Economic recovery drives $50bn boost to budget

Josh Frydenberg will reveal a $50bn improvement in the budget bottom line for this financial year, economists predict.

The May 11 federal budget will reveal a $50bn improvement in the budget bottom line for this financial year, economists predict, as the Reserve Bank says the powerful post-COVID-19 rebound has already returned national GDP to its pre-pandemic level.

The extended boom in the iron ore price, which at above $US180 a tonne is well over triple the $US55 used in Treasury assumptions, and a labour market recovery that has defied all expectations will drive a dramatically smaller deficit than expected in the mid-year update only five months ago.

Commonwealth Bank head of Australian economics Gareth Aird said: “The fact that government finances are going to look a lot better than they thought does provide more wriggle room on the policy front.”

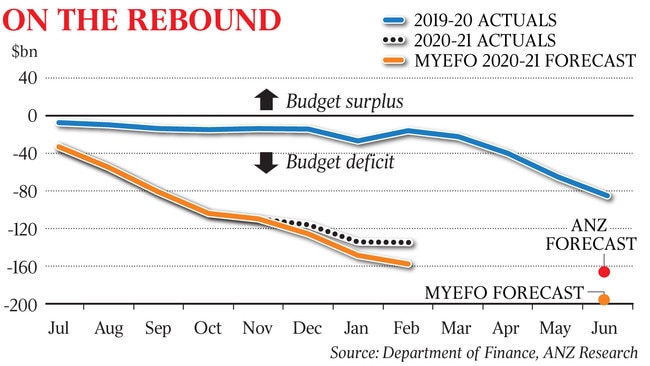

The Department of Finance has released numbers to February showing actual budget outcomes were $23bn better over the first eight months of the financial year, and analysts believe the eventual number will come in tens of billions better still.

Treasury’s December mid-year economic and financial outlook forecast a $198bn deficit in 2020-21, which would narrow to $109bn in 2021-22 before deficits of $84bn and $66bn in the following two financial years.

A survey of forecasts from Commonwealth Bank, ANZ, JP Morgan and Deutsche Bank reveal an average estimated deficit for this financial year will be projected at $150bn — an improvement of nearly $50bn in the space of just five months.

Mr Aird said he anticipated the projected deficit for 2020-21 would come in at $145bn, before dropping to $80bn in 2021-22 and eventually to $49bn in 2023-24. “They are still going to run big budget deficits, but they are going to be a lot smaller than the government will have expected.”

Deutsche Bank has released its own estimates for the deficit out four years, forecasting $150bn this financial year, $120bn next year, and then $90bn and $60bn.

NAB chief economist Alan Oster said he also expected a much improved deficit forecast in the May budget alongside an inevitable upgrade in Treasury’s economic estimates. But he said even a much improved outlook was not a precursor to balancing the budget, suggesting it would be 2030 at the earliest before the country was back in the black.

Mr Aird said the government had shown it was willing to run large deficits to support the economy, which widened the scope for additional support.

The government has already flagged it intends to do further additional targeted support to assist workers and businesses still feeling the impact of COVID-19 restrictions, as well as foreshadowing more aged-care funding, further investment in skills and training, and possible income tax relief.

Treasury has costed the $50 increase in the fortnightly JobSeeker rate at $9bn over the forward estimates, although Deloitte Access Economics partner Chris Richardson said the additional economic activity generated from the lift in the dole meant the actual hit to the budget would be more like a third of that.

“The best way to fix the budget is to grow the economy,” he said.

MYEFO forecast the unemployment rate would average 7.25 per cent in the three months to June 2021, but at 5.6 per cent in March, that number is likely to be significantly upgraded.

With hours worked and employment already back to where they were before the health crisis, tax revenue has poured in faster than expected. Lifting of restrictions and tens of billions in emergency government support drove the fastest six months of growth in history over the back half of last year. In April RBA meeting minutes, board members noted “the strong recovery in the economy had continued into 2021”.

Based on December quarter national accounts, real GDP would need to grow by 1.1 per cent for quarterly output to return to that of late 2019.

Economic activity may have returned to pre-pandemic levels much earlier than anticipated, but monetary policy-makers remained committed to keeping rates pinned to 0.1 per cent until 2024 “at the earliest”.

The unemployment rate, which was at 5.8 per cent when the board met and has since fallen to 5.6 per cent, was “still too high”.

The RBA board said wages growth would need to be “materially higher than it is currently” to drive inflation sustainably within the 2-3 per cent inflation target, and “this would require significant gains in employment and a return to a tight labour market”.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout