as much for her no-bullshit candour as her humanitarian work, doesn’t like limping around. She hates that she can no longer sit on the ground with the kids at the local temple and has to accept the monks’ offer of a chair instead. With a wry grin she reveals that it’s not unknown for her to head off to town with her removable prosthetic boobs, a legacy of a double mastectomy, pointing in the wrong direction.

“I am beginning to drag my feet a bit even though I don’t want to admit it,’’ she says.

Old age is a particular inconvenience for this energetic 78-year-old who has devoted 30 years to abandoned and abused children in Cambodia while battling through a military coup, cancer, fundraising challenges and changing public attitudes towards westerners running orphanages in developing countries.

“Orphanage is now an unacceptable word,’’ she says with a look that conveys exactly what she thinks of this encroachment on plain speech. “You now have to say residential care for children at risk,” she sighs.

Cox is a realist – decades living in one of the poorest countries in the world teaches you that – and with the march of time came the hard fact that she needed a successor for her Sunrise Cambodia organisation, which provides a home for about 60 children and day school for some 200 poor village kids.

The life force behind the charity, she couldn’t simply walk away. She would continue as a figurehead and mum to the residential kids while handing over the daily operations to a younger, hand-picked recruit, former Australian journalist Tracey Shelton, last October.

As Cox planned for her retirement years she sent off her application for the old age pension. Though granted Cambodian citizenship by royal decree in 1999, she remains a proud and well-known Australian. She thought she would qualify for benefits. In expat enclaves around Cambodia and other southeast Asian countries, Australian retirees while away their days on regular pension payments that buy a level of comfort they’d never afford at home.

Australia has bestowed many honours on Cox for her Cambodian work: an Order of Australia in 2000, the federal government’s Centenary Medal for service to the welfare of children in Cambodia in 2001.

In 2009 she was the “orphanage mother’’ finalist for the South Australian of the Year and two years later was awarded the Sir Edward “Weary” Dunlop medal which recognises individuals committed to enhancing Australia-Asia relations.

‘Disappointed’

Cox still visits Australia three or four times a year; many of her charity’s donors are here, and her profoundly disabled adopted daughter Lisa is in full-time care in her home state of South Australia.

She is, in all but address, Australian, so she was surprised when her pension claim was knocked back because the rules require applicants to be in the country at the time of making the claim and then remain resident for two years before the pension becomes portable.

“I can’t live in Australia,’’ Cox says bluntly. “Firstly, I wouldn’t leave my kids for two years and, secondly, I have nowhere to live in Australia.’’

Cox says she can’t just lob up to her older sister’s place in South Australia. “My sister, my only close relative, is old and sick and does not have a spare bedroom and certainly could not support me.’’

She shares with Shelton a home built on the grounds of Sunrise, land gifted by former Khmer Rouge commander turned Cambodian strongman prime minister Hun Sen, a remarkable act given she once publicly described him as “a murderer and a gangster – no better than Pol Pot”.

In her retirement, Cox planned to continue fundraising duties but didn’t want to draw a salary from the hard-won funds. “I was relying on getting the old-age pension to survive and continue living with the children here. Normally it’s not my wish to be treated differently to anyone else but, without sounding righteous, I feel like I’ve got a case,’’ she says.

In an email plea to Social Services Minister Amanda Rishworth’s office, Cox pointed to her 18 years’ service with Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs in embassies in Cambodia, The Philippines, Thailand, Iran and the US. It was a colourful career, as detailed in her revealing 2000 memoir Home is Where the Heart Is. “I wasn’t a very good public servant,’’ she admits.

She’s never claimed benefits and says she paid tax from 1960 until 1995 when she moved to Cambodia.

Earlier this month, Cox was informed that her appeal for a review had failed. The rules are set in legislation, the government says, with no room for ministerial discretion.

“You have not been an Australian resident from 12 October 1995. As you were not an Australian resident when you lodged your claim, you cannot be granted age pension,’’ the review said.

She shakes her head and sighs: “I’m very disappointed with the Australian government.”

Setbacks

Cox is used to navigating the hills and valleys of life, as she likes to put it. The milkman’s daughter from Adelaide who left school at 15 has had her share of setbacks in a wild life of adventure, but the past few years have tested her.

Her charity began as a home for the battle-worn country’s orphaned and vulnerable children but by 2011 an explosion in Cambodian orphanages led to concerns that some centres were exploiting the very children they purported to care for. Homes that were poorly run, profiting from children who were not in fact orphans and facilitating abuse of their vulnerable wards cast a shadow over all the charitable programs. Across the world, the word orphanage, with its baggage of institutionalisation, acquired a particular stench.

By 2017, Australian politicians and activists were agitating for legislation banning Australians from supporting or volunteering in overseas orphanages. “It was one of worst periods of my life,’’ Cox says, breaking off our conversation to arrange a medical appointment for a former Sunrise resident. “We don’t give money to past kids, but we will give her rice, kitchen items and pay for her medical care and any operation she may need,’’ she explains.

She agrees that there were poorly run centres with appalling practices that had to be shut down. Sunrise was never caught up in wrongdoing, is registered by and works with the Cambodian government and undergoes regular inspections.

But a cloud settled over all orphanages. Ambassadors stopped visiting and donations took a hit even before Covid struck a further blow. Cox restructured her charity, scaled back the residential aspect and expanded educational and community outreach programs. Some services were closed, including one home for HIV children.

“In 2016, UNICEF said there should be no centres exclusively for HIV kids, you have to put them back in the community so we had to put 70 kids back into the community. Three of them died because the family didn’t give them medicine. We send them their drugs every month but some families just don’t give it to them.”

She accepts the new status quo, the need to transition children back to family or kin or foster care when it’s safe, and to concentrate efforts on community education and development. But she argues that some of her kids, particularly the disabled youngsters who require round the clock support, have nowhere to go and will be there for life.

“We’re trying not to take any more residential children unless it’s a severe case,’’ Cox says, but then reels off examples of children seized from begging rings or factories, or the government asking her to take abused children. A rescued three-day-old baby recently arrived and three children seized from slave-like conditions in a brick factory are due soon.

She tells of 15 children abandoned in hospitals when they were babies. “There is no way we can find these kids’ families and they are our most emotionally damaged kids.’’

Some children do have families that are welcome to visit. And if the child can be returned safely to their family, and wishes to go, reunification is facilitated.

Cox has high hopes for every child here and lists the Sunrise kids who have gone on to university, pointing out that no one leaves at the age of 18 without a university scholarship, vocational training or a job.

“She lives and breathes the kids’ lives,’’ says board director Hugh Darwell, an accountant and business development executive based in Phnom Penh. He has just wrapped up the latest audit and notes that donations were down by about half, amounting to $US400,000. Some recent bequests from the US will bump things up and Australians have traditionally strongly responded to Cox when things get desperate: in 2020, when donations took a hit during Covid, viewers of A Current Affair donated more than $600,000 after a segment on the charity’s plight.

“It’s a month-to-month existence,’’ Darwell says now. “We do have some reserves that we draw on, but we definitely need the constant flow of cash.’’

So retirement is on hold as Cox throws herself into full-time fundraising, chasing down larger corporate donations, staff giving programs and $50 a month individual sponsorships.

She takes me around the centre outside Phnom Penh, introduces the children who run up to give her a hug. It’s these kids that get her up every day – the thought of running out of money and having to close down brings her to tears. Cox has 40 staff here, all Khmers apart from herself and Shelton. There are teachers and housemothers, cooks and groundsmen all relying on her for jobs. Without a pension she remains on staff, drawing a salary of $2000 per month, exactly what she didn’t want to do.

Shortly she’ll be back at her desk, writing proposals, cold calling businesses and old contacts, knocking on doors, looking for a foot in. She’s persuasive and relentless with a drive that hasn’t abated with the years. In her spare time she tries to find time to write her second book. Its working title? I Am Still Here.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout