Rolf Harris, dead at 93, was a sexual predator in plain sight

The enormous popularity Rolf Harris enjoyed as an entertainer gave cover for his attacks on young girls and women for years until his crimes were exposed.

It was at Southwark Crown Court in central London in 2014 when Rolf Harris’s illustrious career came crashing down. The high-profile entertainer, artist and children’s show favourite was unveiled as a serial predator of young girls and women, having used his fame and his self-acknowledged “I’m a cuddler” schtick as cover to prey on innocent and vulnerable young girls and teenagers, often in very public places.

A previously adoring British and Australian public was horrified when Harris, the quintessential Aussie entertainer – who led the way for others, from Olivia Newton-John to Steve Irwin, to proudly flaunt Australianness to the world – was so disgraced he was sentenced to five years and nine months’ jail for 12 counts of indecent assault against four women across several decades.

No longer the endearing patriotic Australian expat with a true-blue persona, Harris was now a vile multiple sex offender.

Seven women, one who had been seven, had testified in weeks of harrowing detail that he sexually assaulted them during their childhood or mid-teens.

“Out of nowhere his hand came down my back and between my legs,” one woman recalled, adding that Harris continued cheerfully signing autographs as she walked away.

A 16-year-old spoke of the assault as being “humiliating, degrading and awful. And your blood turns to concrete”, and noted that Harris leered triumphantly and free of remorse.

Harris’s methods – quick, painful and shocking – were shown to be very similar despite the offences occurring decades apart and in different countries, from the US to Australia and Britain.

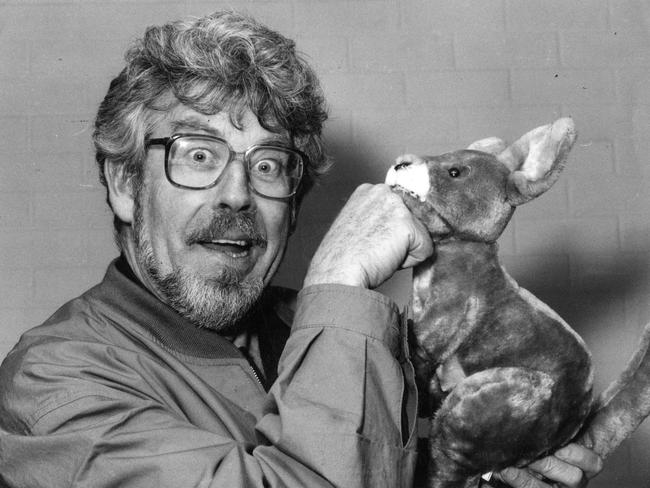

And all throughout it was Harris’s quirkiness and enormous popularity, sparked by ditties mixing the sounds of Aboriginal music (he popularised the didgeridoo and clapping sticks) with catchy melodies, suitable-for-children lyrics and his own innovations such as the wobbleboard, that provided an impervious cover for his attacks on girls throughout the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s.

After the first conviction, the British Metropolitan Police prepared a brief of evidence of another 20 women who experienced Harris’s “octopus hands” and physical abuse under their clothes.

Harris was still abusing aged in his 70s, police believe.

Ultimately he would face a second trial involving seven women, including one blind and disabled woman, but that was dismissed when Harris was acquitted on three of the charges. In a retrial the jury was unable to reach verdicts.

Harris’s abuse of young or vulnerable women was uncovered only after the Met police opened a special investigation looking at historic sex claims under Operation Yewtree in the wake of how another pedophile, the weird entertainer Jimmy Savile, had avoided scrutiny until after his death.

While Savile, who also had a prime-time television show like Harris, would be found to have abused 500 young women, including psychiatric and hospital patients, Harris’s dark side was uncovered only after a friend of his daughter Bindi had come forward in 2013.

This friend was first abused by Harris when she was 13, and a key part of the prosecution was that Harris had handwritten an apologetic letter to her father admitting to being sickened by his behaviour and the emotional damage he had inflicted, but insisting he hadn’t begun a relationship with her until she was 18.

“I fondly imagined that everything that had taken place had progressed from a feeling of love and friendship – there was no rape, no physical forcing, brutality or beating that took place,” Harris had written.

Incredibly, in 1985, when Harris was now known to be offending, he also was fronting an anti-child abuse campaign, encouraging children to tell a trusted adult about anything that was happening to them. The Kids Can Say No! about sexual abuse led to Harris addressing an international child abuse congress in Sydney months later.

For this was at the height of Harris’s career, which had began at London’s Down Under Club in 1957, a haven for homesick Australians, and the venue where Harris first performed Tie Me Kangaroo Down, Sport.

Harris even turned his large-canvas, high-speed paintings into performance art. He often would be branded a “professional Australian” – a label that, understandably, left him cold. “I’m a professional ‘self’,” he said, “and being Australian is just part and parcel of being me!”

Born in the Perth suburb of Bassendean on March 30, 1930, the young Harris was always blissfully uncertain of his future. “I would try to avoid being seen with him,” his older brother Bruce Harris recalled, “because he’d be walking down the street on his hands, or singing loudly, or whistling, and I would want to disappear.”

If Rolf Harris seemed destined for fame, it was at first in another area: swimming. As a 15-year-old he was the Australian junior backstroke champion. During the next few years he became West Australian champion in most swimming styles until he suffered a serious ear infection. He also showed promise as an entertainer, winning the Amateur Hour radio show at age 17, and playing piano, rather poorly, for his own three-piece band.

He trained (half-heartedly) to be a teacher but soon decided he was ill-suited for the job. In 1952, and with a certificate from teachers training college, he went to London to study one of his more passionate interests: painting.

In this he showed promise. Within a few years some of his watercolours and oil paintings were accepted into the Royal Academy’s summer exhibition. His quick-sketching prowess also had won him some work on children’s TV as a regular on the variety show Whirligig, illustrating the adventures of a boy named Willoughby on live television. He also appeared in films such as You Lucky People (1955) and TV shows such as Hancock’s Half Hour.

Returning home, he unleashed Tie Me Kangaroo Down, Sport on TV audiences through a Perth variety show and it was a worldwide hit. The Germans translated it into a romantic tear-jerker; a French-Canadian version spoke not of kangaroos but of a woman’s agony over her sex-mad boyfriend. In English, it would be recorded by unlikely artists such as Pat Boone, Ray Conniff, the Wiggles and even the Beatles (in a BBC session).

Moreover, it became Harris’s signature song, still included in his concerts 25 years later. “You don’t get sick of a song that has taken you around the world 19 times,” he said in 1978. But while he was proud of the song’s success, he also was somewhat perplexed. He had written it on the back of a menu in a London restaurant to occupy his mind as he awaited a prospective father-in-law, intending to ask for permission to marry his daughter.

“I thought the words were great and I showed them to him,” he recalled. “He is a very pukka gentleman and he thought they sounded like a load of old rubbish.”

The marriage to sculptor and jeweller Alwen Hughes still went ahead. “I should go back and point out to him that that load of old rubbish has taken his daughter 19 times around the world, too.” Hughes, who suffers from Alzheimer’s disease, was a staunch supporter of Harris throughout his rollercoaster life.

Harris had more hits, of course, including the Christmas song Six White Boomers (1960); Sun Arise (1961), which borrowed some of the style (and the instruments) of Aboriginal music; Court of King Caractacus (1964); and Jake the Peg (1966), originally a 150-year-old Dutch song, which he would perform onstage with his own, self-constructed extra leg.

In the Southwark court he even provided a short rendition of Jake the Peg for the jury as he gave a rundown of his career.

In 1967, he was a last-minute replacement for singer Vicky Carr, who had taken ill, for a short series of Saturday night BBC variety shows. The Rolf Harris Show, in which he basically repeated his stage routines, won more than 15 million viewers and led to a three-year contract.

Musically, Harris extended his range in 1969 with the powerful Two Little Boys, often wrongly assumed to be about the Australian Light Horse Regiment of World War I. It was actually composed in 1903 and set in the US civil war. Harris’s version, however, became the definitive one.

At one London charity event, a woman in the audience called out: “Sing the one about the two little boys. It’s the only one of yours I’ve liked.” His response was: “Shall I tell them the only thing of yours I’ve liked?”

While Australians tend to grow weary of their familiar celebrities, British audiences remain loyal and Harris’s TV career continued to blossom. Along with his TV shows, he began a long-running series of television advertisements (“Trust British Paints? Sure can”).

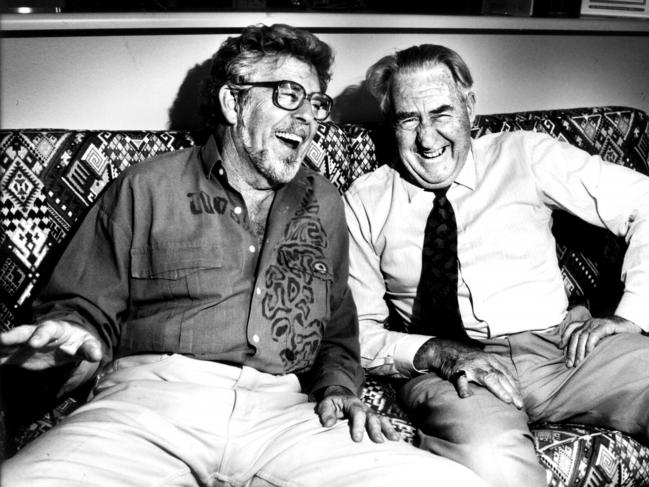

He continued to paint, with great speed. His 1973 portrait of Gough Whitlam, then prime minister, was painted in under two hours from a snapshot. Whitlam preferred it to the official, posed portrait by Clifton Pugh that hangs in Parliament House.

“I’m a workaholic,” Harris said in 1978. “I’m a terrible person, really.” This constant activity took its toll on his family life, though ultimately it was not as destructive as buying a Maltese nightclub.

“In that couple of years in Malta I probably lost all the money I earned up until that time. I virtually had to start again.” He would end up amassing more than $30m after his brother stepped in as his manager in 1981. “I think he’s a genius,” Bruce Harris said, “with some of the faults of genius, including a complete lack of financial understanding.”

Bruce took over just as Rolf’s career was fading. “I was doing too many charity shows and not enough paid gigs,” Rolf Harris said. “In the end the charity gigs started to dry up because I wasn’t on television enough for people to know who I was any more.”

The song that revived his career was as illogical as the song that had kickstarted his career in the first place.

Harris was one of several singers (ranging from John Paul Young to Kate Ceberano) to perform the Led Zeppelin ballad Stairway to Heaven in their own style, as a regular segment of the ABC TV show The Money or the Gun. His genial version, complete with wobbleboard, was released as a single in 1993. He appeared at the Glastonbury Festival that year (the first of three times) and released an album, Rolf Rules OK!, with his own interpretations of rock standards such as (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction and Smoke on the Water.

His inevitable return to TV happened the following year, hosting the popular magazine program Animal Hospital, which would run for a decade. It was followed by the high-rating Rolf on Art, in which he and other painters attempted to replicate the styles of the great artists of history.

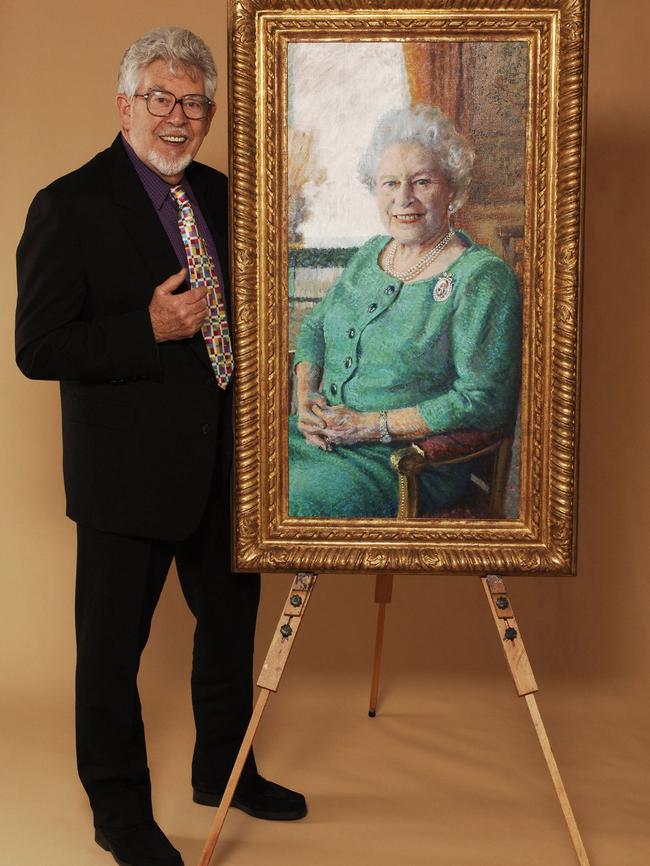

A national survey revealed that Harris was the best-known painter in Britain. In 2005 he was commissioned to paint a portrait of one of his fans, Queen Elizabeth (who had previously bestowed on him an MBE and an OBE). The event – as she sat, and he nervously tried to strike up a conversation – became a 2006 TV special. Today, the whereabouts of that royal painting is a mystery. Other paintings by Harris have been devalued to nought. He was stripped of his titles and the BBC removed his appearances on Top of the Pops.

Harris led a reclusive life at his home in Bray, on the Thames outside London, for the past few years after being released from jail, having served three years.

He died of neck cancer on May 10, but his death was confirmed only when a death certificate, indicating that he already had been cremated, was registered at the Windsor and Maidenhead local council on Tuesday (Wednesday AEST) .

“Rolf Harris recently died peacefully surrounded by family and friends and has now been laid to rest. They ask that you respect their privacy. No further comment will be made,” a short statement from his solicitor and family said.

The two-week silence after his death was yet another indicator of the depth of the performer’s fall from grace.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout